Even among the 40-something albums that Prince Rogers Nelson released between 1978 and 2015, there is still so much to uncover. The weeks since his passing have led to a lot of discovery and rediscovery, with even the most faithful uncovering handfuls of tunes from relative obscurity.

However, since that fateful April day—and even during the near two decades since it was released—there is one record I have found particularly intriguing among his catalog, which has strangely not attracted much heat from even the most faithful followers. It’s a drastic departure for Prince in terms of sonic landscape and lyrical honesty, and, like far too many of his works during his unpredictable “nameless” period from 1993 to 2000, it fell into obscurity partially by its own design. But in assessing the brilliant highs and tragic lows of Prince now that he isn’t here to tell his story his way, I find this tale very much worth telling.

This is the story of Prince telling The Truth.

It’s easy to forget—it has been even before he died—that for most of the 1990s, Prince was seen by many as a has-been. His mainstream fanbase had slowly dwindled for a decade, after subsequent, nonetheless brilliant albums failed to catch on quite like his juggernaut Purple Rain in 1984. He kicked off the 1990s with the abysmal film Graffiti Bridge, and followed that up with the formation of The New Power Generation, a partially rap-inspired band that critics saw as the move of a musician following trends, not setting them. Then, on his birthday in 1993, there was the bizarre proclamation that he would change his name to an unpronounceable symbol, an act of protest against his label, Warner Bros. Records. Talk show hosts, tabloids and even fans had wondered if he’d finally lost it.

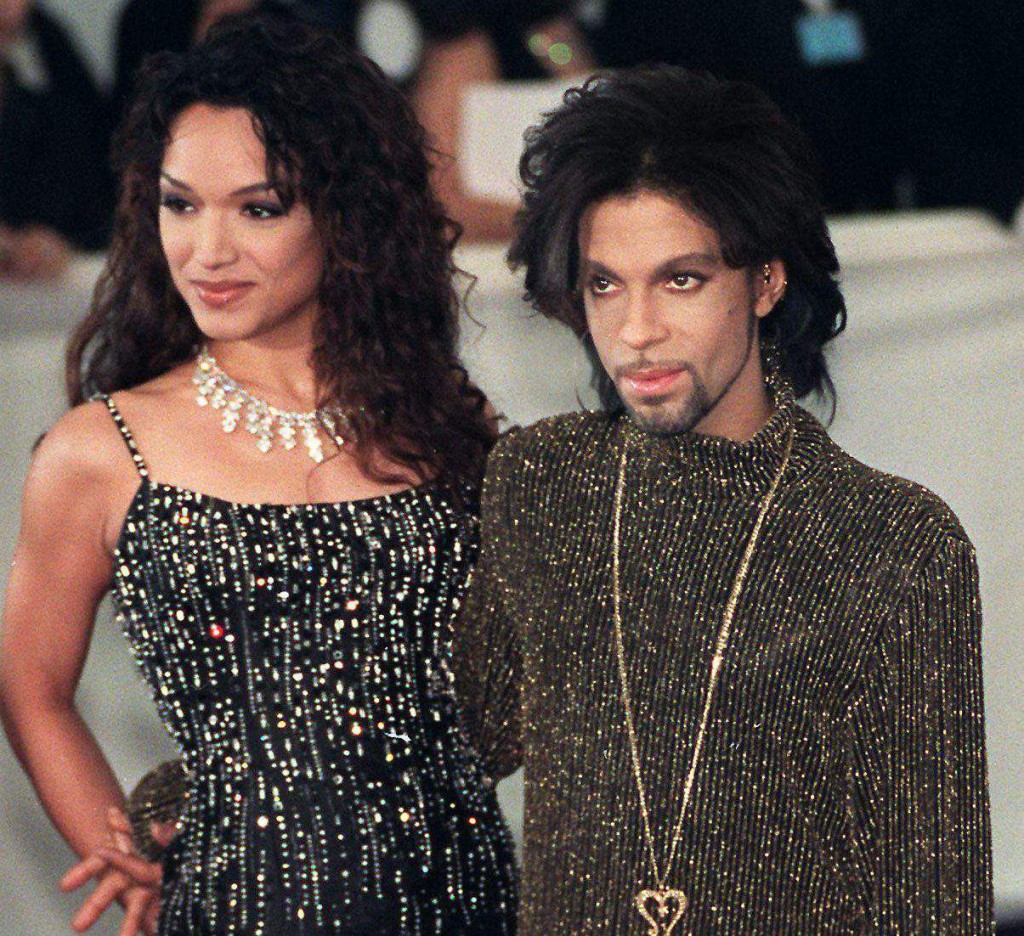

What many were missing at the time was the music. Negotiating out of his Warner contract, a slow, painful process, nonetheless liberated him in many ways. The fall of 1996 saw his first release outside of his original record deal, a sprawling triple-album called Emancipation, which found him much freer and laid-back. Those sentiments extended past his music, too. On Valentine’s Day 1996, Prince married dancer Mayte Garcia, and the couple announced they were expecting a child shortly thereafter. Prince was elated, reportedly turning free space in his Paisley Park recording complex into a play area and included the child’s sonogram as part of the rhythm track on Emancipation’s “Sex in the Summer.”

But tragedy struck just as Emancipation arrived in stores. The child was born with Pfeiffer syndrome, a rare disease that causes premature fusion of bones in the skull; within a week, the couple reluctantly took the child off of life support. While Prince contradicted the subsequent media reports, going so far as to say, “It’s all good,” during an interview with Oprah Winfrey that November, he was privately crushed. A previous attempt to conceive with Mayte resulted in miscarriage, and his dream of fatherhood was a goal that not even multiplatinum albums could help realize. (The setbacks also contributed to the eventual annulment of their marriage in 2000.)

And so, sequestered yet again from the world in Paisley Park, The Artist started recording and reflecting on his loss and his life. For reasons never explained, he started recording this batch of songs almost entirely on an acoustic guitar, something he himself had almost never done. (Bassist Rhonda Smith added a few parts to some songs, as did percussionist Kirk Johnson, a frequent collaborator with The Artist at the time.)

The tunes were all over the place, and nothing easily recalled his last two decades of recording. “Circle of Amour” was a light tale of a group of high school girls and their shared sexual awakening. “One of Your Tears” was a wounded plea to an ex-lover. “Animal Kingdom” was an ode to vegetarianism, with Prince pledging to “eat no red meat or white fish / or funky, funky bleu cheese,” while “The Other Side of the Pillow” and the title track dabbled in straightforward 12-bar blues—a rootsy, gutsy move for anyone, not just a former pop star approaching 40.

Having fallen in love with Prince’s imperial phase some 20 years after the fact, devouring many of the Warner-era albums from high school to college, it was The Truth that got me to stop subscribing to the narrative that, once The Love Symbol replaced the name, he started to suck. It seemed like Prince could do anything, I’d thought, why shouldn’t he? The Truth doesn’t have the kind of guitar heroics that drew me deeper into his web, but it was still showy, with an air of “Can you believe I’m still doing this, people?”

But then Prince delved into unexpectedly serious territory at several points on the album. Two tracks in, “Don’t Play Me” offers one of the clearest pictures into The Artist’s mind at the time—a stark letting down of his guard that not even his contemporaries Michael Jackson or Madonna could entirely commit to—and may be one of the best Prince tracks you’ve never heard.

“Don’t play me,” Prince softly begs the listener, ostracizing himself over and over for a multitude of reasons: being over 30, being drug-free, being “the wrong color” and playing guitar. “My only competition is…well, me, in the past,” he bemoans. “I’ve been 2 the mountaintop and it ain’t what U say.”

Never before had Prince been this soul-baring. Years later, I’d read about his legendary track “Wally,” recorded in 1986 and boldly tackling his breakup with collaborator Susannah Melvoin before being erased by Prince himself. But I can’t imagine “Wally” sounds as straight-up alone as “Don’t Play Me.” This is a Prince with few kingdoms left to conquer, going on (and going on well) because, whether you care or not, this is what he needs to do.

But if you thought that was honest, it was a fable compared to penultimate track “Comeback.” Over just two minutes, The Artist crafts a vocally dense tribute to fallen friends—and it’s not too hard to imagine he’s talking about the child he never got to see grow up. “Spirits come and spirits go / some stick around for the aftershow,” he sings. “Don’t have 2 say I miss you / ‘Cause I think U already know / If you ever lose someone dear 2 U / Never say the words ‘they’re gone’ / They’ll come back.”

“Comeback” was a song I’d known well enough when becoming a young Prince fan. But when I got that terrible, terrible news that an artist who’d shaped a fair amount of my post-high school taste and temperament had suddenly died, it was these lyrics—not “Purple Rain,” not “Sometimes It Snows in April”—that I went back to.

In his own special way, he provided the blueprint for my grieving process, a process that still continues to this day, the first birthday he’s not around for. In the words of “Comeback,” I think of a legend who’s not here, corporeally, but whose sounds will fill my ears (and, likely, that of my heirs, and their heirs afterward) for years to come.

By the album’s final song, “Welcome 2 The Dawn” (a gorgeous tune that recalls the scope of “Purple Rain” and “Gold,” two of his best album closers), it’s hard to imagine how, even taking Prince’s symbol-era status into account, a record as honest and refreshing as The Truth gets overlooked. And then you consider how the album was actually released.

Prince was, perhaps rightly, fed up with the traditional business model of selling music. He wasn’t interested in major labels’ numbers games, but was interested in circumventing the traditional channels as early as 1994, when he started a hotline to buy his works, 1-800-NEW-FUNK. As the Internet started to take hold of popular culture in the mid-‘90s, Prince wisely saw the potential of the Web as a new way to distribute music even before the MP3 was common knowledge. It was online that The Truth first became known, quickly announced on Prince’s website Love4oneanother as the follow-up to Emancipation for 1997.

Then, as he so often did, Prince switched gears. The Artist soon announced the release of Crystal Ball, a triple-disc, career-spanning set of tracks from his fabled vault (named after a 1986 triple album that was pared down and released as the sublime Sign “O” the Times a year later).

What happened next was a series of blunders that perhaps proved Prince far more adept at art than commerce: after only guaranteeing manufacturing after 100,000 phone orders were placed, manufacturing delays beset the project. And while people started receiving their copies in early 1998, Prince irked faithful fans by allowing Best Buy to carry a four-disc set of Crystal Ball and The Truth, beating many direct order deliveries and coming with actual album art and packaging (the delayed “innovative packaging” for fan club orders required fans to print out liner notes available online).

It was these kinds of business blunders that would keep Prince mostly in the wilderness until his major comeback in 2004 with Musicology—and, in turn, keep The Truth from being heard by many past the most faithful fans. But even he knew its importance in his canon: when granting exclusive streaming access of his catalog to TIDAL in 2015, The Truth was broken out alongside Crystal Ball, free to be considered anew.

Indeed, never say the music is gone—it’ll come back. And since we’re sadly living in a world where Prince can’t keep gifting us with his amazing musical talents, it’s lost classics like The Truth that will set us free.

Welcome 2 The Dawn.