Fans can argue forever about which bands are the greatest, or what makes a band great in the first place. Music, like painting or cooking, is a craft for which analysis and study can only get you so far – sometimes what makes music good can’t be explained, it can only be experienced. A great musical act can’t be manufactured from a blueprint or a recipe, hard as it’s been tried. But I think we can agree that great bands and artists often share certain ingredients, and there are some attributes that they just have to have in order to be great. Not every band can have the whole package, but certain qualities are just important, some more important than others, depending on the genre of music.

It’s impossible to break down exactly what makes great music great. But fuck if we don’t try anyway. To that end, consider this Musical Food Pyramid.

The Musical Food Pyramid is built on two assumptions: that certain ingredients make for great musical acts, and that you don’t need to have all of them to be great. Some ingredients are more important than others, and the proportions vary between different genres and sub-genres of music. But this is still a pyramid, meaning that the closer to the bottom you get, the more essential that ingredient is.

So let’s start at the top:

PRESENTATION

To use our food pyramid metaphor, presentation is the sugar and spice of popular music, though not the substance. It’s not necessarily good for you, and it can’t make a lousy act good, but it can make a good act better and more exciting. The genres that lean most heavily on presentation are top 40 radio pop, rock and hip-hop. They may use gimmicks, costumes and dance moves, sometimes to enhance but more often to distract from lackluster music. Presentation-driven acts are often better known for their music videos or outrageous live shows than their songs.

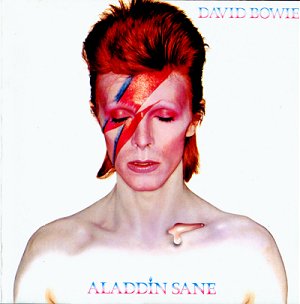

If an act is already solid musically, and has strong foundations in the bottom layers of this pyramid, then a flashy presentation can make the experience extra sweet. Lots of classic artists got attention due to command of presentation. Motown soul groups performed on television with synchronized dance moves that became almost as timeless as their songs. Pink Floyd never lacked for strong craft or musicianship, but became best known for their innovative use of light, sound and props in their stage shows. David Bowie, Madonna and Lady Gaga may never have pop sensations if not for their dramatic, constantly-mutating public personas.

Presentation often defines an act’s connection to a genre, or even a genre itself. Sometimes the difference between a group being considered alt-rock or punk is a haircut or a tattoo. A lot of bands use their look as a way for audiences to imagine what they might sound like before they even start playing. This can be a double-edged sword, however, because failing to live up that imagined sound or to present the right attitude can get you labeled as a poser. (But we’ll get to that.)

DISTINCTIVENESS

Let’s face it: there are WAY too many bands. Even after you weed out the ones who aren’t skilled or interesting, there are just far too many acts out there, and so many of them sound the same. For every band that makes it, there are a thousand who are as good or better that no one ever hears. Some bands stand out from the pack through a presentation gimmick (arguably the cheap way) but the most obvious solution is still the best: just be different.

An act doesn’t have to invent or reinvent a genre to be distinctive, it just has to have something, or some combination of things, that other acts don’t have. Maybe it’s a specific guitar sound – nobody sounds like Tom Morello but Tom Morello. Maybe the vocalist is unique and recognizable – Janis Joplin was the only person on Earth who sounded like Janis Joplin. Maybe it’s an unusual instrumentation – Ben Folds Five is an alt-rock band with no guitars; Apocalyptica is a metal band made up of only cellos; Dropkick Murphys are punk with bagpipes.

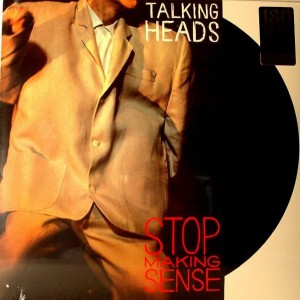

But in the best cases, what makes a great band distinctive is indefinable. Talking Heads are just weird. They’re fun but discordant, they write about unusual subjects and break from conventional sounds and arrangements. There’s a quirkiness that can’t be imitated, a specific attitude even if you discount the lyrics. Covering a Talking Heads song is almost impossible without doing a David Byrne impression, because his cadence and style is soaked into every phrase.

You just know a Bruce Springsteen song. He writes in a variety of rock and folk subgenres, but you could listen to any band cover one of his songs and in the back of your mind you can just tell, “this is sounds like a Bruce Springsteen song.” Great songwriters have signatures that sometimes elude description, and you can hear them in the acts they influence. In the case of Bruce, you hear him in The Gaslight Anthem or The Hold Steady.

And you can always tell when a group grew up listening to They Might Be Giants.

PROFICIENCY

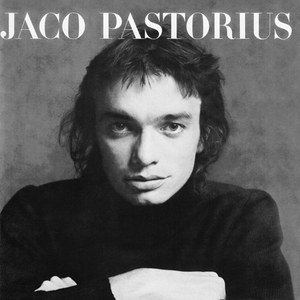

This one’s pretty self-explanatory. Obviously, one of the best ways to impress an audience is to be good at what you do. You don’t have to like jazz fusion to be amazed by Jaco Pastorius’s bass playing. He could make sounds that you wouldn’t believe could come out of a bass guitar. You don’t have to like metal to appreciate an incredible drummer or a crazy-fast guitar player on an intellectual level. Being a technically-great singer, player, rapper, or producer should be enough to gain at least some recognition, and there’s no reason to waste much time explaining why here. It’s probably better to just move on to why proficiency is not enough:

AUTHENTICITY

This one’s got a lot of layers, but in the end it comes down to answering one question: does the audience believe the performance? That’s why authenticity carries a heavier weight than proficiency on this scale. Again, a technically perfect performance can intrigue you on an intellectual level, but music is an art, not a science, and ultimately matters is heart, not head.

An authentic performance is informed by feeling and personal experience – it’s how an artist connects with their audience on a gut level.

Great genuine performances often come directly from personal experience, from an artist telling his or her or their own stories from the heart. A personal story can be extremely powerful, grant a listener a new point of view, or even profoundly affect someone’s life. Childish Gamino’s “Outside” reflects on rapper/actor/comedian Donald Glover’s childhood and and the way his family struggled to make a better life for themselves, even as that alienated them from where they came from. It’s a very specific, very personal story about poverty, race and identity, and for many listeners, it may reflect their own struggles, but even if it doesn’t, it’s too compelling and heartfelt a story not to elicit an emotional response.

Life experience definitely informs an artist’s compositions and performance even if it the work isn’t autobiographical. Not many artists can get by just telling story after story from their own lives – most people, even pop stars, are not that interesting. Authenticity often shines best when artists translate their own feelings and experiences into more general ones. Listeners prefer to hear a song that they can believe is about them, leaving artists with the challenge to tell stories that are personal, and yet about anybody.

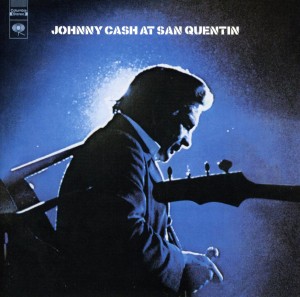

Johnny Cash never did time in Folsom Prison, but he did feel isolated and depressed, and he turned that into a compelling song about serving a life sentence in one America’s cruelest penitentiaries. “Folsom Prison Blues” captured that desperation, but it wasn’t just a hit with hardened criminals. The door swings both ways – Cash told a specific story based on a genuine but universal feeling, and listeners could translate it back into its raw emotional form. It’s not your story, and yet it is, because you’ve felt that same feeling that the speaker, and the artist, are feeling.

Bruce Springsteen will never have to worry about money again for as long as he lives, but his last album Wrecking Ball was a series of furious anthems riling against the bankers and politicians who brought about the recession, mostly from the perspective of the working poor. He may be a rich bastard now, but his background as a South Jersey hillbilly gives him the experience to articulate their troubles with much the same authenticity as he did with 1978’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, written when the Boss himself had still yet to see a dime for his music. He remembers his roots, or at the very least is terrific at convincing audiences that he’s still a blue-jeans-and-white-t-shirt man at heart.

Authenticity also includes the all-important “cred,” which is very difficult to measure because you earn or lose cred very differently depending on the genre of music. In pop, you get cred by winning awards, TV contests, or breaking sales records. In hip hop, you get cred by flaunting your financial success, while in punk rock you must hide that success, or better yet, never have any. Gangsta rappers and outlaw country singers gain cred by getting shot or stabbed. At the dawn of blues, nothing earned you cred more than a history of real human suffering. (You’ll note how little any of this has to do with the music.)

A lack of authenticity can be sniffed out instinctively. It happens a lot in pop music, when you can just tell a singer is just a pretty face or a set of slick dance moves, when the lyrics are just “put your hands up, everybody dance.” There’s no personality there. In rock it can occur in two opposite ways: either a band “goes pop” or “goes country” when they’d previously been rootsy or punk, or they try to repeat their early success over and over despite growing up. Either way, they come off as shallow. (Weezer should stop releasing songs about partying all night. You’re over forty now, Rivers, you must have a real life to sing about.) There must be some real or perceived connection between an artist’s life and their art, or no one will be able to connect it to their own lives.

Don’t ask for an explanation for The Decemberists, though. Somehow those guys can write songs only a teenager could relate to emotionally in language only an English professor can understand and still come off as 100% real. It must have more to do with that last, most fundamental category…

SONGCRAFT

Got an open heart, a powerful voice, a stand-out sound and a kinetic stage show? Great.

Now play me a song.

The legacy of a great artist is his or her songs. Songs are the product. They’re the moments their fans hold their breath waiting for. Dressing up like the band won’t make you one of them, you can’t sing along to an extended jam break, and if you’re just looking for a good story there’s a dozen other ways you can absorb one. It’s chords, melody and lyrics. It’s hooks and build-ups. It’s that predictable but satisfying breakdown before the last chorus kicks in.

A great song is great no matter who performs it, whether it’s a gal with an acoustic guitar, or a group of kids with synthesizers or a string quartet. Even if it’s performed poorly, you don’t say “this song is awful,” you say “this guy is butchering a great song.” You know a song is great the first time you hear it, and you could go five years before hearing it a second time, but when you do, you still recognize it. It’s the one that you’re still singing in your head after a show even though there were two other bands in between and you only know the words to half of the chorus.

Without a great song, nothing else matters. It’s not the only thing that matters, just a great song won’t do the trick on its own, that’s what the rest of the pyramid is for. But it has to be the foundation upon which everything else is built, otherwise who cares? Songs are what audiences go out to see and what they take home, and without them, nobody’s going anywhere.