It’s getting colder out there. It’s getting darker. In honor of “Noirvember,” Deadshirt’s decided to turn the spotlight on our favorite modern noir films of the last couple decades. Eyes forward, put the money in the bag and don’t get cute. This is Neo-Noirvember.

If you’re talking about neo-noir, Blade Runner is required viewing; Blade Runner is neo-noir. Ridley Scott’s interpretation of Philip K. Dick’s bleak portrait of futuristic Los Angeles bombed when it was released in 1982, but has since garnered well-deserved critical acclaim. Blade Runner is my very favorite movie —particularly the Final Cut, the last of seven (!) different versions of the film.

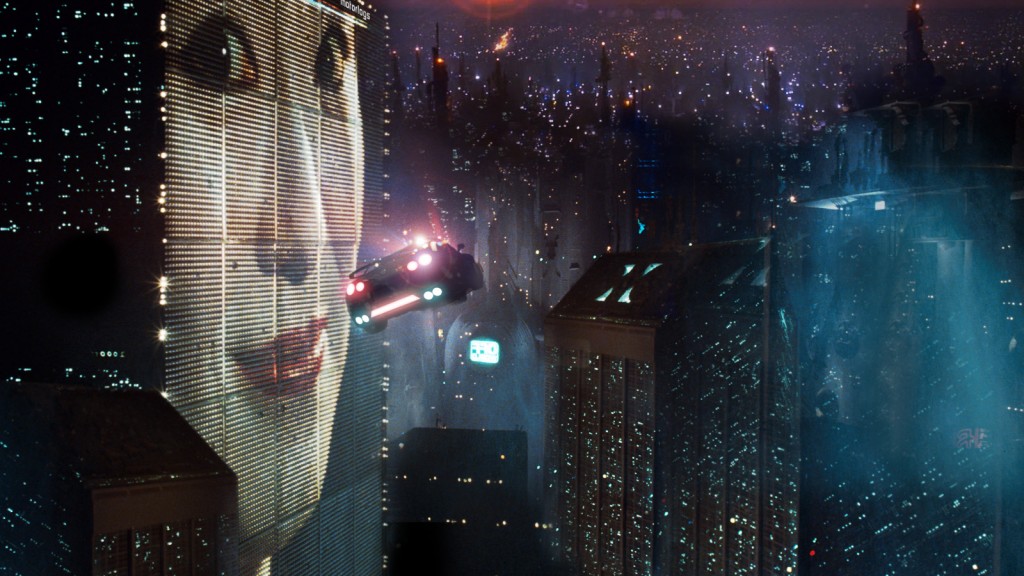

Blade Runner’s Los Angeles is a world of sputtering neon and endless rain, where desperate people hustle through the trash-strewn streets, and grimy hovercars zip overhead. Earth, as it seems, is used up, and those with money are leaving the planet for the burgeoning colonies on Mars.

For those on Earth, life is grimy and lonely, and oftentimes unpleasant. When a group of the monolithic Tyrell Corporation’s lifelike android Replicants develop self-awareness and escape to L.A., burnt-out bounty hunter Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is forced out of retirement to hunt them down and kill–or “retire”–them before the public finds out.

Deckard has been at his work too long, and it shows. He’s a cynical alcoholic, and despite his reputation as an effective “blade runner,” he’s in over his head. The replicants, led by the charismatic and violent Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) are both intelligent and superhumanly powerful, and they seek to gain an audience with their creator, Eldon Tyrell, in hopes of getting their very brief four-year lifespans extended.

Deckard does as much detective work as he does “retiring,” plunging in and out of the endless rain as he tracks down the fugitive androids, some of whom have taken up odd jobs to maintain their cover. It is with the pragmatism and determination of a man without a choice that he goes about his work, at each turn finding himself far physically outmatched. Deckard is not an action hero. His aim is unsteady, and he often finds himself on the receiving end of vicious android beatings.

The only warm spot in Deckard’s life is Rachael, an experimental Tyrell Corporation Replicant that’s unaware that she isn’t human until Deckard’s Voight-Kampff test shatters her reality. As Deckard continues to hunt down and kill the other Replicants, he begins to fall in love with Rachael and question the morality of his work. What is it that defines humanity? Are the androids more than machines?

Certain cuts of Blade Runner are saddled with a poorly written voiceover narration from Harrison Ford, which is rightfully excised from the superior Director’s Cut and Final Cut. The film is much better off without it, leaving much of the characterization to come through the subtleties in portrayal and dialogue. In a sense, not being allowed into the head of the protagonist leaves you isolated, and more in tune with the vibe of the film. Deckard, fresh off killing a Replicant in the street and nursing a busted lip, offers a sarcastic smile when his boss calls him “a goddamned one-man slaughterhouse.” You’re left to wonder if Deckard is repulsed by the words, or if he’s repulsed by what he sees in himself. Blade Runner exists best as a world of unspoken thoughts and internalized anxiety. It’s a world where there is no one to confide in, and no escape from guilt but at the bottom of a glass.

The feeling of time slipping away hangs over the whole movie. Roy is very near the end of his four-year lifespan, and the imagery of him driving a nail through his hand to force feeling back into his system is an unsettling and effective way to show it. The plight of the fleeting Replicant lifespan is perfectly illustrated midway through the film when Deckard is beaten into near-unconsciousness by android heavy Leon, who simply shouts “Wake up! Time to die.”

Blade Runner is a tapestry of loneliness, and there seems to be little that can be done to ease the pain of our cast. Even the love between Deckard and Rachael often feels cold and alien, symptomatic of two people who have no clue how to handle their emotions. At times, it seems as if they only love each other simply because it is a comfort in a world of isolation and violence. Almost every interaction between them drips with fear and distance: a self-loathing drunk and a doomed, desperate runaway searching for warmth where there is little to be found.

The rampant symbolism of Blade Runner pulls in a lot of directions, and one of the biggest questions left lingering at the end is also one of the most impactful. It is implied throughout that Deckard himself may be a Replicant, wound up by the LAPD to hunt down rogue androids. We are never given a straight answer, and as Deckard and Rachael leave his apartment toward an uncertain future, you wonder if it even matters.

Check back each week for more Neo-Noirvember essays from Deadshirt.