Diversity and representation have long been a serious issue in the film industry, and 12 Years A Slave winning some Oscars hasn’t exactly changed that. Outside of that prestigious anomaly, people rarely imagine black film to be much more than gangster movies, cookout comedies, and Tyler Perry. Our very own Dominic Griffin will prove otherwise, shedding a light on unsung, underrated, forgotten and new films that show the breadth and versatility of the black voice in film. Named after one of Billy Dee Williams’ affectionate nicknames, this is Dark Gable Presents…

We’ve written extensively about The Purple One’s most iconic piece of cinema in the past, but we’ve never truly explored Prince’s work as an auteur. Purple Rain, despite its flaws, displays a strong distillation of Prince’s sonic identity, but he didn’t direct it. Prince was a versatile musician, deft with any instrument he deigned to play, so the idea of an artist of his caliber at the helm behind a camera should be cause for salivating. Given hindsight, we know he wasn’t quite as gifted with the silver screen as he was with, say, a guitar. But it’s still thrilling to revisit his experimental excursions into the world of the projected image.

Prince’s three directorial credits offer canted looks at the legend’s vision at its most charming, most confounding and most pure.

Under The Cherry Moon is probably the most curious of these films. Released in 1986, it’s hard to imagine a more direct 180 from Purple Rain than this beguiling, Parisian romantic comedy. Prince stars, scores and directs from a thin but lovable Becky Johnston script that’s short on substance but long on brio. Prince plays a gigolo named Christopher who cons desperate, older women alongside his brother Tricky (Jerome Benton, displaying amazing chemistry with Prince). The duplicitous pair set their sights on Mary Sharon (Kristin Scott Thomas), an heiress soon to be worth $50 million. There’s not much more to the narrative than the obligatory love story that blossoms between Christopher and Mary, yet there’s seldom a dull frame.

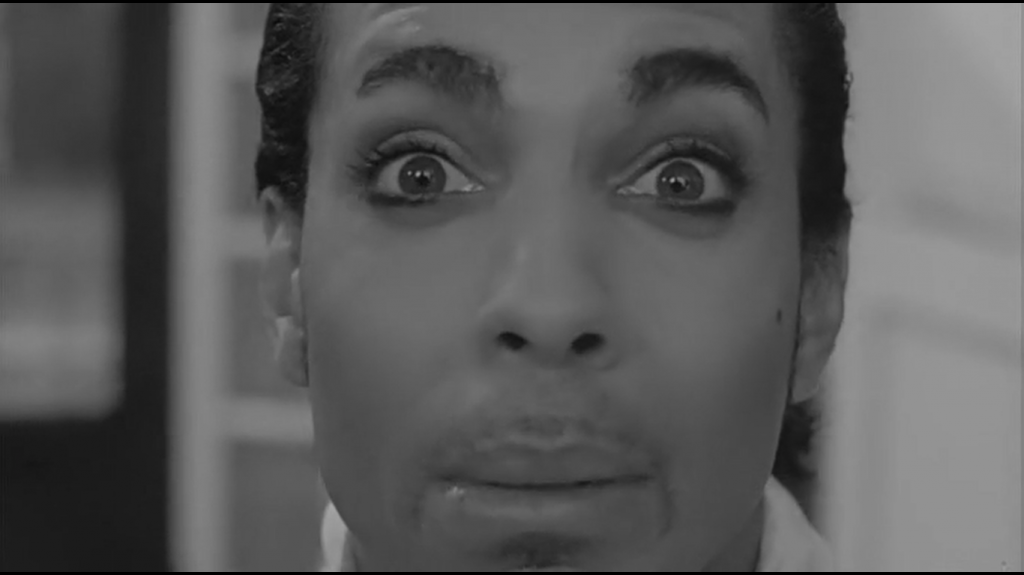

Prince’s unique flair is on display in everything from the wardrobe choices to the tonal whiplash of chaste, slapstick-y comedy metamorphosing into unmistakably erotic flourishes, but the photography sets the film a cut above. Michael Baullhaus served as the cinematographer, filling the screen with this indelible black and white portraiture and rooting the otherwise unorthodox exercise in a classical setting that implies taste and restraint, even while the writing and editing threaten to ride off the rails. At times, you would be forgiven for questioning some of the creative decisions driving this movie forward, but it’s lit so beautifully that these oddball diversions seem almost appropriate.

Really, though, this is less an actual movie and more an advanced delivery system for future Tumblr reaction images. Prince’s central performance is risky, selfless and just a hair less naturalistic than your average Tex Avery cartoon. He’s a relentless fount of expressive facial contortions. With the sound down, you would miss out on the music, but divorced from the questionable dialogue, you’d be left with a pretty thrilling silent film homage.

Other than a miscalculated downer ending, the biggest thing holding Under The Cherry Moon back is the lack of focus on the songs. The soundtrack, chock full of impressive tunes from Parade, is brilliant and well suited to the tale, but it takes a backseat to ridiculous repartee and off-kilter attempts at humor. It’s a beautifully lensed art comedy, but outside of one particularly raucous sequence set to “Girls & Boys,” it’s weirdly distanced from the greatest gift Prince had to offer us.

Now, if you’re reading this and thinking dialing the music element up in the other direction would yield better results, then you should really take a look at 1990’s Graffiti Bridge.

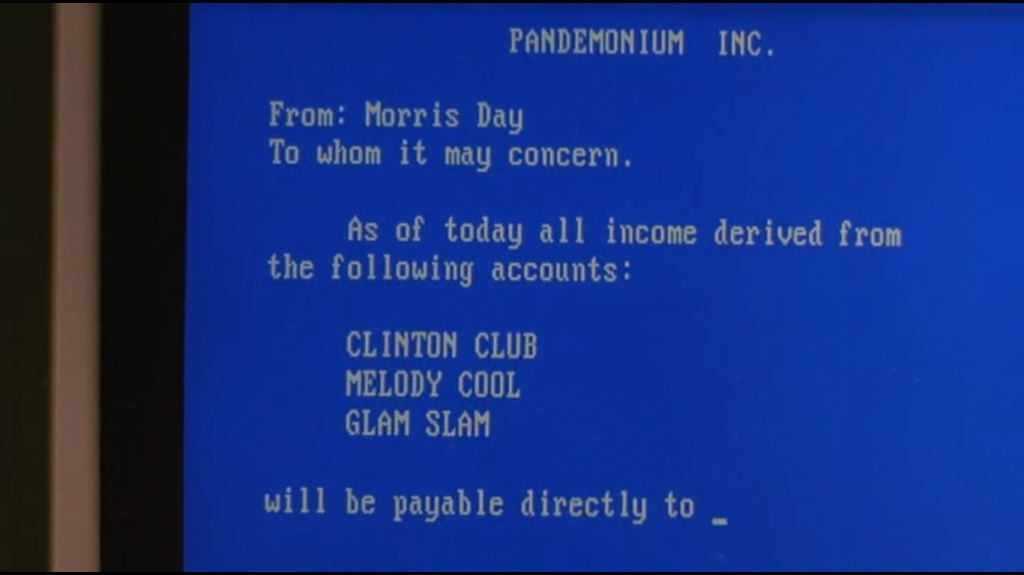

Originally conceived as a vehicle for Morris Day & The Time, this insane project devolved into a muddled, intermittently inspired sequel to Purple Rain. On paper, that’s a thrilling concept. It’s always fascinating to check back in on a set of characters years removed from the last chapter of their story to see where they ended up, but in the case of Graffiti Bridge, some endings are best left unsullied. It’s officially the early Nineties and The Kid (Prince) is now the co-owner of a club called The Glam Slam, a venture Billy from the last film left him alongside still-rival Morris Day. In the ensuing years, Morris has grown from being a funk practitioner and recreational womanizer to full on supervillain.

Morris runs a collective of criminal night clubs and has been trying to squeeze The Kid out of his co-ownership so that he can…well, look, there’s not a lot of sound motivation at play here.The two men still appear to be at war over their differing musical styles, completely sidestepping the religious revelation between them at the end of the last film. As in Purple Rain, there’s a beautiful woman caught between them as well, named Aura (Ingrid Chavez), who may or may not be an actual angel? Chavez is even more radiant on screen than Appolonia was, It’s more than a little disappointing to see all of the elements from the original film thrown back together without much thought, displaced to this new, inauthentic setting.

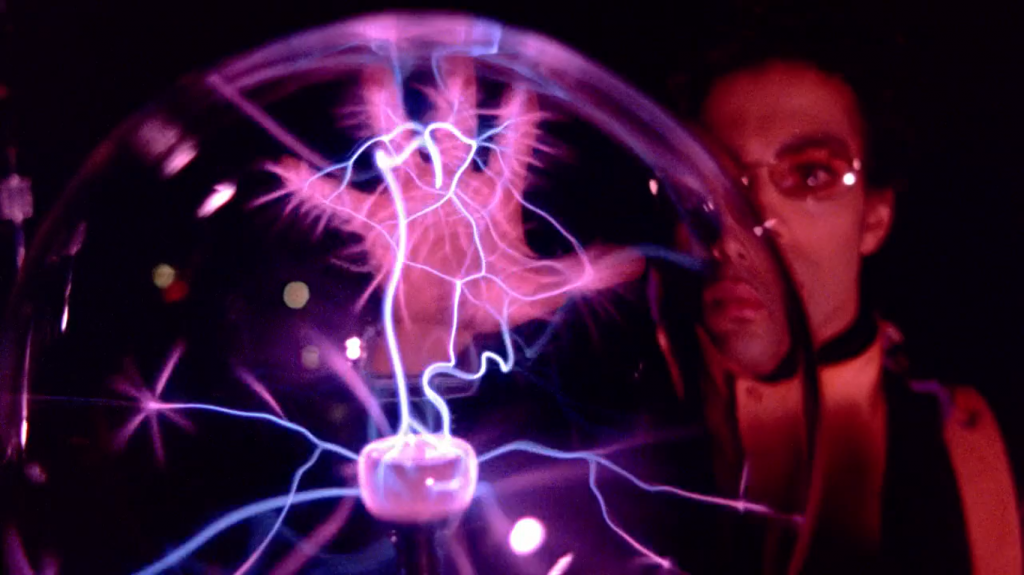

Whereas Rain took place in the very real, thriving music scene of Minneapolis, here the drama transpires in an artificial landscape so far removed from reality as to be laughable. It’s the perfect storm of ill advised aesthetics converging into one, messy melange of Nineties ephemera. Everything is shot on a back lot that looks less like a real city than Gotham did the year before in 1989’s Batman and the sharp, clean compositions of Rain have been replaced by a hyper cutty montage style cribbing Spike Lee with only half the finesse. There’s both an odor of Dick Tracy and the distinct sense that Eric Draven might stalk across the scene at any minute. It’s the outsize color and spectacle of the New Power Generation era at the dawn of its inception, still too cluttered to be taken too seriously.

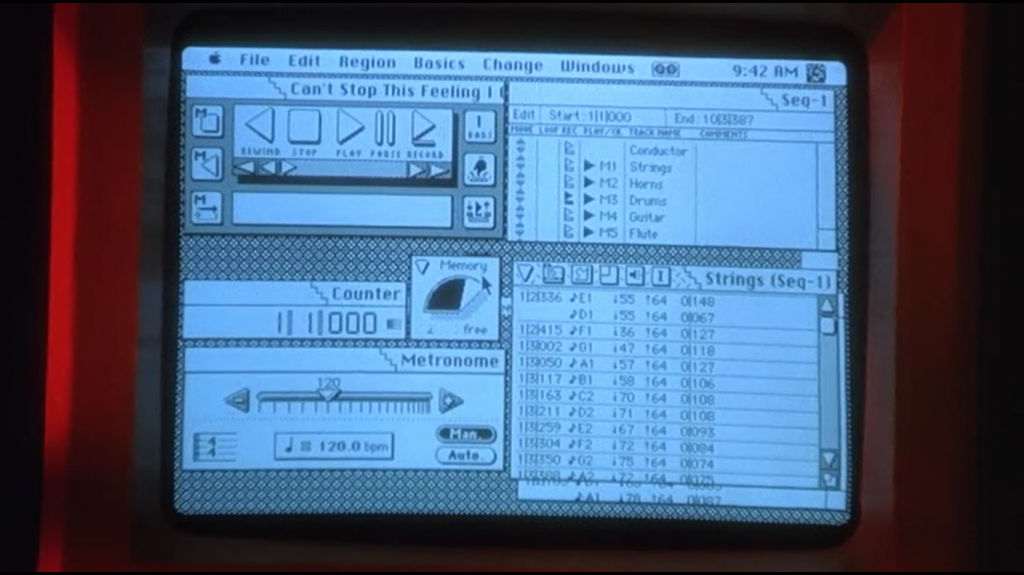

Also, this is right before Prince forsook the internet, so you get a whole lot of this:

It’s fun enough, but the plot is ineffable in its absurdity. Where Rain‘s musical performances were organic elements of the narrative, songs and dance-offs are placed liberally throughout Bridge with very little care given to their thematic relevance. Events occur without much thought. It feels a bit like the original, but it’s too all over the place to really connect. The entire film feels more like an interlude on In Living Color than a sequel to one of the greatest rock movies ever made. That semi-soulless, corporate studio sheen is largely to blame, making Bridge feel like the Mallrats to Rain‘s Clerks, to borrow a comparison to one of Prince’s future collaborators.

Prince, on screen and behind the camera, seems conflicted. His faith begins to permeate the text in a way that’s more diversionary than touching. In Rain, it was clear he was the main authorial voice behind the film’s music, even though each band had its own sonic identity. Here, this man behind the curtain puppetry remains, but it actually feels metatextually relevant. Unlike in Rain, The Kid doesn’t seem to really be feuding with Morris, but with himself, with Morris just the zoot suited manifestation of the sinful urges tainting his artistic purity. This religious fervor becomes comically apparent in the film’s last act, a gospel hewed rapture that only rings hollow for all its inelegance.

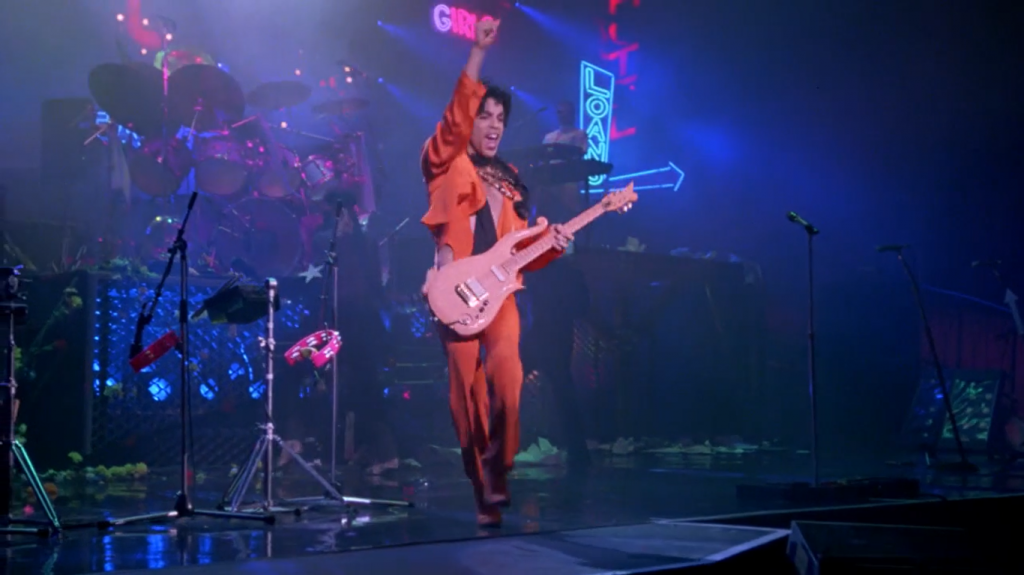

If Moon is too light on music and Bridge too heavy, the concert film released between the two films might be just right. Co-directed with Rain helmer Albert Magnoli, Sign O’ The Times is the third porridge bowl of Prince movies. It isn’t quite as blissful a depiction of Prince’s stage presence as Rain, but it maintains a smarter balance between music and film craft.

Though primarily a filmed record of a performance, Sign O’ The Times intersperses these abstract theatrical interludes throughout, drizzling morsels of drama throughout the celebration of Prince’s live show. These little backlit dioramas of relationship patter play out like music video adaptations of David Mamet’s Edmund, but they offer a context for the dense emotional aura of Prince’s music. Coupled with the clean, sweeping camera movements, the stylized set pieces and the bravura power of Sheila E’s thunderous drumming, the film traps peak Prince in cinematic amber. No longer the hungry tyro from Rain or the vaudevillian cad of Moon and not yet the embattled soul shaman of Bridge, this is a purely charismatic and genuine Prince.

It’s fascinating to study Prince as a mannequin for the various costumes he’s deployed throughout his career, especially as an actor, but there’s just no substitute for the raw, uncut powerhouse who so effortlessly burns up the screen in Sign O’ The Times. It’s a shame we didn’t get two more decades of celluloid excursions from The Purple One, but this unique period of his career lives on in these hallowed images.

If you have any films you would like to see covered in this column, hit us up on Twitter @DeadshirtDotNet and we’ll get them in front of Dom.