David Lebovitz gives you a crash course in film from an esoteric genre, director, or foreign country’s cinema, complete with spoiler-free descriptions and analyses of films that act as a good starting point for your own celluloid journey. This edition, in honor of Noirvember, he presents you with a look at the classic era of film noir.

Some hear the phrase “film noir” and think of a hard-boiled detective getting visited by a beautiful but sinister woman and tracking down a thief or killer. Others picture a relatively normal, maybe a bit down-on-his-luck individual goaded into a life of crime, likely through the allure of a femme fatale. Both of these definitions are correct, and variations of these two are the most common storylines found in noir.

To paraphrase Potter Stewart, noir is difficult to define but one knows it when one sees it. Elements common to most noirs include the femme fatale – dripping in sexuality but as dangerous as chupacabra – heavy use of shadows, cramped urban environments, complex plots, and a general lack of hope. The film was indicative of post-WWI America, where men were cynical from war and harboring resentment against women – in part for having the gall to leave the kitchen to take their civilian jobs.

While several prominent noirs were large and promoted, the vast majority of what we now consider noir were B movies – often produced by Poverty Row studios or as simple fillers for the second half of a double feature. This allowed them to get away with much more than would normally be seen in a feature film – while people who did anything illegal would always pay for it in the end, a lot of sexual references and other seedy implications were able to fly through without too much scrutiny.

Shoehorned endings were an unfortunate necessity of noir – the Hollywood Production Code forbade criminals from getting away with their crimes, which necessitated a lot of endings were characters get arrested or killed with minutes left in the film. This also led to some straight up bizarre conclusions, such as the… shall we say, “nuclear” ending to Kiss Me Deadly.

The term “film noir” was not invented – or at least not widely used – until after the end of the classic era. Most filmmakers at the time thought they were simply making melodramas.

The original run of film noir – often referred to as the “classic cycle” – started circa 1941 with films such as The Maltese Falcon and ended in 1958 with Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil. This article will touch on four films that provide a good introduction to the genre.

A companion article will be published in the coming days that will touch on neo-noir – noirs done since the classic cycle.

Detour (1945)

In terms of camerawork, sets, and almost anything tied to budget, Detour was a simple and straightforward film, but in terms of atmosphere, writing, acting, and unadulterated fatalism, it’s hard to find a purer example of noir.

The film follows Al, a nightclub piano player in New York. After Sue, his singer girlfriend, moves to Hollywood in search of fame, Al decides to follow. Lacking money, he hitchhikes across the country. On the way he gets picked up by Charles Haskell, a wealthy man who continually asks Al to give him some kind of pill or mint from the glove compartment. When it rains, Al – who is driving while Haskell sleeps – pulls over the convertible to put the top… only to have Haskell drop out of the passenger side door, dead. Realizing that the police would believe him to be his killer, Al takes on Haskell’s identity and drives the rest of the way to LA. On the way he picks up a female hitchhiker, who not only has a connection to Haskell, but turns out to be the most extreme example of a femme fatale.

Almost the entire film is told in flashbacks by Al, who is sitting alone in a roadside diner, recounting the events that led up to it.

Detour was shot on a shoestring budget from a Poverty Row studio and was filmed in six days. While it only got minimal notice when it was released, it was recognized as a seminal piece of cinema by the 1970s. Errol Morris has called Detour the greatest American film of all time. The film is in the public domain, so you don’t even have to seek it out on Netflix. You can watch it on archive.org for free to judge it for yourself.

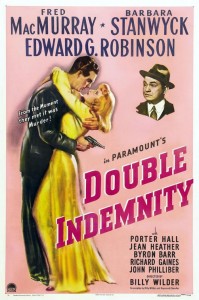

Double Indemnity (1944)

This is the film that set the standard for all future noir. Low lighting, a story with a morally corrupt protagonist, a femme fatale who reels him in, flashback narration, and Don Draper levels of alcohol consumption.

Insurance salesman Walter Neff meets Phyllis Dietrichson while visiting her house to remind her husband that his auto insurance is up for renewal. Walter and Phyllis flirt until Phyllis asks if she can take out life insurance on her husband without him knowing. Walter realizes this part of a plan to murder her husband and he initially wants no part of it – but changes his tune later when he can’t stop thinking about her. Knowing the ins and outs of the insurance industry, Walter concocts a plan to murder her husband, make it look like an accident, and trigger the double indemnity clause – resulting in payoff of twice the policy’s worth. The main thing standing in his way is his friend and co-worker Barton Keyes – an intuitive and clever claims adjuster – who has his suspicious that something fishy is happening with Mrs. Dietrichson’s claim.

The entire story is framed as Walter confessing into a Dictaphone. In prototypical noir fashion, you sympathize with the main character and don’t want him caught – despite the fact that he is committing a murder and adultery.

The film was directed by the always great Billy Wilder and written by Wilder and Ray Chandler. The film features a cameo by Chandler, which is the only known footage of him known to exist.

That’s Chandler in the back, Hitchcocking it up.

Chandler and Wilder worked together with the civility of betta fish, but the end result is this film – a big hit in its time, appreciated more in retrospect, and the standard bearer for all noir following it.

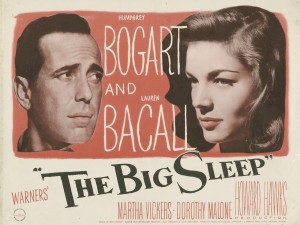

The Big Sleep (1946)

The Big Sleep is a prime example of how ridiculously complex noir plots could get. Roger Ebert described the film as “about the process of a criminal investigation, not its results” – and that’s about as apt description as you’re going to find. This film features blackmail, murder, and romantic entanglements. It’s also one of the many “Bogie and Bacall” pictures – old Hollywood’s biggest power couple. More than anything else, it’s one of the definitive private eye stories of the era – perhaps even in Hollywood history.

The film stars Humphrey Bogart as one of noir’s mainstays – Detective Philip Marlowe, the wisecracking, heavy drinking, ladies’ man private eye that every other private eye in film history aspires to be. Marlowe gets called to the home of General Sternwood, an aging wheelchair-bound veteran. Marlowe is asked to help resolve gambling debts by Carmen, Sternwood’s younger daughter, to a bookseller named Geiger. On the way out, Marlowe is stopped by Vivian (Lauren Bacall), Sternwood’s oldest daughter. She suspects that her father’s actual motive is to find Sean, a young friend of his who vanished a month prior. A small amount of investigating uncovers a blackmail scheme, a front company for an illegal operation, and some uncomfortable truths about the Sternwood family.

It’s hard to describe more due to its complexity, but it’s a prime example of the convoluted plots and shady characters common to noir. (It’s also one of the inspirations for The Big Lebowski.)

Gun Crazy (1950)

No, this is not a biography of Wayne Lapierre. It’s a story about choices.

The script was written by Dalton Trumbo, although it is credited to another screenwriter because Trumbo was blacklisted at the time. This film predates the film Bonnie and Clyde but it’s hard not to compare, since it’s about a sharpshooting couple on a crime spree. The femme fatale in here is about as close to the literal meaning of that name as you can get – she doesn’t even try to hide the fact that she’s crooked.

Ever since he was young, Bart Tare had an obsession with guns. He was a crack shot who never missed, but could never bring himself to kill any living creature – human or animal. At the start of the film, at age 14, he steals a gun from a store and is sentenced to reform school. After straightening up at reform school and a stint in the army as a marksmanship instructor, Bart returns home. His friends take him to a traveling carnival, where he meets and becomes instantly smitten with Annie Laurie Starr, the carnival’s beautiful sharpshooter. The two elope together, but Laurie gets greedy and demands they started using their shooting skills to enter a life of crime. Against his better judgment and morals, the hopelessly-in-love Bart teams up with Laurie to go on a string of cross-country robberies – even though he never harms anyone. The question is, how long can they – Bart in particular – keep on living like this?

A common theme in many noirs is choice – each person chooses their own destiny. In noirs, people choose poorly, but at the end of the day, it was usually their choice and their choice alone. In that sense, Gun Crazy is among the more existential noirs – everything that happens to Bart is a result of his choices.

Pay attention to the courtroom scene at the beginning – that’s a young Russ “Riff from West Side Story” Tamblyn playing 14-year-old Bart. (I prefer to think of him as Russ “Dr. Jacoby” Tamblyn.)

All the films listed here are available on Netflix, or are public domain and can be streamed online for free.

2 thoughts on “An Introduction to Film Noir”