It was hard for me to know what to expect from The Martian. The book had been described to me—in a not entirely pejorative sense—as “engineering porn.” I wasn’t an enormous fan of Ridley Scott’s last sci-fi epic, Prometheus. I felt like I’d seen Matt Damon rescued enough times. But I couldn’t argue with the cast they’d assembled—Chiwetel Ejiofor, Donald Glover, Michael Pena, and Sean Bean all being favorites—with a screenplay by Drew “Cabin in the Woods” Goddard? Sold.

I had the best time in the theater I’ve had in a long time.

The Martian is a film with no violence, yet it is packed with tension and high drama, leavened with a gentle wit that yields some of the best laughs of the year.

The premise of the film does the heavy lifting—an astronaut is stranded on Mars and must survive till help arrives. Everything else comes from answering the questions “how will he survive” and “how will NASA rescue him?” The structure facilitates a diamond-hard sci-fi approach that even satisfied notorious nitpicker Neil DeGrasse Tyson. The movie makes no bones about the following inconvenient facts that Hollywood typically ignores—it’s hard to accelerate in space, it’s hard to lift things out of a gravity well, and there’s nothing on Mars that will help keep a human being alive.

Matt Damon does a superb job of playing Ares mission member/botanist Mark Watney—he confronts his plight with good humor and inventiveness, treating every moment he remains alive as a blessing and narrating it to his camera for some future expedition to find. He’s an idealized protagonist, which is fine for this kind of movie, because he’s what every engineer and armchair engineer wishes they could be. The emotion in his triumphs and successes is felt by the audience (in- and out-of-universe) as nothing more or less than as a surrogate of humanity. Well-worn space movie tropes like his grieving family at home or his regret for past mistakes are thankfully eschewed. Goddard understands that the book didn’t need such additions.

The thriller side of the movie comes from the efforts of NASA, both on Earth and in space, to rescue Watney without committing an expensive bungle and killing him on semi-live TV. The darkest this movie gets is early on, when you can see the temptation on the face of Jeff Daniels’s head of NASA to let Watney die quietly, peacefully, out of view of the public: a silent sacrifice to save the space program. But once the information is released, the world shows its readiness to solve the vast physics problem that feeding and retrieving Watney represents. The film is understated but firm in its confidence that this is about more than saving one person, worthy though he be. It’s about the resolve of humanity to spread its wings, and they didn’t need to drag out that Kennedy speech to tell us so this time.

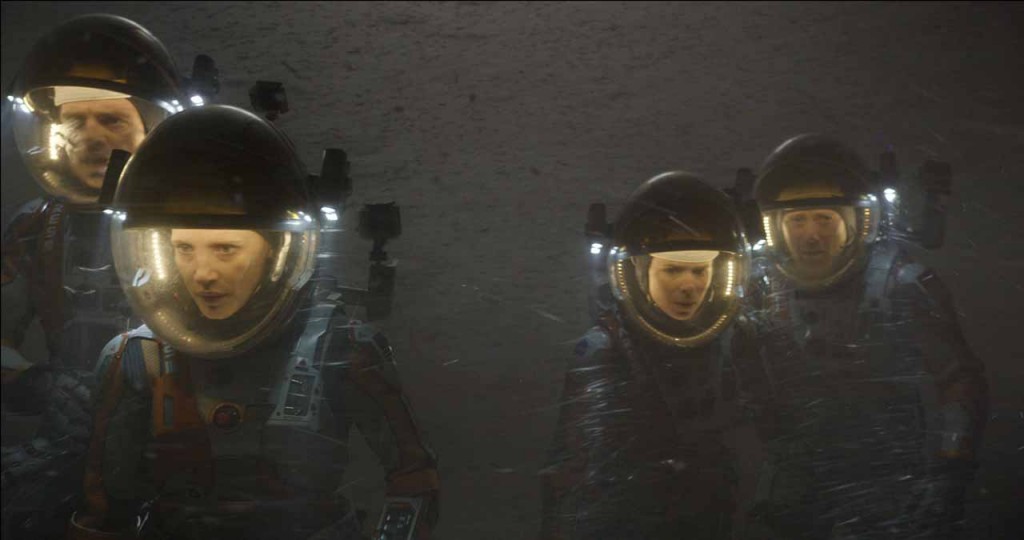

The movie is kept from stagnating (“will Watney manage to ration his food X more days?”) with some genuinely clever late twists. One of them I like to call the “anti-Star Trek moment,” in which devil-may-care recklessness that would pay off in every other space movie ever made backfires and nearly dooms Watney. It goes to show how seriously the author and filmmakers respected the NASA approach of caution and redundancy, even moreso than their own fictional characters. The other is the “Star Trek moment,” when a brave crew defies the odds and orders in the name of camaraderie. This sole moment of melodrama makes the third act, throwing into sharp relief the clockwork rationality of the rest of the film while never breaking immersion or scientific plausibility.

I keep alluding to the scientific accuracy of the film, and it really does bear appreciation. While the ships and facilities in the film are futuristic and extensive, they do not rely on a screenwriter’s conceit to violate known physics. As far as I’ve been able to tell, the single least realistic sequence in the film is agreed to be the threat of a sandstorm knocking over a spacecraft, as the air is too thin on Mars to create that kind of local force. So, they did their homework and then some.

But don’t go for the physics, go for the characters. Damon’s performance has been praised more thoroughly and literately than I can manage. What I would like to highlight is both the acting and the writing for the film’s female characters. Kristen Wiig plays a stone-faced, professional NASA public relations chief with all the intelligence and energy called for—I’d like to see her in more dramatic roles.

Jessica Chastain takes a potentially thankless part of “leave no one behind” expedition commander, and with her eyes alone transforms it into a layered character balancing concern for one part of her crew with that of another. Mackenzie Davis is a surprise standout as the low-ranking satellite technician who discovers Watney’s still breathing, and rises up the ranks at NASA with her concern and resolve. And Kate Mara is an absolute pleasure as the ship’s technician, in both a true-to-life and positive representation of a female “nerd.” Only one of these characters is given a romantic subplot, and even that is refreshingly understated. While this is a film built around male charisma and a large number of male characters, the female characters are Very Very Good, and display utter professionalism and competence. While this is inherited from the source material, the fact that Hollywood resisted the temptation to hook someone up with Matt Damon or have someone burst into tears is a good sign for the future of big budget sci-fi.

The Martian is the best entertainment that could happen to the space program, and maybe to the human spirit, right now. Without preaching, it reminds us to look upward and outward. It examines cynicism and then rejects it, not out of principle, but because it has failed to be of use. There is going to be a bumper crop of young scientists and engineers writing in their college admission essays how this movie inspired them. It is only appropriate that Ridley Scott, who gave us the dark beauty of Alien so many years ago, has now lent his talent to its antithesis.

The Martian is now playing.