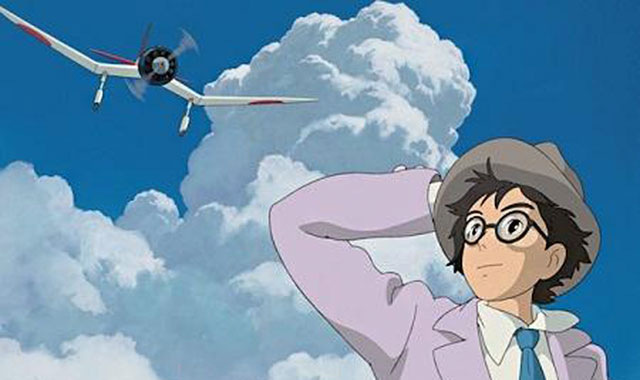

If The Wind Rises is to be the truly last of Hayao Miyazaki’s legacy, it is somewhat of a different ending that his fans might have hoped for. Director, animator, illustrator, producer, and screenwriter, a long career of moving and beautifully rendered films comes to a bittersweet conclusion in the fictionalized biography of Japanese aircraft designer Jiro Horikoshi.

After its July 2013 international release for the film festivals, the film has finally made its way to wide release in US theaters.

Synopsis (Spoilers Ahead)

Young Jiro Horikoshi dreams of building fantastic planes. His dreams are haunted by dark inklings of warfare, but also visited by his idol, real life Italian aeronautic engineer Gianni Caproni who inspires him to take a career designing planes.

Jiro meets a young woman on a train ride, quoting French poet Paul Valery,

“The wind is rising! We must try to live!”

Their fates are abruptly thrown together as they find themselves amidst the tragedy of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The young lady’s maid breaks her leg and Jiro, who is naturally giving and helpful, escorts the young lady home and gets help for the maid. He disappears to put out fires at his university before the family really gets a chance to thank him.

Jiro’s designs are innovative and he finds work as an aeronautical engineer at a top company with military contracts. Still, Japan is decades behind the Western world with their technology and Jiro’s design stretches their capabilities too far, ending in a crash during the test flight and the contract being given to a competing company. Jiro’s brilliance and hard work does not go unnoticed by his supervisors. Jiro and his fellow engineers travel in the bitter winter to study the metal engineering of German aeronautic technology.

In Jiro’s dreams, Caproni gives voice to what idealist Jiro struggles with, how his desire to create beautiful and innovative things will come at the human cost of what they will be used for. Caproni asks him,

“Would you rather live in a world with pyramids, or without?”

Jiro’s ambitious designs again end in failure. On sabbatical at a mountain resort, Jiro reunites with the young lady from the earthquake, now a grown woman called Naoko, and they fall deeply in love. His feelings for Naoko spawn the idea for the design of his masterpiece plane. A dark shade is cast over this lighthearted time with whispers of the German SS and Hitler’s Germany.

Naoko reveals that she is suffering from tuberculosis and vows to get well at sanatorium so that she can join Jiro in Nagoya as his wife. As Naoko’s condition only worsens, Jiro buries himself in his work and pines for her in letters. Naoko realizes the gravity of her condition and decides to join Jiro in the time she has left. They marry in a tiny, touching ceremony in his boss Kurokawa’s home. After many sleepless nights, Jiro’s innovative design for the Type 96 fighter succeeds, but Naoko leaves him as she worsens in health, retreating to die at the sanatorium so as not to be burden.

Jiro meets Caproni in a final dream, where the rolling hills have become an overgrown graveyard of the skeletons of his bomber planes. The planes take flight soaring into the pastel sky and Naoko flies as well. It is only in Jiro’s dreams that the world can remain beautiful.

What Works

Hayao Miyazaki’s best works whisper of Shinto-ism, and even a film about engineering is imbued with his appreciation for nature. The artwork, especially in Jiro’s dreams, is a watercolor fantasy that contrasts with the stark mechanical images as the Japanese army looks to the German industrial complex of the Third Reich for air force technology. Naoko paints flowers on hopelessly windy hillsides. Jiro’s early airplane designs are reminiscent of swallows; his friends tease him for taking inspiration for wing structure designs from the mackerel bones of his lunch.

The horror of the earthquake in 1923 is captured perfectly with the animation; the hills and the towns riding on them roll in obscene waves and rupture, bursting into flame. Instead of sound effects, a low eerie notes of a men’s choir moan as the refugees head away from the burning city.

Under Miyazaki’s direction, the most meaningful parts of the story are found in small details. One of the most heart-wrenching scenes is when Jiro falls asleep with only his head on the pallet that Naoko had been sleeping on. She covers him and scoots to the end of the matt to be on the edge with him. To me, this simple gesture says love more powerfully than a thousand Disney ballads. Miyazaki’s mastery comes in his ability to use nuanced details to show and not tell the audience how they are supposed to feel.

In the US release, voiceover work is a full line-up of well-known American actors. Joseph Gordon Levitt lends his vocal talents Jiro and his friend and rival engineer Honjo is played by a more cynical John Krasinski. A nearly unrecognizable Emily Blunt voices Jiro’s wife Naoko Satomi.

Overall, the film is a masterwork, a nostalgic pre-war rendering of Japan that Western audiences did not know they could miss. The story it tells is heartbreaking, but layered with pride and hope.

A Few Faults

Miyazaki’s works have always taken an anti-war and anti-industrial stance, but often in a fantastical context, in worlds at least a little removed from our own, such as Nausicaa: Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke. The Wind Rises takes place in modern history, but handles the issue with a light touch. It’s less of a stance and more of a sentiment. Likewise, Jiro’s idealism is cushioned by the gentle handling of those around him, especially his friend Honjo and his boss Kurokawa, as if he and his dream are so frail that the world around them would crush him. Even sickly Naoko attempts to shelter him from the burden of her illness.

This film could easily have been told as in live action and not an animated picture, but the plump animation style of Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli seems to serve as format only to soften the blow.

While family-friendly, The Wind Rises is not a children’s film because of the complex moral dilemmas faced by its characters, as well as the length of the film. This movie is sad and beautiful and I made the mistake of taking my boyfriend’s six year old nephew to see it. Please do not being children to this movie unless you want explain why people used to smoke so many cigarettes, tuberculosis, and the uneasy loyalty between Axis powers in WWII.

Miyazaki’s remaining body of work would be a much better starting place to experience the whimsy and danger of his worlds, especially through the eyes of a child.

Conclusion

The Wind Rises is certainly a bittersweet experience. The fantastic reaches of Miyazaki’s imagination and Studio Ghibli’s characteristic animation soar, but the nature of war grounds the film in a moral struggle of art versus military utility. If there is a message to take from this film, it is that life is only a beautiful dream, so we must make it as beautiful as possible because it is so fleeting. It is worth multiple watches, but impossible not to be teary-eyed.

The Wind Rises is out in limited release in theaters nationwide.