The world is too messed up to obsess over bad movies as much as we do; isn’t it time we obsess over good ones? In his monthly column You Have To See This, Chuck Winters reaches into his pile of flawed, forgotten, or just plain fascinating gems to figure out what makes them tick and what makes them matter.

Let’s play a game. First, I’m going to tell you the basic, back-of-the-DVD-case story of Last Train From Gun Hill, a 1959 western starring Kirk Douglas and Anthony Quinn. Then, I’m going to ask you a question about it.

The marshal of a small town, Matt Morgan, discovers the body of his Native American wife, beaten and raped. At the scene is a horse belonging to Craig Belden, a wealthy cattle baron running the nearby town of Gun Hill, who happens to be an old friend of Morgan’s. Once Morgan figures out that Belden’s son Rick was responsible for the murder, Morgan becomes hell-bent on bringing Rick to justice, causing Belden to bring all of his considerable power down on Morgan’s head. Holed up in a hotel with his quarry, Belden’s men surrounding him, Morgan must somehow get himself and Rick on the last train out of town. A classic story of Righteous Law going up against Corrupt Money, right?

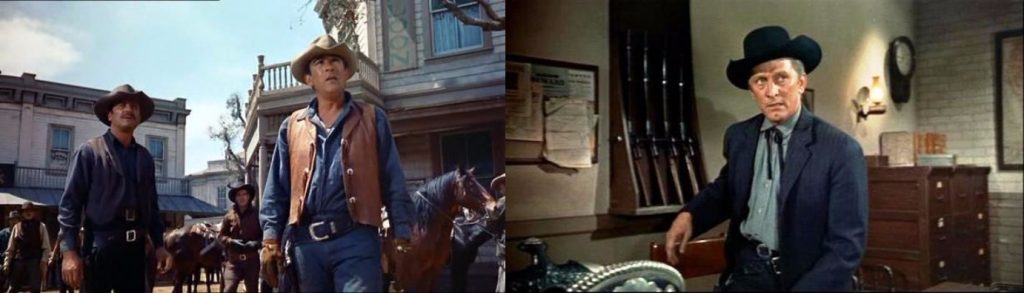

Now, look at the picture below and tell me: Who’s Matt Morgan, and who’s Craig Belden?

Last Train From Gun Hill was produced by the legendary Hal Wallis (Casablanca) and directed by celebrated workman John Sturges. Two years prior, Wallis and Sturges mythologized Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday with Gunfight at the O.K. Corral; Sturges would go on to direct The Magnificent Seven the very next year and then The Great Escape in 1963. The film was adapted from the story “Showdown” by Les Crutchfield, a regular writer for Gunsmoke. The screenplay, however, was written by James Poe, and if that name somehow sounds familiar to you, then chances are, you’re already fascinated. Poe previously worked on the film adaptation for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and would go on to adapt The Bedford Incident (a Richard Widmark/Sidney Poitier Cold War thriller that was a sort of precursor to Crimson Tide) and the Sydney Pollack drama They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Poe was the last guy you’d think of to script a typical Western; here, he turns in a simple, tense screenplay that plays with traditional Western archetypes to illustrate how easily a righteous desire for justice can turn into something ugly.

It’s worth noting that Gun Hill doesn’t make a very good first impression, though. The film opens on a Native American woman—Morgan’s wife, Catherine (an early role for ’60s TV mainstay Ziva Rodann)—out on the road with her son, where they run afoul of two drunk cowboys, the aforementioned Rick Belden (Earl Holliman) and his friend Lee (Brian G. Hutton, who would eventually direct Clint Eastwood in Where Eagles Dare and Kelly’s Heroes). The cowboys chase them down until their coach inevitably crashes, the mother orders her son to run home…and the editing gets a little wonky here, as it cuts to Rodann getting her shirt torn off by Holliman, and then over to Rodann’s son calmly mounting his horse and riding away as his mother cries out from being forced upon.

The film is quick to overcome that blunder. The more pressing issues are the ways Gun Hill feels like the dozens of other Westerns that were produced in the era. Take a look at this trailer, if you don’t mind spoilers.

They’re selling the film on the reputation of O.K. Corral. They’re painting Douglas (who played Doc Holliday in O.K. Corral) as the unquestionable hero and Quinn (the acclaimed Mexican-born actor who got his start in Hollywood playing villains and other “ethnics”) as the unquestionable villain. They’re promising a fairly straightforward narrative of justice prevailing against seemingly insurmountable odds, and those promises aren’t false. Dimitri Tiomkin (who also did O.K. Corral and High Noon) even turns in a score that sounds of a piece with other Western scores of that era.

That straightforward narrative is a gloss, though. If you’re paying attention, it’s clear even in that trailer that something’s a little off here. Look at the costuming on Douglas and Quinn. For a villainous cattle rancher who owns an entire town, Quinn sure is dressed casually; he even wears a white hat. Meanwhile, what’s our hero Douglas wearing? Black jacket, bolo tie, black hat. You are, of course, free to assume that it’s a freak ironic coincidence. You’d be assuming it of costume designer Edith Head, the 8-time Academy Award winner who served as Brad Bird’s primary inspiration for The Incredibles‘ Edna Mode, but it’s still your right.

Moreover, if you know your classic movies, you’ll know that Anthony Quinn won one of his Oscars for playing Paul Gauguin, close friend of Vincent Van Gogh, in the 1956 film Lust For Life. Who played Van Gogh? Kirk Douglas. Meanwhile, Earl Holliman (who also played Anthony Quinn’s son in Hot Spell, which was also produced by Hal Wallis and also scripted by James Poe) previously played wide-eyed Wyatt Earp deputy Charlie Bassett in O.K. Corral.

It’s stunt casting, but it’s stunt casting that works when you see the film: the previous history between Douglas and Quinn helps create a shorthand for old friends Morgan and Belden when the film doesn’t have any room to establish it. Moreover, Holliman’s babyfaced charm gives Rick Belden an interesting edge. Rick is clearly a spoiled brat, but he’s not built to be a killer; he’s a boy who’s been given certain ideas about what it means to be a man from his father, ideals that he repeatedly fails to live up to. His choice to take Catherine is entirely about subconsciously proving something to his father, right up to the moment where it all went wrong; afterwards, it’s a stain on his soul, and for all the shit he talks, it’s clear he feels a guilt that will never leave him, even if he somehow escapes Morgan’s justice.

As for Rick’s father, it’s easy to see that respect is important to Craig Belden. There’s a great scene early in the movie where he and Rick are having a talk, and one of Craig’s men steps in with a disrespectful joke about Rick’s lack of experience with women. Craig immediately orders Rick to fight him, and also tells the man not to hold back. Rick gets his ass kicked, but after Craig picks him up and dusts him off, he expresses how important it is for a man to stand up for himself, win or lose. You can see how this kind of parenting has completely damaged Rick, but you can also see the honorable intent in it. It’s obvious that Craig Belden grew up under humble circumstances, circumstances he still feels connected to. It shows in Quinn’s passionate performance. It shows in the respectful way he treats the men under him and vice versa. And, of course, it shows in the brilliant, casual way that Head dressed him.

Belden’s look is a stark contrast to Matt Morgan’s darker, more formal style. He arrives in Gun Hill claiming to represent the law, but he wears his badge on his shirt, under his black jacket. Your first impression of Matt Morgan in that outfit is not a man of the law, but a man in mourning. Even when Morgan takes the jacket off to reveal the Marshal star underneath, when he insists that his crusade to get Rick on the last train out of town is about justice, Sturges’s camera insists otherwise, drenching Morgan in hard shadows that obscure his badge. A little later in the movie, Morgan further betrays the anger that drives his sense of “justice” by coldly telling Rick about the road from trial to hanging. It’s a twisted piece of writing from James Poe, a villain’s monologue coming out of the hero’s mouth that Douglas tears into like the Tasmanian Devil, blurring his character’s moral standing considerably.

And yet, the film undercuts that moral ambiguity, because the ’70s haven’t happened yet and the film needs a clear hero and a clear villain. So, Belden’s character gets dragged through the mud a bit. The townspeople seem to fear him more than they respect him, even though he doesn’t really act in a way that would inspire fear. And on top of that, while we don’t see him actually beat women, his love interest Linda (Carolyn Jones) is perfectly happy to remind him that she spent ten days in the hospital because of him. While they’re alone together. In a tone that suggests more offense than fear. I mean, Linda’s supposed to be a tough, no-bullshit kind of character, but…really?

Studios are studios; suits are always going to have their say, and there’s a decent chance that what they say could be actively harmful to what the film they’re responsible for is trying to do. But I’m open to the idea that this is an entirely unforced error (even before factoring in the attitudes toward domestic violence in the ’50s). To be sure, John Ford had dropped The Searchers on an unsuspecting world in 1956, which deconstructed the mythical figure of John Wayne that Ford had helped build. That movie likely opened the door to the more complex characterizations that define the two main hands of Gun Hill. But it wouldn’t be until ’62 when Ford and Sam Peckinpah started to really dissemble Hollywood’s romanticized vision of The Old West with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Ride the High Country. Wouldn’t be until ’69 when Peckinpah blew it up altogether with The Wild Bunch. Given all that, Last Train From Gun Hill is a curious half-measure, a film that’s constantly on the verge of a breakthrough that it doesn’t quite know how to reach. It’s almost like watching a thirteen-year-old boy trying to explain Zen philosophy to his friends.

And yet, it does interesting, dramatically stirring things trying to get there, things you probably didn’t think were possible back in this era. Kirk Douglas’s constant straddling of the line between lawman and avenger is somehow more fascinating than if he had played Matt Morgan as a straight antihero, and Quinn’s soulful performance as a man of power, whose typical pride manifests itself in a unique, far more personal way, brings to life one of the most compelling antagonists I’ve ever seen. You’ll never not root for Matt Morgan to succeed. Still, your heart will always break a little for Craig Belden, whatever indirect responsibility he bears for this mess. There’s a psychological complexity at work here that eludes even many modern movies, Hollywood and independent.

Even with all its concessions and its missed opportunities, that complexity matters. It matters because a genre that so thoroughly informs our American identity needs the occasional movie that raises tough questions about its hero and shows some sympathy for its villain. It matters because movies mature in stages; they don’t go from Gunfight at the O.K. Corral to The Wild Bunch without a few stops along the way, which makes a middle ground like this, however flawed, historically significant. Most of all, though, it matters because it’s just fucking cool.

If you know of any movies that you think deserve to be covered in “You Have To See This,” feel free to tweet your suggestions to @DivisionPost!