Science fiction plucks from within us our deepest fears and hopes then shows them to us in rough disguise: the monster and the rocket.

-W.H. Auden

That epigram adorns the script to Alien, a single-sentence summary of what makes great science fiction work. While we all love poring over technical manuals and expanded universe guides (Right? Don’t we all? Guys?) every great science fiction work is a metaphor wrapped in aluminum foil. Scientific pedantry is a niche interest, so popular science fiction has to speak to something people can relate to. Finding this center is hard enough to capture attention in a 30-second pitch for a screenplay or a book, but attempting to incorporate it into music is like juggling chainsaws. Sci-Fi music has two directions it can go:

- The Prog-rock route of lush and impenetrable 12-minute songs about the howling cyber Valkyries of the syntho-tombs out beyond LaGrange point 5.

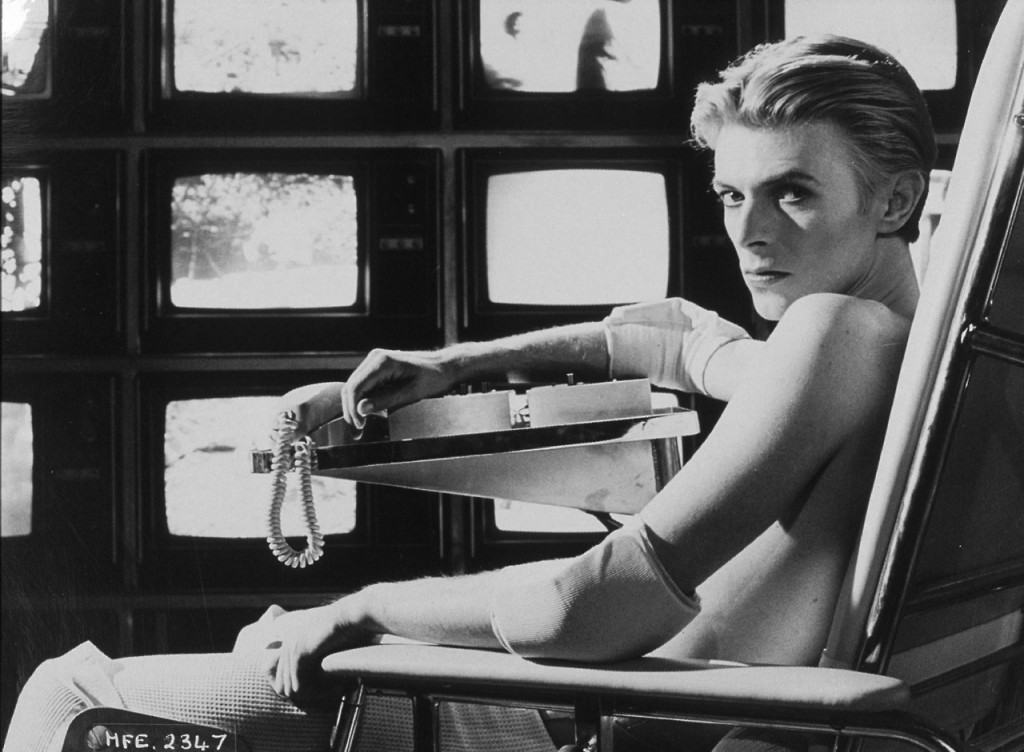

- The sonic b-movies of David Bowie.

I’ll take the man with the lightning bolt on his face catching the chainsaws, please.

David Bowie’s legacy starts with science fiction. “Space Oddity,” his first successful single after a string of novelty flops, played off the title of one of the most popular science fiction movies of all time. Its release in July of 1969 coincided with the first manned moon landing and was only stocked on shelves after the successful return of the Apollo 11 crew. It’s not hard to understand why this song about the most important space mission of all time named after a blockbuster movie captured the zeitgeist, but otherwise “Space Oddity” may never have found its time in the spotlight. When was the last time you cranked up the radio saying “Oh man! Finally, a song about an astronaut! Who dies! And a guy literally refuses to tell his wife that he loves her!”? “Space Oddity,” like its more John Hughes-friendly catalog-mate Changes, has a certain transparent element that lets the listener layer it over his or her own apprehensions about life and find it apropos despite the fact that it is an over-five minute song that features a fake rocket launch and Rick Wakeman, which would normally damn it to the blacklit D&D basement where we keep Prog.

Hey, prog fans, come back, there’s weed around here somewhere. But seriously folks- The real reason the song endures is that David Bowie is fucking terrified of dying. And the end of the world. And getting old. And Iggy Pop’s childhood. Here’s a quick list of other songs about David Bowie being scared:

- Five Years

- All the Young Dudes

- Oh! You Pretty Things

- Ziggy Stardust

- Rock n Roll Suicide

- Panic in Detroit

- Ashes to Ashes

- Cracked Actor

- [The sound of Julian bringing this listicle to a halt]

Sorry, it seems I’ve just started listing David Bowie songs endlessly again, let me take two of my Ziggitor® to calm down [He’s just snorting crushed up smarties –Julian.] With the exception of “Cracked Actor,” those are all Sci-Fi songs, friend. “Cracked Actor” is a song about an old dude trying to buy a young gay prostitute, so that’s more of a political thriller. Ba-zing! Bipartisan Bowie Burns for all. What I’m driving at is that by embracing the “Deep Fears” aspect of science fiction and making the music itself simple, the Thin White Duke managed to strangle some broad pop hits from the throat of very personal inner demons and construct compelling alternate realities.

Beatles vs. Stones in ’63, Marc Bolan (and T. Rex) vs. David Bowie in ’73. The main men of glam maintained a friendly rivalry built over an important dichotomy: Bolan looked into myths and found magic, while Bowie looked into the future and saw the apocalypse. Bowie’s breakout album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars starts with “Five Years,” a waltzing look at the world after it’s announced on television that earth has five years until Ragnarok.

Four chords, it’s a first-day-on-guitar kinda song if you can nail the timing. As the piano becomes more frantic and hammering the drums continue with plodding precision, giving one the impression of the singer walking in slow motion through town square as civilization collapses under the weight of its death sentence. There’s tears in the streets, fights break out, little ambiguity is left about the impending disaster by these lines:

News guy wept and told us

earth was really dying

Cried so much his face was wet

then I knew he was not lying

This is the most direct reference to looming universal doom on Ziggy, I won’t Pixar-theory you to death about the immense and ever-changing mythology that Bowie released in drips and drabs through the years to bind together the album’s ten original compositions. Most importantly, “Five Years” serves as a sort of thesis statement for the rest of the Ragnarok-centric early 70’s work that used cocaine and the paranoia of sudden fame to spin radio friendly cotton candy. The Five Year termination date came to him in a dream, Bowie said. The ghost of his father told him he would die in five years, and to never fly again.

Even I find it comically narcissistic to use your own death as a sell-by for the rest of the world, but Bowie took the deadline seriously and in the process of avoiding air travel he wrote a song that sounded like Roger Corman and Russ Meyer drunkenly taking a go at “Earth Angel” called “Drive-In Saturday.” The triumph of “Drive-In Saturday” rides on the same concept as taking a spoonful of sugar with your medicine, helping a tale of post-nuclear war sexual impotence slip in your brain by cranking the schmaltzy doo-wop vibe up to eleven. It’s another waltzing slow dance number, pumping up the tempo from the occasionally dirge-like “Five Years” and swapping strings for saxophone arrangements that call back to Bowie’s original aspirations to play sax in Little Richard’s band.

You can almost make it all the way through the song thinking you’re hearing standard teenage lust in ¾ time, but then-

It’s hard enough to keep formation

amid this fallout saturation……With snorting head he gazes to the shore

Once it raged a sea that raged no more

I seriously, honestly, will give you ten dollars if you’ve got a classier way to say “The nuclear war killed all boners.” Justdandy@deadshirt.net, I’m a man of my word. The inspiration for this one can be tracked back to some domes spotted out the window of his train during his first tour of the US, which quickly spun into this DiS mythology of a sexless wasteland where people live in protective domes and have to watch videos to remember how to bone. Of course, you could play this at a junior prom for a slow-dance and nobody would be the wiser due to the fact that it’s a stone cold groove. Much like Star Wars, whose success rests on charming characters and iconic visuals and whose imitators latch onto niche interests like galactic politics and weird names, “Drive-In Saturday” is as accessible as it is personal.

It’s with this in mind that we can start to decipher maybe the most famous and the most oblique of Bowie’s songs about the apocalypse, “All The Young Dudes.” Best recognized recently from its appearance in Juno, AtYD was a gift to Mott the Hoople from Bowie to try and keep them together, and was composed somewhat contemporaneously with “Five Years” and the rest of Ziggy Stardust in 1972. Widely regarded as a paean to youth, sexual liberation, and hot eyelinered up guy/guy action in the glittery gutters and thrift shops of ‘72 London, the anthemic chorus is almost impossible not to sing along to. Taken on its own and without Bowie’s statement in an interview with William Burroughs in Rolling Stone a year later that it’s about the apocalypse (I know, that’s cheating) the slinky lyrics show little clue of the sobering truth. Putting it next to “Five Years” like a Rosetta Stone helps us divine the truth, especially in these selections from the first verse:

Wendy’s stealing clothes from unlocked cars

And Freddy’s got scars from ripping off the stars from his face……Television man is crazy saying we’re juvenile delinquent wrecks

I need a TV when I’ve got T-Rex

The same chaotic breakdown in society is evident as in “Five Years,” as is the place of the media in maintaining the hysteria about the impending doom. The poppier execution more effectively cloaks the meaning but these trademarks of Bowie’s paranoia are amplified in this live version where it’s put together in a medley with “Oh! You Pretty Things:”

“Oh!” wears its science fiction influences more on its sleeve with mentions of the World to Come and the Homo Superior, but once you hear the similar descending bassline chorus that earworms its way in then you start to understand just how pervasive the idea of total annihilation was. The full song’s second verse features more mentions of the news and even “strangers,” not dissimilar to the “Strange ones in the domes” from “Drive-In Saturday.”

“All The Young Dudes” is by far the most popular of the songs we’ve analyzed in this article while also being the hardest to decipher and find the sci-fi doomsday meaning of. Considering these works as a whole paints a picture not just of a cursed future, but of the man who looks out his window and can’t help but see the world circling the drain. David Bowie plucked out his deepest fears and put them in the rough disguise of the monster, then put the monster in stack heels and set it loose on the unsuspecting airwaves.

One thought on “Future Songs of Lonely Little Kitsch: David Bowie and Science Fiction”

Comments are closed.