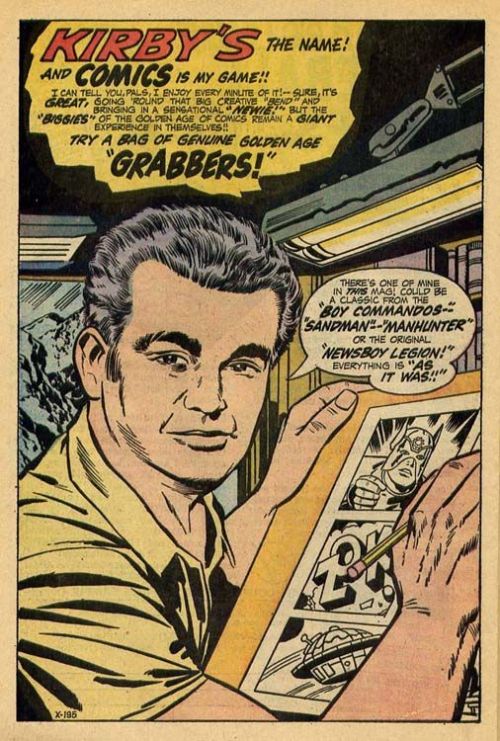

Jack Kirby would have been ninety-seven today. I’m positive you won’t be able to swing an uplifted mutant man-cat in any comic-friendly corner of the internet without hitting a dozen articles detailing the history of Cap or the Fantastic Four or any of a newsboy legion’s worth of Kirby creations that went on to achieve worldwide recognition and acclaim. If you’re looking for an affecting story or a striking character that cast a shadow over countless comics printed in its wake, you’ve got an embarrassment of riches when it comes to Kirby’s oeuvre. The man was producing material through the entirety of the Gold, Silver, and Bronze ages of comics, he’s the diamond standard of what it means to generate a prolific body of work. Effectively? He’s everywhere. Jack Kirby changed the way that comics told stories, it would take herculean effort to overstate his contributions to the genre.

With that in mind, it’s not at all surprising that so many of Kirby’s creations are still represented on the page today, and so many have traveled through the hands of talented creators over the years. This is one of the benefits of the type of long-form serialization that typifies comic storytelling, passed from one writer to another the excess details, the flash from the mold, perhaps, is stripped away. On a long enough timeline, and with a decent run of consistently adept creators, this renders the core of the characters evident. At a glance, it’s simple to see why these characters are such powerful symbols, why we keep returning to the same well and pulling out different interpretations that can still carry the same weight. In a few cases (sorry Jack, but I’m looking at the X-Men) later writers have succeeded so thoroughly in refining the core themes of characters that they render the original appearances almost unrecognizable. But that’s not always the case.

Today I think we should take a moment to examine some characters that, even though they’ve outlived their creator, are still quintessentially Kirby. Let’s talk about 1971 and the birth of The New Gods.

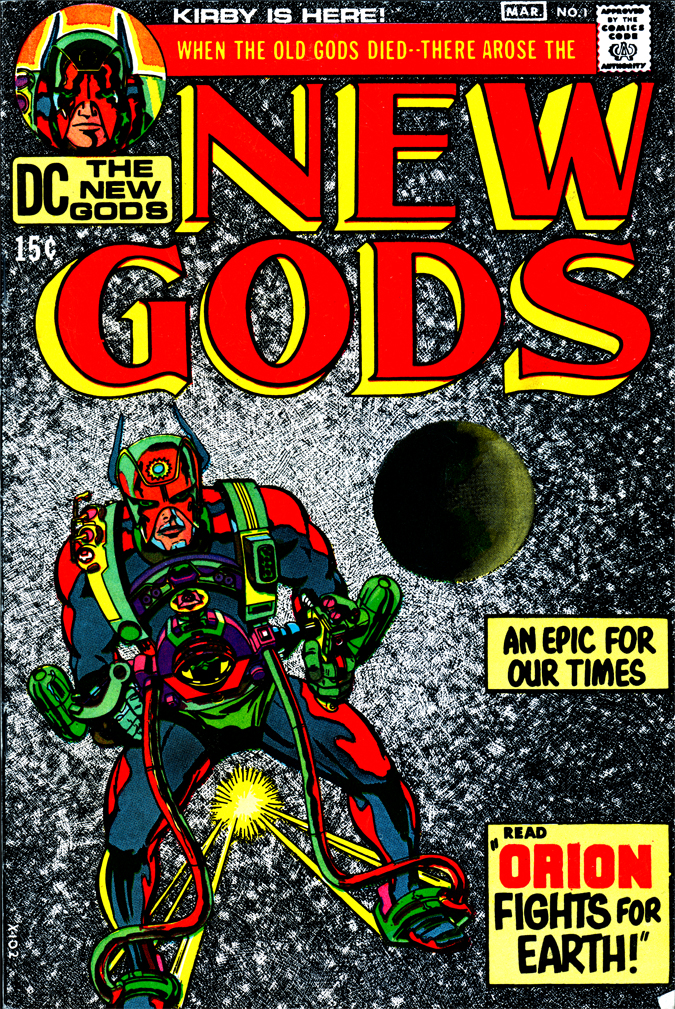

This is going to be a bit of a bold statement, but everything you need to know about the way that Jack Kirby tells stories you can distill from The New Gods. That said, though the initial eleven-issue run is excellent, the entirety of the Fourth World Saga might not be the most new-reader friendly. Taking place over the course of a number of ongoing series, the story can get a bit byzantine, and while as a whole the Fourth World and its successors constitute arguably the platonic ideal of what makes Kirby work, it can be more than a little daunting to someone laying eyes on it for the first time. While I don’t think anyone with an interest in comics should go without reading the Fourth World Saga, if you’re in a hurry that initial run of the New Gods still crystallizes what you should take away from a Jack Kirby story.

High Stakes. Big Emotion. Big Action.

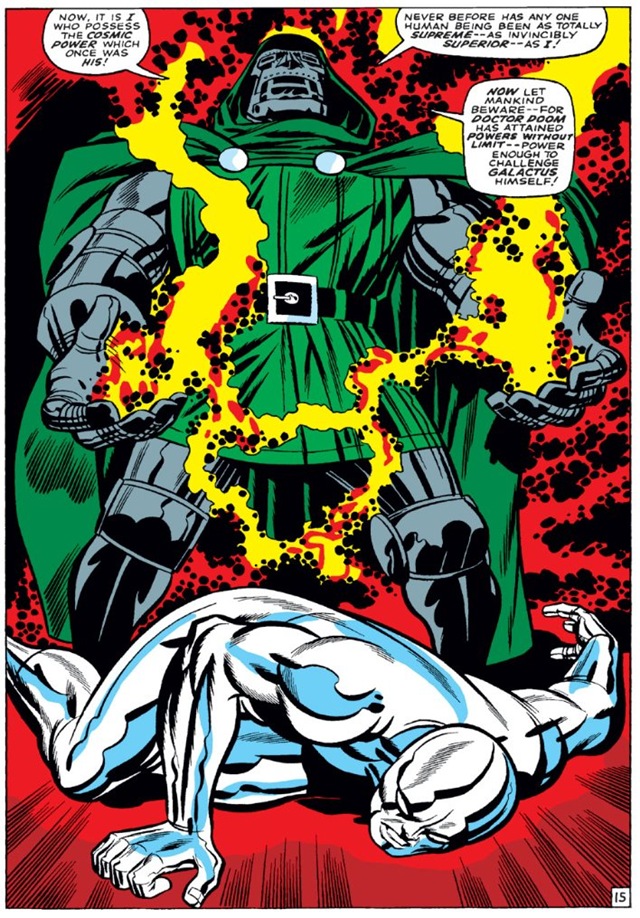

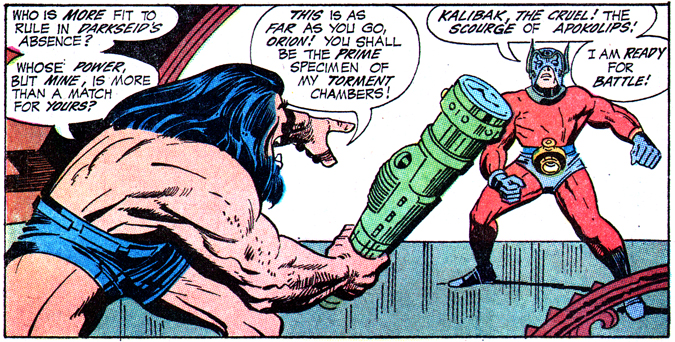

“Small” is not a word that you throw around very often when discussing Jack Kirby. He was a writer interested in vast, bleeding horizons of story, operatic, boiling-point emotional conflict, and bombastic, tactile action. Kirby’s art is heavily stylized and everything on the page is heightened. Bodies in Kirby’s work are muscled to the point of appearing as sculpture and every pose they strike, whether in the midst of combat or languishing in pain, is exaggerated in sweeping, almost titanic gestures. If these images intended to tell a more reserved story they would come across as comical, histrionic, but they fit in the service of the epic Kirby is attempting to weave. The art in these initial eleven issues is characterized by its confidence. From frame to frame the command of movement in the battle scenes allows the fights to play out as dynamic, and yet the bold statuesque figures Kirby uses mean that they never lose a sense of gravity.

What’s especially important about the excellent the action in these issues is that it’s all in service of the emotions at play. If there’s one way to describe the way that Kirby approaches his characters, it’s sincere. Much a fan as I am of the wry, world-weary, Whedonesque, wink-and-a-quip approach to self-aware storytelling, it’s the polar opposite of the way that Kirby does business. His characters have massive, soap-operatic problems that they deal with by delivering unto one another huge, crunchy, punches in the face. That’s Kirby Storytelling 101; to call it “broad strokes” is missing the big picture. Certainly we’re dealing with the issues at play in broader terms, but what works so damned well is the confluence of all of these blown-up, unapologetic approaches to story conspiring with the dire feeling of size and calamity that the stakes imply to make the reader believe that they’re reading a battle for the fate of humanity. In a lesser writer’s hands, that would just be a tagline.

Myths and Their Responsibility as Stories

There are some context clues to let you in on the fact that Jack Kirby is attempting to create his own mythic legacy through this story. Part of it could be the fact that the very first issue shouts “AN EPIC FOR OUR TIMES!” on the cover, part of it might be that the story is called The New Gods and goes out of its way several times in the first issue to explain that they’ve arrived to replace the Old Gods of mythology. That’s on the cover as well. That’s not exactly a modest goal and Kirby wrestles quite a bit with the common language of mythology in this first series.

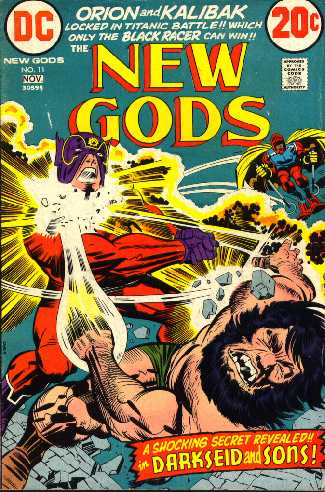

We enter into the story of the New Gods en media res, which is about par for the course in most myths. That’s one of the many things that mythic stories have in common with modern comics, and yes, it may be too neat by half to simply assign the roles of various gods and goddesses to modern comic heroes and call them our new cultural pantheon, but it would be dismissive not to acknowledge the similarities between comic superheroes and mythic champions. For one, there’s the common trope of a hazy sense of chronology and a respect for the status quo. As far as western mythology is concerned, a controlling percentage of stories seem to take place at an essential myth-time, where chronology and the sequence of events of broader stories are not as important as the story at hand. To a dedicated comic reader this might sound a bit sacrilegious, but it’s important to remember that any comic a new reader picks up may be their first and the characters at play need to remain recognizable to someone with at least a vague idea of the universe in order to pique their interest. To this end, Kirby begins his epic with the destruction of the old world and the beginning of the new. Yet, after the groundwork is laid, he skips ahead decades to a world with established relationships, alliances, betrayals, and conflicts. By the time Orion and Metron convene with the Highfather in the very first issue we already know the foundation upon which this universe is built. This is Kirby telling us through the structure of the story itself that the battlefield we are about to enter is a mythic one.

At its conception, The New Gods was not intended to be an ongoing piece. Initially the core conflict was to be resolved in a battle between Orion and Darkseid that would leave both of them dead. If this had been allowed to occur, it’s up to question whether or not they would have lived on in forms so representative of Kirby’s particular style as we have now. I’ve no doubt they would have been brought back (it’s hard to keep a good Kirby idea down) but perhaps it was the sheer mythic quality of their first appearances that lead to their depictions remaining so recognizable as Kirby creations over the years.

Philosophy, the Sanctity of Life and the Concept of Anti-Life

The best barometer for nailing down Jack Kirby’s philosophy is the fact that he created the Anti-Life Equation and made it a serious, dangerous concept in the larger DC Universe. To someone unfamiliar with the cosmic level of the DCU or Final Crisis, or any number of other stories that used the Equation as a MacGuffin, this might seem like another vestige of Silver Age frippery. After all, why not just call it the Death Equation? The answer is that, to Kirby, Life and Anti-Life in the New Gods and in the greater Fourth World Saga are much more complicated concepts. Life to Kirby represents much more than just a biological contingency to allowed continual corporeal existence. Life in the New Gods means a freedom of choice. It means youth and celebration and yet carries the ability to make mistakes. When the “Life Equation” is first introduced, it’s in a scene that projects a rather dire prophecy to Orion, the Highfather, and Metron, and yet it hammers home the fact that, even though this prophecy is advising a certain course of action, it is up to Orion to follow its instruction. In The New Gods the concept of Fate itself defers to Free Will.

That brings us to the opposite, the Apokolips to the Life Equation’s New Genesis, the Anti-Life Equation. As soon as the concept of Anti-Life is acknowledged, Kirby is quick to inform us that Anti-Life is not necessarily death, rather Anti-Life is subjugation, the absence of freedom. That’s not to say that murder is all well and good–after all the fact that the denizens of Apokolips long for death as a goal says a great deal about their own philosophy–but the fact remains that death is a part of life, as a concept it is not necessarily an antagonistic force. Well, for Kirby and the New Gods, death as a concept is a cosmic black knight on space skis, but that’s really besides the point. The New Gods illuminates Kirby’s philosophy in that it acknowledges that the opposite of life and freedom and creativity and prosperity is not death, but rather the loss of agency.

In The New Gods, and to a larger extent in the Fourth World Saga, what Kirby’s stories tell us is that dying is inevitable, but it doesn’t invalidate the choices that someone makes, it doesn’t make the things they say or write or draw any less true. Only silencing them before they’re heard can do that.

Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby

August 28, 1917 – February 6, 1994