Continuity is one of main driving forces behind Big Two comics today. It’s a way to tell bigger stories, to feel like a more fleshed-out universe, and, let’s be real, to sell more books. DC Rebirth is an event that’s about continuity within the actual text, while Marvel continues to pride itself on avoiding drastic, universe-wide resets, building instead on lines all the way back to characters’ first appearances. With the rise of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a focus on continuity has been pushed even further, with film adaptations of old stories feeding into the development of new ones.

It’s surprising, then, that Civil War II, by Brian Michael Bendis, David Marquez, Justin Ponsor and Clayton Cowles, reads very well as a standalone story, and considerably less well as you take into account the history and continuity of these characters, both in comics and on film. CWII #1 deals with the discovery of a newly-empowered Inhuman named Ulysses whose ability to predict the future provides an ethically-questionable edge to the Marvel superhero community. Captain Marvel is of the opinion that Ulysses’ gift should be used proactively, preventing crises and minimizing casualties. Iron Man worries about the questions of reliability and free will in trusting this new, unpredictable source for the world’s peace and justice. Most other characters line up with one or the other, with varying degrees of passion.

As an issue, it’s well-written, with a focus on small moments between battles that hasn’t been seen in event comics for a while. The dynamics between the leads feel real, even if their stances are a little broad. If this was your first event comic, and you were armed with a passing familiarity with the characters from Wikipedia etc., you’d probably like it a lot, and you wouldn’t be wrong. The problem is that the sheer amount of history, even within the past decade or so, that follows these comics around means they all sort of sound like idiots.

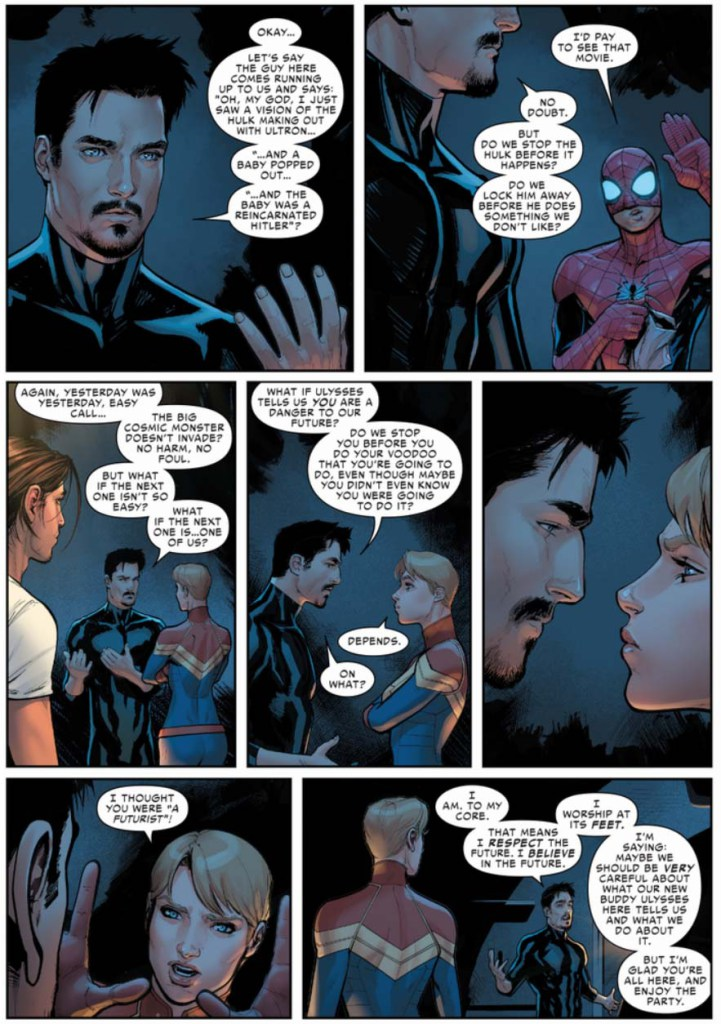

The decades of stories behind the Marvel universe are sort of like the saying about infinite monkeys and infinite typewriters. It’s getting increasingly difficult to come up with a conflict that doesn’t bear at least passing similarities to a previous book. So all these lofty arguments about “what if one of us was a threat, what would we do” begin to fall apart in that context. When Tony Stark comes up with a snarky hypothetical about Hulk and Ultron making a baby Hitler, it’s hard to ignore that back in 2006, Hulk was viewed as a future threat, and a group of Marvel heroes, Stark himself among them, sent him into space, kicking off the Planet Hulk and World War Hulk events, in which their decision turned into a big problem. The past decade alone is rife with characters turning against each other in the name of what they thought was right, from Avengers vs. X-Men to the “Time Runs Out” arc in Hickman’s Avengers to Avengers Standoff, an event that ended mere weeks ago. The idea of divided loyalties isn’t a hypothetical, it’s something that happens three times a year.

This also leads to a larger problem: superhero comics are crazy. At any given point, one or more marquee character is probably brainwashed or possessed or replaced by a clone. Wolverine spent a period as a mind-controlled Hand assassin. Spider-Man spent 18 months real-time possessed by the mind of Doctor Octopus. At this very moment (in-story), Steve Rogers may or may not be a sleeper agent from HYDRA, depending on how that story in his own book plays out. Nearly every character involved was either replaced by a Skrull spy in Secret Invasion or had been suspected of it. In the real world, intelligence issues around pre-emptive strikes are thorny, and films like Eye in the Sky and A Most Wanted Man illustrate the complicated and compromised ethics involved. In the Marvel universe, where aliens invade and destroy cities on a regular basis, it feels pretty simple. For the metaphors to hold at all, the characters need to ignore both their history and the realities of the world they live in.

Other plot beats less philosophical are still affected by this long-term view. SPOILERS FOLLOW. At the end of the issue, it’s revealed that War Machine was killed in a pre-emptive attack on Thanos, one which succeeded, but at the cost of his and possibly others’ lives. It’s a devastating moment, as Captain Marvel holds his body and cries out for help in a way reminiscent of Crisis on Infinite Earths. The problem is, this is comics, and death is never permanent. Marquez’s panel of Thanos blowing a hole through War Machine’s body is artfully done, but unfortunately reminiscent of last year’s summer event, Secret Wars, in which numerous major characters met ignominious deaths that were played for laughs. The point there was that Secret Wars was a story about comics stories and no deaths were gonna last, but that fact is still true here, even if the story isn’t going to acknowledge it. James Rhodes has died before, and if I’m not mistaken, is already on his second clone body. He’ll be fine.

I know I just spent about five hundred words discussing problems with this story, but believe it or not, I actually enjoyed it quite a bit, and I’m looking forward to the next one. The focus on interpersonal relationships as the primary driver of the conflict is a nice change from stories about strange aliens or beings looking for MacGuffins, and the prioritization of quiet conversations over loud fights is refreshing. The Celestial fight in the beginning is humorously glossed over in a way that such things must appear to some of the heroes involved, and a similar “tell, don’t show” approach to the Thanos fight drives home the tragedy of it for the characters who weren’t there. It’s written from the overarching mechanical perspective of later Hickman, but from a flawed, human view. The key to this book is that you have to take it on its own terms. Civil War II takes place in the Marvel universe, but a simplified, keyhole version of it. For the purposes of this story, the Illuminati, time travel, Dark Reign and even the dissuasive carnage and fallout of the original Civil War are irrelevant enough that they may as well be forgotten. The characters are all here, and they behave in ways that are both consistent internally and to their classical depictions, but no one is gonna say “Remember when Scarlet Witch killed half of us? Sure would’ve been nice to have a heads up on that.”

Honestly, in this way it isn’t too different from other Marvel events. As I’ve said, all stories at this point are going to be reminiscent of something, and a general lack of barriers to entry is probably intentional and the kind of thing people have been crying out for. Jason Aaron’s Original Sin event (which I loved) opens with Dum Dum Dugan revealed to have been a robot duplicate for decades, and absurd, impossible retcons like that flow freely from then on. By comparison, a book shrugging off old continuity in favor of a stab at real-world relevancy is pretty tame. “Don’t reopen old wounds,” the book seems to ask of us, “and in exchange you’ll get the grounded debates about superhero ethics that the Twittersphere is always clamoring for.” So far, I like the results enough to consider it a more than fair bargain. At least until next month, when I’m sure the punches and explosions will really kick off.