Nobody’s perfect. Sometimes the only way to understand why you love an artist is to examine something they’ve made that just doesn’t work. Sometimes, you have to Kill Your Heroes.

Like many Jersey boys, I was raised on The Boss. Bruce Springsteen is an American icon known the world over, but to those of us who hail from his home state, he’ll always belong to us first. Bruce (yes, we all call him “Bruce”) means different things to different people, but to most he represents the ideal of a hard-working guy who started with nothing and made it big but still remembers where he came from. He’s an escape fantasy for anyone who ever dreamed of speeding away from their hometown and the mundane future it represents, but he’s also a symbol of pride in a hard day’s work. If you listen to the Springsteen catalog as a whole, the overall message seems to be: “You don’t have to work at the steel mill if you don’t want to, but if that is what you wanna do, you don’t have to feel like shit about it.”

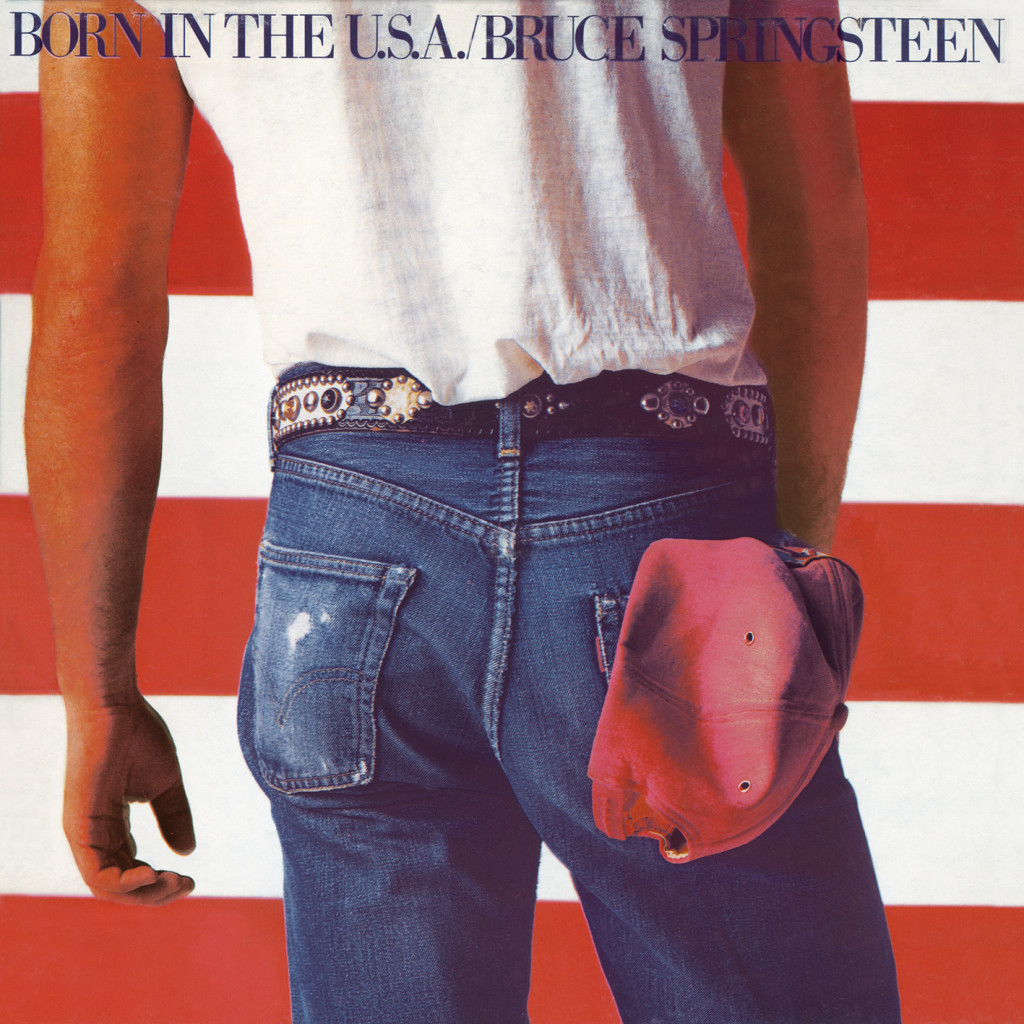

While Bruce Springsteen has had a number of successful albums and singles (such as the cinesonic masterpiece Born to Run), to the average pop music listener his best known work is the 1984 LP Born in the U.S.A., which included the hit singles “Dancing in the Dark,” “I’m On Fire,” “Glory Days,” and of course, “Born in the U.S.A.” itself. While many of these songs remain staples of classic rock radio even today (the album celebrated its 30th birthday this month), it may surprise some of you readers when I tell you that these tracks, and the album as a whole, are extremely divisive among Springsteen devotees. As an example of the kind of lifelong fan who will have long discussions debating the relative quality of two different nigh-identical live renditions of “Prove It All Night,” I can sum up my feelings about Born in the U.S.A. pretty succinctly. Born in the U.S.A. is unsatisfying because it’s largely devoid of the qualities that make Bruce Springsteen’s music great: passion & storytelling.

One of the reasons Bruce Springsteen has remained such an enduring performer and songwriter is that, while his catalog ranges from loud, vigorous stadium rock to subdued, haunting folk, he puts his back into all of it. Fans often describe his songs as feeling like short films, of conveying firm images with emotional resonance. Some Bruce songs are complete stories with a beginning, middle, and end, while others are more like soliloquies in a larger, lifelong tale. Some of these stories are triumphant and joyful, and others are somber and heartbreaking. Their intent is usually very clear and specific, but the characters are also people you recognize from your own life–maybe they’re you. Whether it’s an electrified rock anthem or a cool and quiet folk ballad, Bruce, at his best, is always in character, completely engrossed in the emotion of the role.

Allow me to present two, completely different examples of The Boss’s commitment to selling the story of the song:

First, off of 1978’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, here’s “The Promised Land,” which may be the quintessential Bruce Springsteen rock song. In “The Promised Land,” Springsteen’s character is down on his luck, exhausted from the unrewarding job he’s inherited by birth. He’s surrounded by desert and emptiness. He works hard and he gets by, but he’s got nothing to call his own. And one day soon, goddammit, he’s gettin’ out of there. He’s gonna ride out of that desert and make something of himself. “Mister, I ain’t a boy, no, I’m a man, and I believe in a Promised Land.” It’s a song about faith in oneself, in having the courage to reject what’s been handed to you and fight for something better. As the song builds, we can feel Bruce’s character losing patience, making ready his escape. No matter the danger, he’s “headed straight into the storm.” Even if he doesn’t make it, this moment, the one in which this song takes place, is a victory for independence. The song is powerful enough on paper but The Boss’s performance, from his vocal to his harmonica to his guitar solo, completely sells the song’s fairly complex emotional baggage. It’s a highway drive to an empty horizon that you must choose to believe will grant you salvation.

(If somehow the album version doesn’t make you feel like a million bucks, try this live version from 1978.)

Seventeen years later in 1995, Springsteen released a folk album, The Ghost of Tom Joad. While this album abandoned the rambunctious rock sound of his youth in favor of acoustic guitar, harmonica, and atmospheric synthesizers, the result was no less compelling. On the album’s lead track, Bruce expands on Tom Joad’s famous speech from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, telling the story of a man (or rather, all men) who live in soul-crushing poverty in a country that prides itself on prosperity and opportunity. Like “The Promised Land,” it’s not a complete story, just a vignette, but there’s enough detail in the song that your subconscious can fill the rest of the gaps, like a dream. While he never raises his voice above a stage whisper, Bruce still sells the desperation in his delivery of the lyrics, and in the haunting wail of his harmonica. Like many of his songs and albums, The Ghost of Tom Joad is overtly political and strongly socialist, even earning the approval and admiration of Rage Against the Machine guitarist and far-left activist Tom Morello, who’s since joined Bruce’s E Street Band on tour and in the studio.

Born in the U.S.A. seems to have initially aimed for this kind of passion and profundity, but piece by piece abandoned it in favor of popular success. The seeds for this album were first sown during production of his previous effort, the bare and powerfully depressing solo album Nebraska. Nebraska was a dour-but-affecting series of tragedies, chronicling small town people succumbing to despair and criminality. (It was not one of Springsteen’s more commercially successful albums.) It was during these sessions that The Boss recorded the initial version of the song “Born in the U.S.A.,” originally entitled “Vietnam,” which was finally released as part of the archival collection Tracks in 1998.

This original version, while admittedly less exciting than the version that would later lead off the album and become a radio hit, is very unlikely to be mistaken for a jingoistic anthem, which is exactly what happened to the version that got released.

“Born in the U.S.A.” tells the story of a young man who, after some trouble with the law, ends up serving and suffering in the Vietnam War, only to come home to a country that can’t offer him work or respect. It is critical both of the United States government for sending people to fight in a pointless war, and of the US citizens who punished returning veterans for fighting in a war they never chose to fight. “I was Born in the U.S.A.,” repeats Bruce’s narrator, with the sarcastic bite that implies the next line should be “and look at all the good it did me.” It is in praise of no one.

I would never argue that the Nebraska version of the song “Born in the U.S.A.” is more powerful or effective than the one released to the public on the eponymous album, and despite the enormous percentage of people who misinterpreted the song as an affirmation of their nation’s exceptionalism, surely a larger number of listeners heard the song and got the message than would ever have listened to the dour acoustic version if that had been released instead. Performed with spit, bile, and complete commitment to a story, the single “Born in the U.S.A.” represents the passion that makes Springsteen compelling, and as such is one of the only songs on the album that is worthy of its stellar reputation. However, its success is built on compromise, on a race toward the musical middle, one that becomes more and more obvious the deeper into the album you look.

Born in the U.S.A. is already losing its way on the second track, “Cover Me.” At first, it seems as if he’s still carrying the Vietnam thread from the previous song, reappropriating a military term for suppressing fire as a metaphor for sex. The song, while written by Springsteen, was originally meant for Donna Summer to perform, so the wartime connection may be coincidental, but its placement on the album right after “Born in the U.S.A.” makes this hard to accept.

Promise me baby you won’t let them find us

Hold me in your arms, let’s let our love blind us

Cover me, shut the door and cover me

Well I’m looking for a lover who will come on in and cover me

There are a number of ways to read the lyrics–for instance, if this song were written for Nebraska I would assume the speaker were a returned veteran with PTSD begging for a little love and support in the only language he can remember–but none of them seem to support the track’s dance beat. (It even had a dancier remix.) It’s as if the song was written with a deeper theme in mind, but then it was abandoned in favor of keeping the track from getting too dark for pop radio. While the song “Born in the U.S.A.” had a narrative that clarified the emotional dissonance of the music, “Cover Me” has none, leaving me wondering what he’s trying to accomplish before ultimately answering “nothing – it’s just a song.”

While the canon of pop music is full of tracks that satisfy despite having no any story, depth, or meaning, this is not something Bruce Springsteen is particularly good at. His attempts to write simple, easily digestible pop songs usually result in his worst work. This is why Born in the U.S.A. doesn’t hold up. Bruce is deliberately holding back from using all of his skills, watering down his work to please others instead of doing what he’s good at and trusting the audience to appreciate his work, as they did with Born to Run. What he ended up with was an album littered with nothing songs.

Take “Darlington County,” an upbeat country-rock song that’s exceedingly simple, just a fun song to groove to at the bar. There’s a story in the lyrics like always, but it’s a boring story that mostly amounts to “Hey girl, you’re so darn pretty.” The problem is that the song doesn’t have the necessary hook or drive to stay in your head after you’re done listening to it. There’s no commitment, no drama, and no earworm factor. It’s a saltine cracker. “Downbound Train,” on the other hand, is so melodramatic that emotional investment is impossible. While it’s supposed to feel tragic and heartbreaking, the story is completely weightless, and it’s performed like Springsteen has no interest in expressing anything at all. “Downbound Train” talks down to the listener, telling you to be sad instead of actually making you feel sad.

More frustrating than a simple song that’s forgettable is a song that could be compelling if the songwriter didn’t hold back. Again, there’s nothing wrong with having a song that’s just for entertainment. Not everything needs to be high art. The problem is that many of the songs on Born in the U.S.A. feel like they were meant to be something more, but then got hollowed out for commercial purposes.

“Working on the Highway” is another holdover from the Nebraska sessions that got turned into a pop song for this album. It’s the story of a bored man who runs off with an underage girl, gets arrested, convicted of what I assume is statutory rape, and sentenced to work on a chain gang on I-95, right where he started. The thing is, the song is relentlessly cheerful sounding, never losing its rockabilly bounce and repetitive organ hook. If you’re not paying very close attention to the rapid-fire lyrics, you’d completely miss the song’s creepy story. It’s played off as fun–a playful tale in the style of “I Fought the Law (and the Law Won).” I suspect that the Nebraska version wouldn’t have tried to wallpaper over the song’s eerieness; its original title was “Child Bride.”

Most maddening of all is “Glory Days,” an inescapable bar rocker in which a boring non-story is sung over an endless and irritating organ line. In “Glory Days” a man tells the story of how he sits at a bar, “[has] a few drinks,” and recounts old stories with people he knew in high school about how they used to be cool. Their lives clearly suck now and the past is all they have. “I hope when I get old I don’t sit around thinking about it,” sings Bruce, “but I probably will.” This is, and I’m counting it among songs in which characters are brutally murdered, the most depressing Bruce song ever. The characters in “Glory Days” have all totally given up, their best days behind them, the rest of their nights to be spent drinking at this same bar telling the same stories back and forth until they die. And the music is so skull-splittingly cheerful that people sing along to it, as if to say: “Yup, me too, woo hoo!”

Springsteen songs, at their best, are about being somebody, whether that means being a rock star, or a better dad than your father was, or the best street racer in the Northeast. There’s a reason Bruce is so often associated with the mythical American Dream. His characters fight for a better life for themselves and their families, by running out of dead end towns for the big city, by braving the deadly Rio Grande crossing, by being an outlaw, or by being just an honest, hard working person who takes pride in their sweat. “Glory Days” is about being nobody. They’re done. They give up. This song is played at parties.

“Glory Days” can be interpreted in one of two ways, and either way exemplifies everything that’s wrong with Born in the U.S.A. as an album. The first interpretation is that, despite the handful of pretty grim images in the lyrics (“She says when she feels like crying \ she starts laughing thinking about \ Glory Days”) that the song is supposed to be light and wistful, that the message is that, even when your life doesn’t turn out like you dreamed, you should be happy that you still have fond memories you can look back on. This definitely has some value, but sort of sells out the “talk about a dream, try to make it real” thesis of Springsteen. The second interpretation is that Springsteen took a song that was supposed to be about failure and misery and dressed it up as fun in order to sell records. Consider this verse that got cut from the final version of the song:

My old man worked 20 years on the line

and they let him go

Now everywhere he goes out looking for work

they just tell him that he’s too old

I was 9 nine years old and he was working at the

Metuchen Ford plant assembly line

Now he just sits on a stool down at the Legion hall

but I can tell what’s on his mind

No baseball park organ is going to make that not sound like hell.

It’s not selling out to go from making meaningful art to commercial entertainment. You can argue this is what Bruce Springsteen did with his most successful single off Born in the U.S.A., “Dancing in the Dark,” which is a perfectly satisfactory pop song of its day, and was written very specifically for that purpose. That’s not a sin, everybody’s gotta eat. It is selling out to undercut the meaning of your art in order to package it as commercial entertainment. That’s essentially what Born in the U.S.A. is as an album: a series of songs written with deep themes in mind where the themes are buried underneath layers of production and sandwiched between fluff in the hope that they’ll be ignored by the average listener, lest they be offended by them.

Because I don’t like to be such a downer, and because I love Bruce Springsteen, I’ll leave you with the one song on the album that I think is fantastic:

“No Surrender” utilizes all the strengths of Springsteen’s toolbox. It’s the story of two childhood friends bound together by the power of music. While they may be older now, one of them hasn’t given up on rock ‘n roll. The chorus is a plea to his old companion to remember that they once believed they could “cut someplace of [their] own with this drums and these guitars” and that maybe they still can. There are vivid details (“I’m ready to grow young again and hear your sister’s voice call us across open yards”) that genuinely recall the feeling of being a kid. The story doesn’t promise a happy ending, it offers one: you, the listener, must take on the role of the singer’s childhood friend and decide whether or not to believe in the music.

Now that’s a Bruce Springsteen song.