Everyone has an album that has stayed with them for years, even decades, a constant musical companion that grows with you as your life and perspective changes. With that in mind, Deadshirt presents Perfect Records, an ongoing series of personal essays about the albums that stuck with us and how they’ve shaped our lives.

It’s 2006, and I’m a junior in high school. I’m sixteen, five feet tall, and weigh barely a hundred pounds. It will be months before I share my first kiss with a Russian girl named Maria in front of the principal’s office between second and third period. By then, I’ll have rapidly and mysteriously grown four inches, and my voice will have dropped half an octave.

But right now, I’m sixteen, I’m short, I’m frail, and while I’m not bullied or tormented, I am angry. I smile a lot, and laugh, and tell stupid jokes, and bang my head against walls when I realize just how stupid they are. I’m well-liked, maybe even respected by my peers, and loved by my close-knit crew of musicians and comic book nerds.

Some of them are starting to date. My best friend takes me aside to tell me that, a few weeks earlier, he’d lost his virginity to his girlfriend. He describes it as an awkward, rotten experience, and he’s not so much bragging as he is confiding in me, his brother. I hate him so much.

Today, like most days, we wander the halls during lunch and goof around with casual friends, and the girls smile and flirt, but never with me—I’m certain of it.

In 2011, after a bad breakup, my friend flips through our high school yearbook and points out a half-dozen girls who he knows liked me, but I could never see it. He thinks he’s helping, building up my confidence, but all I can do is get angry at myself.

Back in 2006, I put on a pair of around-the-ear headphones and flip on my cheap 2GB mp3 player to the first cut on Whatever and Ever Amen, and dream of being somebody.

“Now I’m big and important

I’m one angry dwarf and

One thousand solemn faces are you

If you really wanna see me

Check the papers and the TV

Look who’s tellin’ who what to do

Kiss my ass

Goodbye”

– “One Angry Dwarf and 200 Solemn Faces”

A lot of labels used to describe music are kind of bullshit. Ask five music fans to define “indie rock” and you’ll get five very different answers. Some alleged subgenres are even more blurry. Think about the term “geek rock,” and the acts you’ll find under that umbrella: They Might Be Giants, OK Go, Fountains of Wayne—what the hell do these bands have in common with Harry and the Potters, or even with each other? On paper, it’s nonsense.

But consider what comes to mind when you think of the label “rock star.” Rock stars are sexy and larger than life. Ben Folds is not. He’s a doofy-looking guy with thick glasses. Nobody’s going to pick him out of a crowd and say “that guy’s a singer in a band!” Yeah, “geek rock” is a vague, ill-defined, ultimately meaningless term, except—like shrugworthy, unsexy pornography—you know it when you see it.

By the time I was sixteen I knew I was never going to be a rock star. I was a singer-songwriter, a good one for my age, but I was at best average-looking. I was nobody’s idea of a sex symbol. So, as a dorky teen in glasses and baggy clothes, I latched onto a peer. The way Paul McCartney saw himself in the bespectacled Buddy Holly, I saw a future for myself in the Ben Folds business.

It’s December of 1982, and Ben Folds is sixteen. He’s sitting in the waiting room of a clinic in North Carolina while his girlfriend gets an abortion. He knows it’s the right thing to do. He doesn’t believe that it’s evil or sinful, and he knows it’s not his decision to make. That doesn’t mean he can’t feel guilty.

“Can’t you see, it’s not me you’re dying for.”

– “Brick”

It’s March of 2009, and my college girlfriend and I are doing something stupid. It’s passionate and exciting and entirely unprotected. We walk around with dumb, shit-eating grins on our faces for the next few hours, as we meet up with our friends from writers’ workshop, who wonder why we’d missed class. We don’t tell them, but they can easily guess at least part of the story.

Later that night, my girlfriend remembers that she’d just switched birth control, and that’s when we stop laughing about it.

It’s three weeks later, and she’s, well, late. We spend the next two weeks tense and detached. We have a talk, and I start thinking of ways to make $400 disappear from my savings without my parents noticing.

(In 1982, Ben Folds is at a pawn shop selling all his Christmas gifts.)

When my girlfriend finally gets her period—thrown off, she figures, by her change in birth control—the relief is palpable. We come out of the ordeal closer than ever.

Back in 1982, Ben Folds and his girlfriend aren’t so lucky.

It’s 1996 and I have no idea what this song is about.

It’s 2015 and I am grateful that I still don’t.

Ben Folds Five describe themselves as “punk rock for sissies.” It’s a label that’s stuck around for the life of the band, even after they more or less threw the “punk” part out the window. They’re a modified power trio—there’s Darren Jessee on drums, Robert Sledge on bass—but in place of rhythm guitar, there’s a tiny man pounding on a grand piano. You hear that punk rock side of them best on “Song for the Dumped,” which is about as angry as the band gets. The “sissy” part doesn’t just refer to the lack of guitar, but to the fact that every pissed-off turn of phrase seems to be followed by a wink and a smirk.

When they were just starting out, there was pressure for the band to play lounges and coffee shops, the kinds of places where piano-fronted acts are expected to play. That wasn’t for them, at least not yet. Ben Folds Five set themselves apart by playing where they weren’t expected: at punk bars and rock clubs. They might get a raised eyebrow during sound check, but by the time they were done playing, everyone would know why they were here.

It’s unlikely that self-respecting punk would apply the label to Ben Folds Five, but at the very least, the band makes you question why Wikipedia automatically redirects “Piano Rock” to “Soft Rock.”

It’s 2006, and I’m in love—or what passes for love when you’re seventeen and a very, very late bloomer. We’re sitting in the hallway where we eat lunch, and having a very matter-of-fact type conversation about our relationship. I’m voicing a little frustration. Her mother doesn’t let her date, especially not Americans, so we’re stuck making out in stairwells and corridors. We’ve seen each other outside of school grounds exactly once, at a Halloween party, which was only accomplished by leaving out some key facts (such as “I’m her boyfriend”) to her mother.

At some point in the exchange, I say “…and I’m not saying we should break up or anything.”

And Maria smiles and replies, “It’s alright, we can if you want.”

“But you just smile like a bank teller,

Flatly telling me ‘have a nice life.”

– “Selfless, Cold, and Composed”

I am dumbstruck. This is my first love, this sacred thing that television has taught me I will cherish for the rest of my life, and she’s just shrugging it off like it’s nothing. Why can’t she see how important this is? Why is she treating this like we’re just two awkward teens casually hooking up during lunch periods? What is wrong with her?

Whatever and Ever Amen came about during a unique period for rock music, when alternative rock got mainstream attention and the weirdest variety of music was getting played on Top 40 radio and MTV’s Total Request Live. The week “Brick” peaked at #17 on the Billboard Pop charts, Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On” was in the midst of its endless reign over the music world. Also in the top twenty: Savage Garden’s cheesy ballad “Truly, Madly, Deeply,” The Backstreet Boys’ “As Long as You Love Me,” Matchbox 20’s jangly soft rock number “3 AM,” and Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn.” Compared to today’s dance-happy radio, 1997 seems depressed. In 2015, pop music is a clear-cut genre. In 1997, it was a title, an achievement. That’s not a value judgement—today the internet makes it easier for everyone to key on the specific kind of music that they like, but what’s been lost is the kind of wacky tossed musical salad that allowed someone like Ben Folds to become a household name, and a dead baby funeral dirge like “Brick” to become a hit song.

Whatever and Ever Amen is not a “pop album” in the way we think of that term today, in fact, it sort of defies genre altogether. It’s a hodgepodge of different musical sounds that are held together by a distinct voice and instrumentation. “Kate” is a light, poppy love song; “Smoke” is sad and singer-songwriter-y. And then there’s “Steven’s Last Night in Town,” which is accompanied by an honest-to-god klezmer band.

It’s an album recorded mostly live in a rental house and doesn’t sound particularly polished or produced. There’s a moment in “Steven’s Last Night in Town” when you can hear the house phone start ringing. It’s timed perfectly with a silent moment on the track, so it stands out glaringly. Someone can be heard laughing at the freak occurrence as the band kicks back in. Whatever and Ever Amen, in hindsight, feels more like an album that you’d download from someone’s Bandcamp page than you’d hear on the radio. It’s a product of a mass musical culture that we’re unlikely to see repeated, when a dorky-looking guy with a not particularly stunning voice could be a pop star, even for a short time.

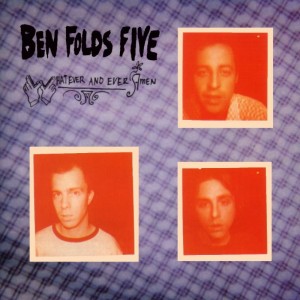

It’s 1997, I’m eight years old, and I’ve probably listened to my CD of Whatever and Ever Amen a hundred times. It’s a promotional copy, so instead of a jewel case it’s stored in a plain white cardboard sleeve with a white sticker on it; it doesn’t even have cover art. It’s fun, it’s weird; it’s got a lot of piano on it, and my mom’s teaching me how to play, and I can sort of figure out some of the easy parts by ear.

There are some songs I skip. I like the fun ones, like “The Battle of Who Could Care Less” and “Kate,” but the quiet ones just make me sad, so I usually don’t even play the last few songs. My older sister tells me I’m missing out on the best part, but I know what I like and I’m happy to keep listening to it again and again. I don’t have room for this sad stuff in my eight-year-old head. I want to dance around and play with my Star Trek figures.

It’s 2011, and I’m playing “Evaporated,” the closing track off of Whatever and Ever Amen, in front of a crowd of my college friends during my last show before graduation. I’m playing the student-run coffee shop, a place where you can sort of get away with playing sad songs if you’re good at it. I’m good at it.

“Blind man on a canyon’s edge of a panoramic scene

Or maybe I’m a kite that’s flying high & random, dangling a string

Or slumped over in a vacant room, head on a stranger’s knee

I’m sure back home they think I’ve lost my mind.”

– “Evaporated”

Like so many of the songs I’ve come to consider my favorites, “Evaporated” is soft, beautiful, and heartbreaking. It’s a song about not knowing your value or purpose, feeling aimless and weightless and vulnerable. I know the stories behind most of the songs on Whatever and Ever Amen, but not this one, and I don’t want to. This one is mine. All I need to know about “Evaporated” is that, once, some sad near-sighted bastard felt lost and worthless, turned that feeling into music, and now some other sad near-sighted bastard he’s never met is singing it like it’s his.

He made it.

If you enjoy Perfect Records, consider contributing to Deadshirt’s crowdfunding effort on Patreon, and check out other entries in the series!