In Black Snow, the Deadshirt crew takes a look at some darker entries in the yuletide cinematic canon.

Like much of what we’re covering this month in Black Snow, Gremlins is a movie at cross purposes, skewering traditional and conventional expectations of holiday fare while still providing a narrative that embraces the emotional core of the Christmas season. As a film stuffed with a cartoon cast that offers up a paean to chaos, it succeeds beautifully.

We open with Hoyt Axton’s Rand Peltzer, a struggling inventor and salesman who’s attempting to sell a combination toothbrush, shaving mirror, floss, toothpaste dispenser, toothpick, nail clipper, travel… thing to a farcically stereotypical Chinese businessman (Keye Luke) in a tiny shop festooned with dragons and other Chinatown memorabilia. Taking interest in a tiny furry creature known as a “mogwai” that the shop owner refuses to sell him, he manages to cut a deal with the owner’s grandson (John Louie) in exchange for the creature, seeing it as the perfect gift for his son. After this brief overture, the first act begins in earnest, beginning to introduce us to the cartoon cast of oddballs that populate Kingston Falls and will soon fall victim to our titular creatures’ particular brand of weaponized shtick.

The entire first act of Gremlins is mostly table setting, though don’t take that as a criticism. It’s necessary groundwork that establishes the slapstick sensibility of the film, considering that so much of the back half of the film is dedicated purely to set pieces and hijinks. Gremlins takes place in a world a few steps away from our own, one inhabited by the Perennial Perfect Special Little Man Gizmo, one where Corey Feldman delivers Christmas trees dressed as an actual Christmas tree, one where we’re supposed to believe that an inventor is struggling to make ends meet despite developing an orange peeler and juicer that produces several gallons of juice from a single orange and a coffee maker that dispenses the black oil from the X-Files, one where Phoebe Cates is still Phoebe Cates because some things are thankfully multiversal constants.

The tone built in the first act of Gremlins is essential to its success. Things like the comical villainy of Polly Holliday’s Mrs. Deagle (a rich, miserly woman who seems to be the landlord to everyone in town) or the drunken earnestness of Dick Miller’s Mr. Futterman, who insists that foreign gremlins have bedeviled his snow plow (fun fact: Some historians attribute the use of gremlins as scapegoats with helping R.A.F. pilots avoid plummeting morale during WW2) allow us to build a healthy distance between the world of the film and our own, making the encroaching mayhem and violence to be darkly comic instead of gritty and dreary.

During this establishing act, we meet Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan). A young man who works as a bank teller to help his family put food on the table, he’s the recipient of Gizmo and is the audience’s surrogate through the film. It’s through him that we meet Mrs. Deagle, who seems to have a predilection for dog murder, Mr. Futterman, who insists on buying American, and Kate Beringer (Phoebe Cates), who has an issue with the holidays because it brings back memories of her father’s death. Which seems reasonable. There’s no joke there, that seems like a perfectly sensible reason to not get psyched over Christmas.

Billy is friends with both Pete Fountaine (young, befreckled Corey Feldman), who spills a conveniently placed jar of water onto Gizmo, causing him to multiply into a whole cavalcade of fuzzy friends, one of whom Billy brings to his science teacher (Glynn Turman) to examine (probably where The Faculty got the idea). This puts the pieces in play for the story, as the rest of the mogwai, none of whom seem to have the friendly and wholesome disposition as ya boy Gizmo, trick Billy into feeding them after midnight by chewing through the wire of the analog clock in his room. Apparently their entire plan banked on him also not looking at any other clock in the house. The precocious mogwai enter their pupal stage and are eventually reborn as gremlins, making Turman’s teacher their first victim.

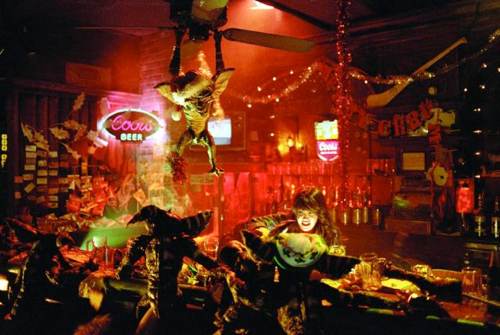

With the appearance of the titular monsters, Gremlins really hits its stride, and it’s the irreverent reptilian beasts themselves that make the film so memorable. Gremlins are the personification of “doing it for the bit,” they kill and are killed almost exclusively through vicious shenanigans. Columbus’s script is sensible enough to lean into the curve at this point in the story, taking a break from the close focus on Billy to allow us to explore a series of vignettes as the gremlins (population bolstered by their leader Stripe’s visit to a local YMCA) overrun Kingston Falls. What Gremlins understands is that The Bits are the heart of this movie. From the gremlin carolers to a gremlin-manned renegade snowplow, to the amazing set piece in a dive bar that appears to be staffed solely by Phoebe Cates, each captures the kind of whiplash-inducing Looney-Tunes-meets-creature-feature energy that has made the movie such an unforgettable piece of pop culture.

After this extended exhalation of tension, Billy and Kate resolve their gremlin problems by blowing up a movie theater and chasing Stripe into a water fountain, where Gizmo delivers the final blow thanks to some fortuitous skylight placement. The Chinese shopkeeper from the opening returns, giving us a lecture on how humanity is not yet responsible enough to care for the mogwai, but that Billy may yet earn the right to see Gizmo again in the future. This broad declaration on human nature is, thankfully, as close as Gremlins ever really gets to a moral, choosing instead to embrace the hectic and occasionally lethal fun that the starring creatures create.

What allows Gremlins to work is that it is bursting with an effusive enthusiasm not seen in many other films. Everything from the brilliant score, a perfectly balanced blend of bounciness and unease, to the brisk and efficient direction propel the film forward. It’s packed with small, irreverent touches that never call too much attention to themselves, but reward an attentive viewer. Whether it’s Steven Spielberg wheeling by on a recumbent bicycle while a time machine disappears in the background, or the camera panning past a gremlin cheating at cards by hiding a pair of aces behind his ears, Gremlins is electric with a kind of energy that makes you feel as though it must have been as much of a blast to film as it is to watch. It’s a dark slapstick ballet that is insistent on allowing its audience to be in on the joke with it. The holiday season always brings its fair share of madness, uncertainty, and chaos. What Gremlins suggests is that sometimes the best option available is to lean into the skid and try to have a few laughs along the way.