Film is an entertainment medium that, by its very nature, tends to reward the viewer in rewatch. Sometimes movies even reveal to us how we’ve grown or changed since we last saw them. Our own Max Robinson reassesses old favorites, seasonal classics and the occasional oddball lost under the couch in his monthly column, Stale Popcorn. This month, Max talks to Deadshirt staffer and E.T. super-fan Mike Duquette about Spielberg’s 1982 film.

Max: I hadn’t watched E.T. in at least ten years, so I was really excited to watch it with you the other night given that this is such an important movie for you, Mike. Can you tell me a little about your background with it?

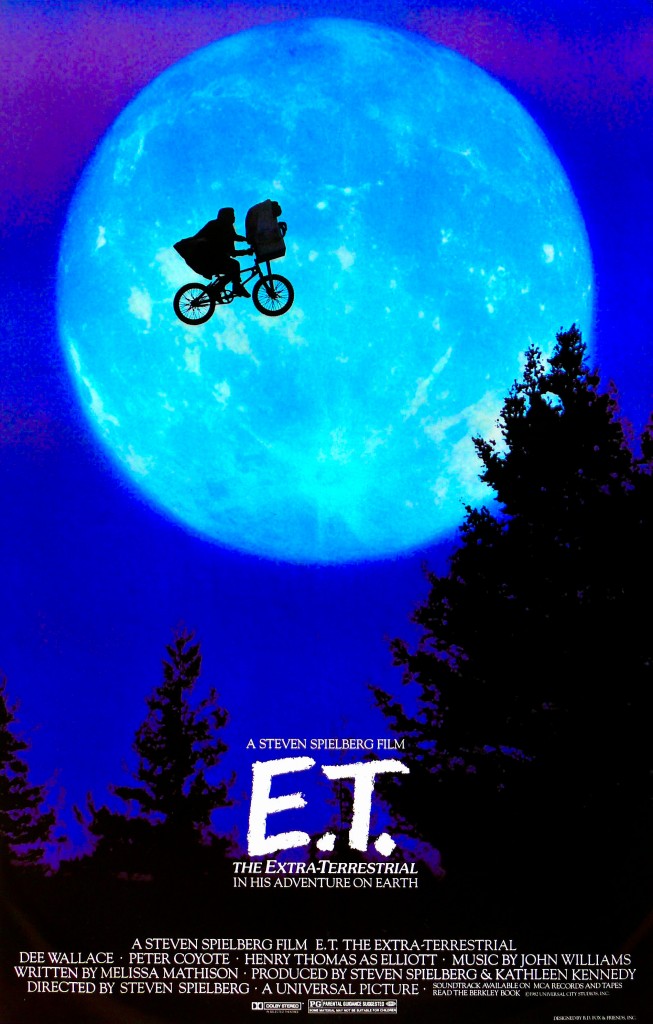

Mike: It’s almost weird to think of a time when E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial didn’t play a part in my life. I was very young—maybe three, at the earliest—and I found the VHS in a cabinet at my grandmother’s house. I was immediately taken by the box art–the iconic bicycle flying across the moon, the wrinkled “E.T.” letters in the lower third of the image—and decided it was something I should watch. Initially, I was very put off by the loud, disorienting first six minutes of the film, when our hero is marooned three million light years from his planet, but after a few tries, it became an obsession. I’d probably watch it daily, and as I got older, would check out E.T.-related books from the library, obsessing over both the story of the film and the story behind it.

It took years for the film’s gravity—which we’ll get to in a minute—to really sink in, but things like gorgeous special effects, pervasive childlike wonder, and the fucking brilliant John Williams score were with me from the start. Nearly everything I value in art and business (not only the entertainment I consume but the desire to professionally archive and contextualize it) comes from my years of reading about and into E.T.

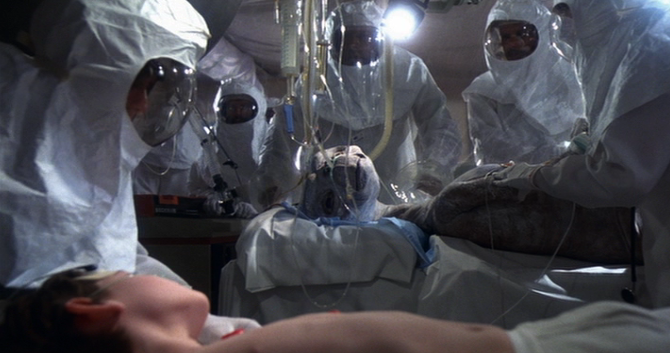

Max: First thought after it was over was “Man, this is like an UNRELENTING movie.” E.T. is the most emotionally exhausting Spielberg film that isn’t the one about, y’know, The Holocaust. A solid chunk of this movie centers around E.T. sickly and dying in a prone position. The third act of the movie really stays with you.

Mike: E.T. has retained this “feel-good” albatross over nearly 35 years, reflected not only in a host of imitation “lost creature” movies from Mac and Me to Free Willy, but also in how we view Spielberg as a Hollywood huckster placing raw emotional manipulation over craft.

E.T. bears a stunning amount of emotional heft. Consider our human hero, Elliott: the middle child in a frayed single parent household, too young to bond with his older brother and too old to relate to the younger sister. Henry Thomas’ portrayal of Elliott is often wounded and intense in a way that no photocopied children-in-peril drama has been able to touch.

Elliott’s (and the audience’s) meeting and bonding with E.T.—a bond that extends to a literal psychic connection—is put through the wringer. Can you imagine, say, Beethoven, the movie where a St. Bernard constantly owns Charles Grodin, featuring a literal death scare for the dog? And yet E.T. (temporarily) dies with E.R. intensity! There’s real doctor crosstalk and Drew Barrymore’s little sister jumping in fright as defibrillator paddles shock our alien hero. And it works, because we’ve been given so much time to appreciate E.T. as a character.

Max: The movie feels almost abstract in terms of how it balances emotion with story logic? The shitty suburban family dynamics are incredibly realistic, all the stuff with Gertie and Elliott and his brother (Spielberg knows how kids talk better than just about any other director I can think of) but plot-wise everything feels like surreal? Especially when you get into the government goon stuff and you have like LITERAL ASTRONAUTS walking through Elliott’s house. The scene with Elliott liberating the frogs is exactly what I’m talking about, the choreography of it.

Mike: It’s almost like a fairytale. I once read someone assess E.T. as an inverted, reversed The Wizard of Oz, where a visitor from a mysterious other world lands in drab suburbia full of brains, heart, and courage, and risks it all to get back home that literally ends on E.T.’s spaceship flying over the rainbow.

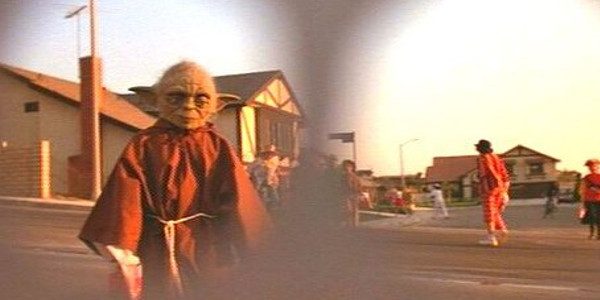

But it’s also grounded in this intense, Reagan-era reality. Max, you brilliantly pointed out just how pervasive Star Wars is to these characters, with Michael teasing Elliott in a Yoda voice and Elliott showing off his action figures to E.T. (to say nothing of the cute metatextual moment where E.T. encounters a Yoda on Halloween to the tune of Williams’ theme from The Empire Strikes Back).

Max: It’s fascinating to watch this movie on the eve of all this excitement for The Force Awakens because we forget that, oh yeah, Star Wars was this fucking impossible cultural phenomenon. Like, on paper, all the Star Wars refs sound like they wouldn’t work, but it’s a choice that really situates E.T. in a hyper-specific time and place (the American suburbs in the fall of the early ’80s). Also kind of fitting/funny that there’s all this Star Wars stuff in E.T. when E.T. is pretty plainly a huge influence on J.J. Abrams’s entire body of work.

Mike: Thinking of Abrams and his push for a more practical effects-laden Star Wars universe, E.T. may be one of the high watermarks for that sort of filmmaking. The craftsmanship that went into E.T. as a special effect who is also a character is revelatory. He’s almost disturbingly real, thanks to Carlo Rambaldi’s delicate animatronic work as well as the lesser-credited Caprice Rothe, a mime who supplied E.T.’s tentative hand movements. E.T. is so perfect that every attempt to render him more lifelike with computer animation, including the ill-conceived enhancements of a 20th anniversary re-release in 2002, looks amateurish.

Max: Spielberg seems to understand that in order for this entire movie to work, the audience can’t ever be thinking of E.T. as a special effect. I was just astounded by how well this completely practical effect holds up, and how you pretty much immediately buy into E.T. as a character. Jurassic Park operates under the same principle; there’s gotta be some sleight of hand there where we totally buy in, or it’s just The Avengers fighting a million CGI Ultrons or whatever.

Mike: And the go-to folks at Industrial Light & Magic shouldn’t be counted out, either, for their work on E.T.’s beautiful spaceship and the profoundly moving bicycle flight scenes.

Max: I’d totally forgotten that there are two distinct “flying bike” scenes in E.T. The slight dip Elliott’s bike takes just before it goes soaring through the woods in the first scene is such an amazing little detail that I never appreciated until now.

Mike: It’s a movie that gets to have it both ways, which is really unlike anything in Spielberg’s filmography, or in Hollywood history, for that matter. It’s at once this raw, emotional, character study and this megaton Hollywood blockbuster (the world’s highest grossing movie for over a decade, after a number of hot potatoes in the ’70s, from The Godfather to Jaws to Star Wars). That duality is cunningly on display throughout the film, making several characters sharply analogous. It’s pretty obvious with E.T. and Elliott, but less so with Elliott and the mysterious “Keys,” played by Peter Coyote and seen mostly as a silhouetted, faceless government agent until the last act.

Max: Peter Coyote’s character is really interesting to me because I didn’t remember him having this big a role. And I definitely didn’t remember his weird mini-monologue to Elliott where he talks about E.T.’s arrival being a miracle. I like that the movie doesn’t ask us to take him at anything more than face value; there’s no scene where he rolls up in a Jeep to bust out E.T. or anything. He’s a strange, sad guy who we aren’t really sure what to make of up until the end. And that’s good, because I feel like it’s crucial that the kids are the ones who save the day. You get the impression that the adults of the film are too fundamentally broken to really “get” E.T.

Mike: Spielberg gives the kids such a wide berth (he shot the film in rough sequence to coax real reactions from them over time), and that’s one of E.T.’s greatest strengths. Even as weird, broken-down shell adults, there’s a lot of weighty, ultimately beautiful feelings to gain from this little big movie.

Max: Dee Wallace does A LOT with what could’ve very easily been a thankless part as Elliott’s mom. The way she can’t quite stop herself from laughing when Elliott calls his brother “penisbreath,” her delayed reaction to Elliott showing up after running off on Halloween.

Mike: And those laughs—and there are many—are tempered with moments that just get you “in the feels,” as Internet morons like to say. Moments that you, along with Dylan and Julian, watched me personally, viscerally react to.

Max: Yeah! When we got to the scene where Gertie’s carried out of the room by her mom, you started openly sobbing. And I hope this isn’t embarrassing but that like…that was so cool, to me! Watching you have this INTENSE emotional reaction to that scene, which you know by heart, that speaks to the lasting power of E.T. Watching three other people get drawn into the film like that, it was a powerful experience.

Mike: Like I told Julian, I always know it’s coming, but I’m never sure how hard it’ll hit. At 28, with a boatload of new, deeply personal experiences to my name since the last time I watched (by now it’s more of an annual occurrence), that moment hit me harder than it’s ever hit. And in a weird way, that’s why I keep watching: everything E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial has meant to me through all this time is, incredibly, worth something.

Check out more Stale Popcorn by Max Robinson.