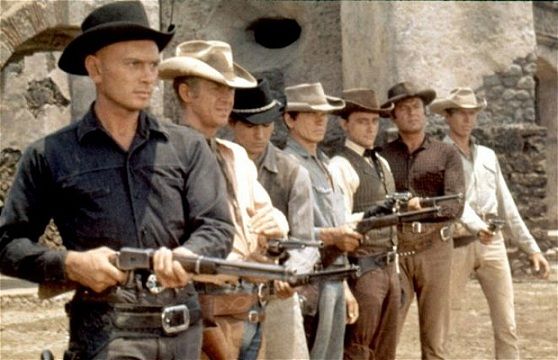

We at Deadshirt like to fancy ourselves pretty dedicated to popular culture with a combined knowledge of all things media that borders on the encyclopedic, but no one is perfect. There’s just too much music, too many films, too many comics, and way too many television episodes out there. No longer will we have to harbor the secret shame of not having experienced an expected work. Here is where we fill in the missing gaps. This week we look at the film The Magnificent Seven with Patrick Stinson…

The Magnificent Seven is an older film for this feature, but I think it represents a big gap in my personal pop culture canon. Seven Samurai, the Kurosawa classic that John Sturges bases this film on, is my favorite movie, and I’m generally interested in well-done remakes and regional adaptations. I also love Western tropes when applied to new settings, parodied, or modernized with a splash of deconstruction.

The Magnificent Seven is two hours long—a lengthy mainstream film for 1960, but actually dramatically cut down from Seven Samurai’s 207-minute running time. The filmmakers, who by all appearances were genuine fans of Kurosawa’s film, insert some kind of reference to nearly every event and subplot from the original, while adding a few of their own. The end result is a film overstuffed with underdeveloped plots.

Both films are about the same general situation. A small village is threatened by bandits, and risks starvation if they give in to their demands. They seek mercenaries to defend them, but due to their poverty, the only help they find is from seven wanderers who are moved by their plight, and so work for a pittance. It’s a marvelously simple premise that both films embellish into treatises on the social ills that led to the deadly situation in the first place.

The astonishing charisma of Yul Brynner, clearly the film’s hero, holds the whole thing together. His first scene initiates a series of deviations from Seven Samurai that make the adaptation more relatable to Western society. Brynner’s Chris demonstrates his egalitarianism when he and Vin (Steve McQueen) engage in light gunplay in order to bury a Native American in a “whites only” cemetery.

The opener makes bold social commentary, especially for 1960, and more region-specific commentary follows it. A scene that depicts Mexican farmers traveling north to the United States (their reasoning: that’s where all the guns come from) especially resonates almost sixty years later. After these earlier scenes, however, the film switches to a version of a classism motif that feels insincere. There is some nice subtext that the Mexican farmers and bandits identify more with each other than with the American gunfighters, but it receives shallow exploration.

The film alternates frequently from diligent restagings of specific Seven Samurai scenes to original sequences. The former class of scenes is actually a delight, because the camera always finds a new angle or approach. For instance, the “tag-along” character (Mifune’s Kikuchiyo in original, Horst Buchholz’s Chico in this) catches fish with his hands in both versions after the others refuse to feed him, but, when his continued presence is revealed, Kikuchiyo boldly leaps in front of the others, while Chico calmly roasts his fish and waits for them to stumble upon him.

The wholly new scenes and characters justify The Magnificent Seven as more than just a cultural translation. Sturges has combined several of the major samurai characters (Chico is equal parts Kikuchiyo, the wild one; and Katsushiro, the young one), creating new blank slates in the “seven” to work with. Thus, the film showcases some Western archetypes in Lee, the traumatized cutthroat; Luck, the amoral fortune hunter; and Bernardo O’Reilly, the half-Mexican who finds himself identifying with the villagers in spite of himself. Sadly, these characters still get short shrift.

The most laudable—yet problematic—addition is the elevation of the bandit leader to being a named character. Eli Wallach’s Calvera replaces horror with intrigue; while the bandits are no longer faceless killers, they are capable of manipulating the villagers against their protectors. Calvera makes many mistakes throughout the film, but the script justifies them with the intense kinship he feels with the American gunmen. The farmers are part of his world, but he does not respect them. In contrast, the Americans fascinate him, but he ultimately proves unable to understand them. The film ends when the American gunmen paternalistically overrule the farmers, who are not only their employers but also the ones whose lives are at stake. It only sort of works because Calvera’s intensely abusive relationship with the village leader leaves no doubt that to leave the farmers under Calvera’s control would be to let them suffer terribly.

There’s a lot to love in The Magnificent Seven, even for a nit-picky Kurosawa buff like me. However, the very genre the film epitomizes also constrains it. Sturges removes much of the bite of its source material, with young lovers reunited, men finding closure in their dying moments, and vengeance being righteous and cathartic rather than grotesque and empty. For better or for worse, the meaning of the final scene changes. While the content is similar in both versions, Seven Samurai represents a final, baffling failure of communication between the different layers of society, dooming them to their old destructive patterns. The Magnificent Seven ends more optimistically, as if to suggest that, one day, people will no longer need strongmen to live their lives in peace. Perhaps the latter message holds more relevance, however, by indicating that the few who only thrive on conflict may fade away and that the next generation still has time to avoid this breakdown.

Interesting points.

I think Calvera was the best thing about that movie, and he had, what, five scenes?