Film is an entertainment medium that, by its very nature, tends to reward the viewer in rewatch. Sometimes movies even reveal to us how we’ve grown or changed since we last saw them. Our own Max Robinson reassesses old favorites, seasonal classics and the occasional oddball lost under the couch in his monthly column, Stale Popcorn.

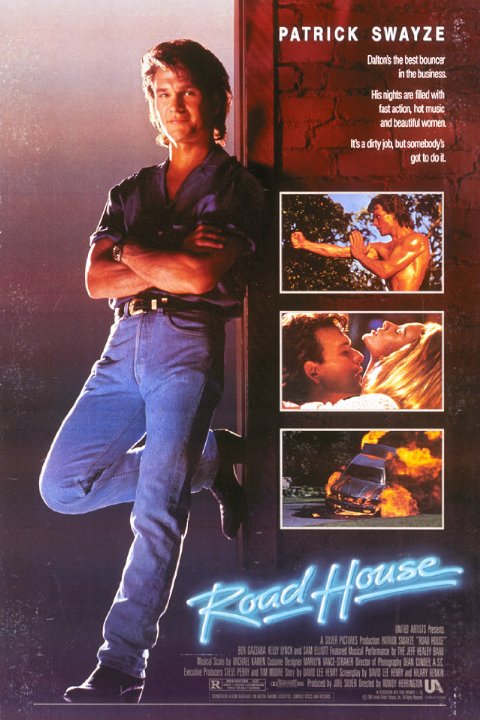

1989. Before it was a Taylor Swift record, it was the year that gave us Tim Burton’s Batman, Do The Right Thing and, hallowed by thy name, Road House. Rowdy Herrington’s tale of a savage Missouri town and the one man bold enough to tame it is as great as it is inexplicable, which is to say: real great. It’s one of those movies I delight in watching with good friends or introducing to people who only know it from the selected lines of dialogue that are embedded in the Source Wall of popular culture. What I find really interesting about Road House is how, despite its rep as a Guy Movie, a lot of people I know who are *really* into it are women or unaligned with the cisgender binary. Beyond Patrick Swayze’s immaculate abs and male-mom jean butt, what keeps us coming back to this movie? Simply put, I think it’s this:

Road House is, at its core, one man’s uneasy attempt to reject toxic masculinity.

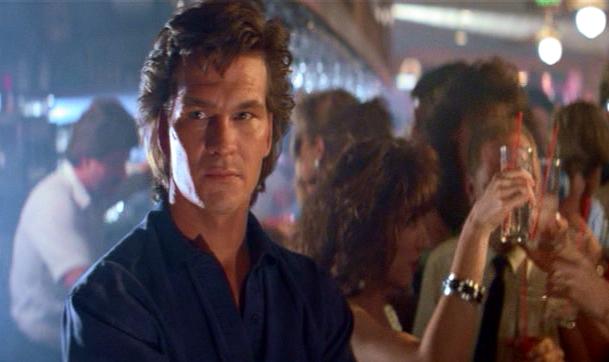

There’s a perfect Eighties scumminess to Road House. When we first see The Double Deuce, the movie’s titular road house, it resembles a bacchanalian hellscape. Chris Latta‘s unnamed bar patron lasciviously pimps out the honor of feeling his girlfriend’s breasts to strangers; mindless violence breaks out at the slightest provocation; a waitress/coke dealer angrily scolds her customers for trying to score from her outside the bathroom. Standing solitary, apart from the grotesquerie, is Patrick Swayze’s Dalton.

Let’s consider Dalton, a man whose reputation as a “cooler” (kind of an alpha-bouncer) brings him to Jasper, MO, at the behest of desperate Double Deuce proprietor Frank Tilghman. Throughout Road House, the audience comes to know Dalton’s laid back outlook on life through a series of zen quips. Whereas the “40 year old adolescents and trustees of modern chemistry” that hang out at the Double Deuce often indulge in crude and unruly behavior, Dalton is remarkable in his discipline. Before the bar’s small bouncer army, Dalton preaches that “All you have to do is follow three simple rules: One, never underestimate your opponent … expect the unexpected; two, take it outside, never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary; and three … be nice.” Dalton, explicitly, rejects violence for the sake of itself and uses his fighting prowess only when absolutely necessary. Dalton is the moral center of Road House, and his struggle to remain true to himself is the throughline of the movie.

More than that, it’s striking how Dalton is a hero without ego. Despite his reputation as a formidable asskicker, Dalton never shows off. As the Double Deuce’s cooler, he only intervenes when his charges need help. When love interest/town doctor “Doc” Clay (Kelly Lynch) remarks on Dalton’s surprising degree in philosophy from NYU (why are his college transcripts in his medical record?), Dalton humbly dismisses his studies as “Man’s search for faith. That sort of shit.” When Dr. Clay is puckishly hit on by Dalton’s mentor and friend Wade (Sam Elliott), Dalton doesn’t betray any jealousy and takes it in good humor.

I should be clear that Road House isn’t a feminist film in any kind of meaningful way. Aside from Doc Clay or spunky tomboy waitress Carrie Ann, women are mostly Barbie dolls to be rescued by Dalton or provide topless b-roll for the movie’s many bar scenes. But, interestingly, a kind of surprising male cheesecake element to the movie presents itself as well. Swayze spends much of his time on screen either shirtless or in a billowy karate gi top. As we watch Dalton do half-dressed tai chi on a farm, there’s a feeling of voyeurism that is undeniable. There’s a Magic Mike-ish beefcake eroticism to Dalton and the grizzled Wade, the latter of whom is happy to flash his pubes to the camera to show off a scar.

We admire Dalton because of his samurai-like code of personal ethics; he’s, in a sense, the ideal man. His integrity stands not just in defiance of the slobbish drunks he has to deal with, but especially the movie’s villain, small town crime lord Brad Wesley (Ben Gazzara).

Road House gives us two villainous counterparts to Dalton in the form of Wesley and his henchman Jimmy. While Jimmy mirrors Dalton’s intense physicality and provides him with a literal fight to the death at the end of the film’s second act, the egotistical Wesley could arguably be seen as Dalton without scruples or restraint. Wesley physically abuses both his henchmen and trophy girlfriend Denise. Dalton shies away from violence; Wesley is a gleeful sadist. Dalton uses his alpha-male powers for more noble purposes; Wesley uses them to maintain his status as Jasper’s two-bit ruler. Dalton’s influence encourages the bravery and hope of the townspeople while Wesley’s enables their baser instincts. Both men’s romantic relationships with Dr. Clay suggest that Wesley is the future self that Dalton fears he could one day become. A sort of Dalton of Future Past, if you will.

Dalton’s greatest conflict is within himself, in the form of an unquenchable blood lust. Road House cleverly sets this up fairly early on in the film, with a pair of background characters referring to an incident when Dalton ripped out a man’s throat. After Wesley sends Jimmy to blow up the home of Dalton’s friend/landlord Emmett, Dalton finally lets loose. Barely winning in a one on one fight with Jimmy, he is unable to stop himself from once again tearing out a man’s throat. A lesser movie would let this pass without remark, but Road House stages this scene so Dr. Clay, who is sworn to save lives, can only watch helplessly in horror as the man she loves commits murder.

You know that scene from Drive where Ryan Gosling gratuitously stomps a man’s head to goop in front of Carrie Mulligan? This is that, but somehow decades before Drive. Dalton, betraying his own code, finds himself estranged from Clay and at odds with himself.

After Wade is brutally murdered at Wesley’s behest, Dalton submerges deeper into the kill frenzy as he disposes of armed thug after armed thug at Wesley’s palatial estate. It’s only with all his inner strength that he is able to stop himself from performing his signature killing blow to wounded Wesley (who is, in accordance with the karmic laws of the Road House universe, blown away by shotgun-wielding townsfolk). Having redeemed himself, a weary Dalton is now free to resume a quiet relationship with Dr. Clay.

Road House, trash masterpiece that it is, is close to my heart for many reasons: great dialogue and characters, cool fights, a scene where a monster truck drives through a car dealership. But, ultimately, it’s the film’s meathead philosophical bent that makes it so immortally endearing.

Enjoy Stale Popcorn? Consider contributing to Deadshirt’s Patreon crowdfunding effort!