Every Thursday, our staff of pop culture addicts tackles a topic or question about movies, music, comics, video games, or whatever else is itching at our brains.

As a culture, we invest a lot into the lives of fictional characters, so much so that sometimes it feels as if the characters are investing back. Just like real-life friends and mentors, fictional characters can influence, help shape our interests, our personalities, the paths of our lives. While the real people change, evolve, and often, let you down, imagined idols can be whatever you need them to be, a static example of what kind of person you want to be.

This week we decided to reflect on some of the imaginary role models who gave us something to believe in.

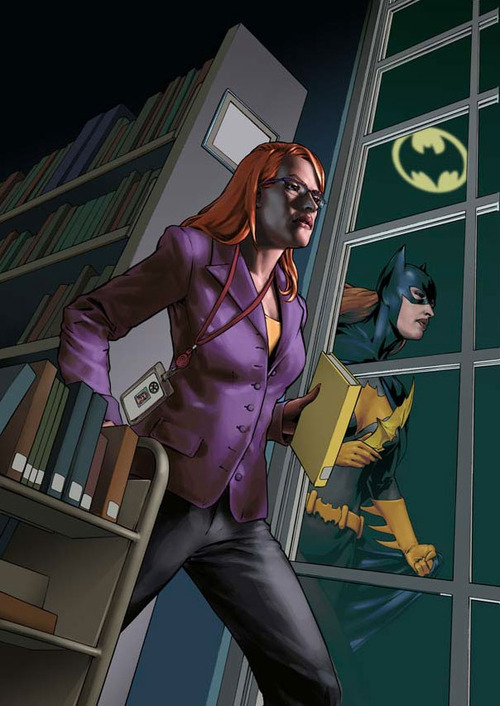

Barbara Gordon from DC Comics (1967-)

Art by Gene Ha

My first exposure to Batgirl and Barbara Gordon (“Babs” to her friends) was Batman: The Animated Series and its later evolution as The New Batman Adventures. Batman had been my favorite hero ever since I saw the 1989 film until, that is, I discovered the cartoons and felt an instant connection with his younger counterpart in my after-school marathons. Batgirl was portrayed to be as intelligent as Batman but, at the same time, she was witty and far less grim; plus in the later series, she rocked some killer yellow boots and black lipstick. Similar to Dick Grayson, she could find some fun in the fight even when the stakes were high. In my childhood, I wanted to be Batgirl, but it wasn’t until later when I discovered Oracle that I began to look at Barbara Gordon as a person.

At the beginning of college, a friend (who later became my husband—coincidence?) convinced me to read Batman: No Man’s Land, which was my first graphic novel experience. I devoured the entire collection in two days. The series was integral in shaping my passion for comics, and it was also my introduction to Barbara Gordon as Oracle. After the events of The Killing Joke, Barbara became a completely different kind of superhero, and I was elated that comics could portray such an incredibly strong and enduring female character in this way. She was able to flip her tragedy on its head, becoming an even more essential part of the Bat family by artfully fighting crime from a wheelchair. Of course, the trauma of losing her legs was still an ongoing battle, and while it affected her deeply, she never let it win.

It wasn’t until I backtracked to Batgirl: Year One that I got to know Barbara Gordon the librarian. Not completely satisfied with her current job, Barbara tried to pursue a career as a cop but was foiled by her well-meaning father and the precinct’s issues with her gender and size. Instead of giving up her dream, she forged her own path into vigilantism, and the rest, as they say, is history. This series reminded me of a poster that hung in my college library featuring Barbara as a librarian. The image of her delivering what I imagine is the perfect book to a needy patron is mirrored in her reflection as Batgirl. The caption at the bottom read, “Librarians are heroes every day”. It was the first time I really understood that her day job was just as heroic as her after hours antics; both versions of her were dedicated to helping people and doing good. It was this image that came to me as I was looking for jobs after graduation and happened upon an open position at my local library. It was a hard truth to face when I realized a comic book character was the thing that tipped the scales toward my career choice, but five years later I’ve assisted hundreds of people as a librarian. Working with the public is not easy, but on my worst days, I like to think of Babs and how’s she been with me all these years teaching me to do the right thing.

– Sarah Register

Calvin from Calvin and Hobbes (1985-1995)

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then my eight-year-old self was paying serious compliments to cartoonist Bill Watterson and his famous creation Calvin. I’ve read and enjoyed Calvin and Hobbes comics almost as long as I’ve been alive, but at first I didn’t find it as funny as less sophisticated comic strip mainstays. But around ‘94 or ‘95, something clicked in my head and I started to understand just a fraction of the storytelling, irony, and imagination that set Watterson’s six-year-old avatar apart from the rest.

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then my eight-year-old self was paying serious compliments to cartoonist Bill Watterson and his famous creation Calvin. I’ve read and enjoyed Calvin and Hobbes comics almost as long as I’ve been alive, but at first I didn’t find it as funny as less sophisticated comic strip mainstays. But around ‘94 or ‘95, something clicked in my head and I started to understand just a fraction of the storytelling, irony, and imagination that set Watterson’s six-year-old avatar apart from the rest.

Both Calvin and I were incredibly verbose children who were frustrated with the world. But where I was a literal-minded goody-two-shoes, Calvin was an elemental, selfish, joyous force. I started “playing” Calvin and Hobbes the same way as I would “play” Batman or Star Wars, but it soon went further than that. I began openly shaping myself to be exactly like Calvin. I purchased a stuffed tiger, named him “Hobbes,” and began treating it as a friend. I enlisted bemused friends into my very own chapter of Calvin’s Get Rid Of Slimy GirlS club, though I made sure they understood that Hobbes was the perpetual President (second to my own “Dictator-for-Life”). Not only did I create my own three-in-one cardboard box (transmogrifier, duplicator, time machine), but I would act out plotlines exactly as they appeared in the comic, including portraying my own “evil duplicate” at school for an entire week.

This story doesn’t have quite the crash-and-burn you’re expecting. While my peers found my fixation on my stuffed friend inexplicable, they had pretty much always found me inexplicable. But because I’d seen Calvin do it all before, I had such an unshakable confidence in my new activities that I actually gained friends. Moreover, as my doggedly literal imagination fixated on making myself more like Calvin, it paradoxically became a more metaphorical, open imagination, just as Calvin has. And I was still too restrained to get into any real trouble, even as my “evil self.” I never had an epiphany that it was time to stop mimicking Calvin. As time passed, I let my imaginary games diverge more and more from Calvin’s precedents. But I never stopped reading the comics, and I never forgot the inspiration I gained from them.

– Patrick Stinson

Hallie Parker from The Parent Trap (1998)

When I was a kid, as far as I was concerned, I was a dude. It’s not that I had any sort of gender dysphoria—I wasn’t unhappy with my status as a girl, nor did I want to actively be a boy. It’s just that when I thought about the ultimate trajectory of my life (which I did quite often for an eight-year-old), I thought with the voice of a male narrator. And why wouldn’t I? As far as I could tell, everyone important was a boy, and since I was sure as shit important, I must be one, too. I manifested this belief as many girls do, by tomboying up in dirty jeans and skinned elbows, and adopting a general disdain for my sister’s pierced ears and my mom’s nail polish. The girls I did relate to had a similar fuck-all approach to their gender: Little Women’s Jo March, Pippi Longstocking, and overalls-clad Mary-Kate Olsen made the cut by being practically sexless.

Enter Lindsay Lohan, 1998, as Hallie Parker in The Parent Trap, to shatter all my preconceived notions of very-small-womanhood. Smart, independent, athletic, and dry, she easily fit my criteria for a person’s worth. But Hallie was more than that: she was girly. She had pierced ears. She had side bangs. She wore blue nail polish. She was heartbreakingly pretty without being delicate. And her undeniable girl-ness just made her that much more fucking amazing to me. She could beat you up and she had a crush on Leonardo DiCaprio.

“Bad to the Bone” literally played when she entered the room. Even writing this now, I am flushed with that same feeling of complete awe that can only felt in the presence of Absolute Coolness (see: her adoring posse in the above pic). I cut my own Hallie Parker side bangs. I started wearing blue nail polish as soon as I could drag my mom to the store.

Just like that, the male narrator in my head was gone. It was replaced with the husky but undeniably feminine voice of Lindsay Lohan. She was the girl I wanted to be.

I wish I could tell you that my emulation of Hallie Parker was limited to my pre-teen years, but I would be lying if I said I didn’t think back to her when I finally got my ears pierced at 14, or when I dyed my hair red at 21, or when I bought that track jacket at Target last week. Hallie might be forever eleven, but she will also forever be older than me, and cooler than me, and girlier than me, while still being a total hardass and probably the person I still most want to be on this entire planet.

– Haley Winters

Missy Pantone from Bring It On (2000)

I lived for Bring it On when I was about 12, and I wanted to be Eliza Dushku’s Missy, and pretty much every sarcastic supporting female with a fiercer sense of style.

First of all, Eliza Dushku is always a badass, and you’re lying if you’re a Joss Whedonite and you say you’ve never wanted to be her. Missy was a new kind of rebel in the high school movie genre, and her audition scene pretty much said everything it needed to about her character. First of all, she walks in as your typical “grungy rebellious youth,” but she immediately subverts the stereotype. Her tattoo is drawn on; this is an image of herself that she created and decided to project, and it’s erased when it no longer suits her ambition. As the new girl in school, she makes a point to strike out on her own, and then whips out her badass gymnastic skills out of nowhere. She tries out for the cheerleading squad because she wants her talent to be recognized, not because she cares about team sports or social status.

My high school trajectory was similar. At my high school, being involved in Theater, Chorus, and Marching Unit didn’t make you a nerd, and success could actually put you way high on the social hierarchy. I joined color guard as a freshman and found a great group of girls, but I was never the “school spirit” type. I didn’t want to be a loner, but I was fine with remaining on the fringe of the crowd as long as I was a part of something bigger. And while I don’t care as much about the group aspect or competitions, I did have ambition and care about being my best in that context.

Later on in the film, as Missy becomes friends with blond perky Torrence (Kirsten Dunst), she acts as a perfect foil. As a viewer, you might be very aware that Torrence is the focus of the film, but you respect Missy a lot more. Missy is confident in who she is and what she wants, and she’s never afraid to be brutally honest to naive and sometimes whiny Torrence. She also knows how to be a social chameleon when she needs to be.

Missy’s cool, aloof attitude and personal style, the secret passion bubbling inside behind it, and a genuine longing for companionship were things I saw reflected in myself. So, I became more caustic in my attitude, more punk in my dress, and more serious about making sure I was delivering my talent even if I didn’t care about the overall group. I didn’t want to be Torrence. I wanted to be the person who just looked really cool and untouchable, so that when they showed up onscreen or delivered their one-liner, they were the most memorable contribution to the scene. I wanted to be the snarky supporting character with an edgy style. This is how I see myself even now through the various bellydance performance groups and circles I travel in on my way to going pro. I don’t like to overly promote myself or my experience in my bios for performances, so that people are taken aback in the cases when I fucking DELIVER. What I learned from Missy was you can still express yourself and look like a rebel, but it’s not so terrible to like and be good at mainstream things. And by the way, my tattoos are real.

– Madie Coe

Isabelle from The Dreamers (2003)

I saw this movie when it first came out, at which point I was fourteen. I was a precocious teenager, both intellectually and sexually, so Bernardo Bertolucci’s then-latest venture seemed like a good fit for my figuratively wide, if overly critical, young eyes. Eva Green blew my mind in her first film role as Isabelle: she walked around on camera with an ease I’ve never perfected, her beauty was the kind that made me feel more beautiful in its simulated presence, and she was, above all things, cool.

Everyone makes a big deal about the portrayal of transgressive sexuality in The Dreamers, which centers around the interactions between a young American film student, Matthew (Michael Pitt), and the equally cinephilic twins, Theo (Louis Garrel) and Isabelle, whom he meets in Paris in May 1968. Bertolucci sets these interactions against the leftist student revolts of the same year, gradually raising the stakes of the former as the latter intensify. Isabelle practically lives in the cinema and devours art and other cultural products with a visceral joy; this makes the explicit sex of the film seem almost like an afterthought, which probably made the experience of watching it less intimidating for me.

At the time, I, like Isabelle, was also a virgin who tried to project a worldliness grounded in the French New Wave films, 1970s vinyl, and half-understood Marxist literature I used to obsess over. I lived in a state of heightened reality where I fixed my eyes firmly on things outside of my immediate experience: I liked the most concentrated expressions of emotional upheaval and the way they provided an escape from my low-income, suburban life with my increasingly estranged parents. At the time, and it makes me feel a little pathetic to put it this way, I truly thought I might grow up to become Isabelle one day.

Of course, I didn’t exactly fantasize about entering into a borderline incestuous relationship with my brother, as Isabelle does. That aside, though, I could never be Isabelle. I was a fat teenager, and I grew up to have the body of a boxer, which negates fitting into well-tailored Mod tops. I’ll never have Eva Green’s willowy body that can wear mini skirts without inadvertently flashing everyone. I spent a lot of time trying to attain the vibe that I thought would meet my own expectations of what the adulthood I so desperately sought to enter might be. Adulthood is inherently uncool, though, and so are the expectations surrounding it. Instead, what I’ve taken away from this character, almost half my life later, is this: Love the things and people around you as intensely and deeply as you can, and know that saying you love them isn’t as important as performing that love.

– Caitlin Goldblatt

We’ve told you about some of our fictional heroes, but what characters of page and screen captured your young hearts? Leave a comment below, or hit us up on Facebook or Twitter!