When asked about the current state of his relationship with his one time BFF, megastar comic scribe Mark Millar, during a series of interviews promoting his book Supergods, Grant Morrison said, “I wish him well, but there’s no good feeling between myself and Mark for many reasons, most of which are he destroyed my faith in human fucking nature.”

We have all had friends who turned their phones off when you had to move, or bedded someone you had expressed an interest in, or still have not returned your entire collection of Sandman trades. It’s not often that someone you once considered your closest compatriot turns out to stand for the opposite of everything you believe in, unless you are a character in Smallvillve, to which I say, “I am sorry.” Grant Morrison, legendary funnybook writer/former druggie sex shaman/conduit to the 5th dimension, largely tells stories that are full of hope and wonder and a sort of postmodern take on Silver Age super sci-fi. His works are often sprawling and complex, full of a vibrant sense of life and told from a distinctly humanist, aspirational perspective. Mark Millar once wrote a comic where a villain forced his opponent’s son and daughter to copulate, then rigged the daughter’s womb with explosives so she couldn’t abort the child they conceived.

You know, in retrospect, maybe Morrison should have seen this coming.

At one point in time, Morrison and Millar were were friends and collaborators. Together the two were responsible for such 90s gems as Aztek, The Ultimate Man and Skrull Kill Krew, as well as an underrated run on The Flash. Millar was something of a protege for Morrison, and it seemed Millar would follow in his mentor’s footsteps. Millar’s big break came when he took over Warren Ellis’ seminal series The Authority, which led to his work on Marvel’s Ultimates line, which led to seemingly every creator-owned project he churned out becoming a feature film, which led to the Mark Millar we know today: the hyperbolic showman who never seems to be telling the truth, and displays utter obliviousness when presented with the inalienable truth that his work is bankrupt of decency and feels crafted by a horny, teenage sociopath.

The source of their falling out is said to be related to Morrison ghostwriting an issue of Millar’s final arc on The Authority. At the time, Millar was incredibly ill, which also caused delays on his other titles, and to pitch in for his friend, Morrison banged out an issue, like it was no big deal. There are multiple sides to the thing, but Morrison’s unsolicited acknowledgment of this deed in an interview is thought to have incensed Millar, who must have thought it was a quiet gesture between friends, and not fodder for comic gossip. Throw in Millar’s mounting mainstream popularity and ability to get literally any project a hit, coinciding with Morrison’s frustrations in finding a footing in Hollywood, and whatever other backstage backstabbing occurred, and you have a feud.

Later, in that same Supergods promotional tour, Rolling Stone asked Morrison if there was any chance of him running into Millar in Glasgow, where they both still live. “There’s a very good chance of running into him, and I hope I’m going 100 miles an hour when it happens.”

Yeah.

Anytime he’s questioned about it, Millar shrugs it off, ever gladhanding and smiling. He claims to still love Morrison’s comics and harbors no ill will. There’s no snarky tone here, either. It’s possible that waking up one day and seeing a royalty check for a movie like Wanted may have left him completely immune to any dosage of weapons-grade haterade. He claims the duo hasn’t spoken in over a decade.

The silence was broken with Morrison and Darick Robertson’s Image series, Happy. A one way conversation still counts as talking.

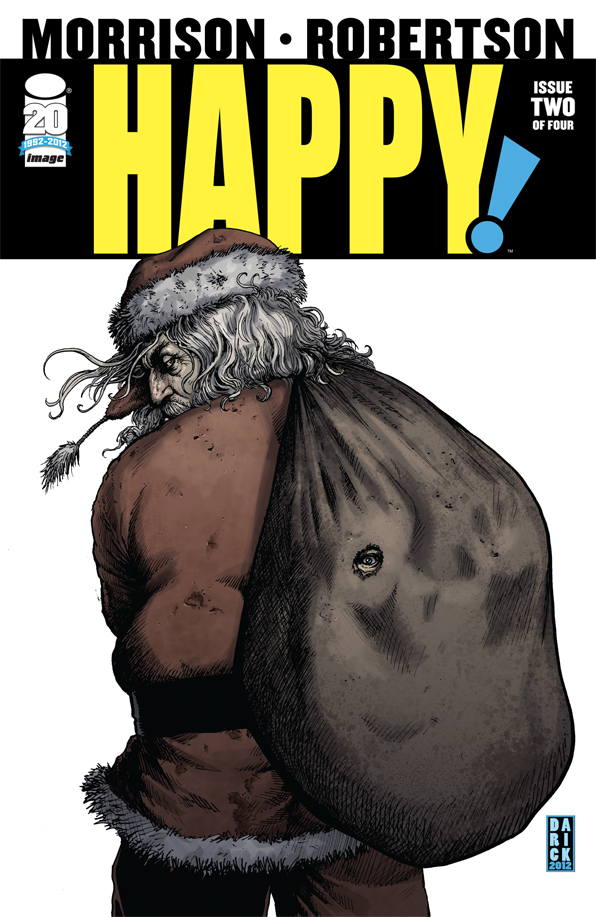

Jesus, lad, tear the hole open and make a run for it! Billy Bob Thornton just hasn’t been the same since that Bad News Bears remake.

There are many things to like about Happy.

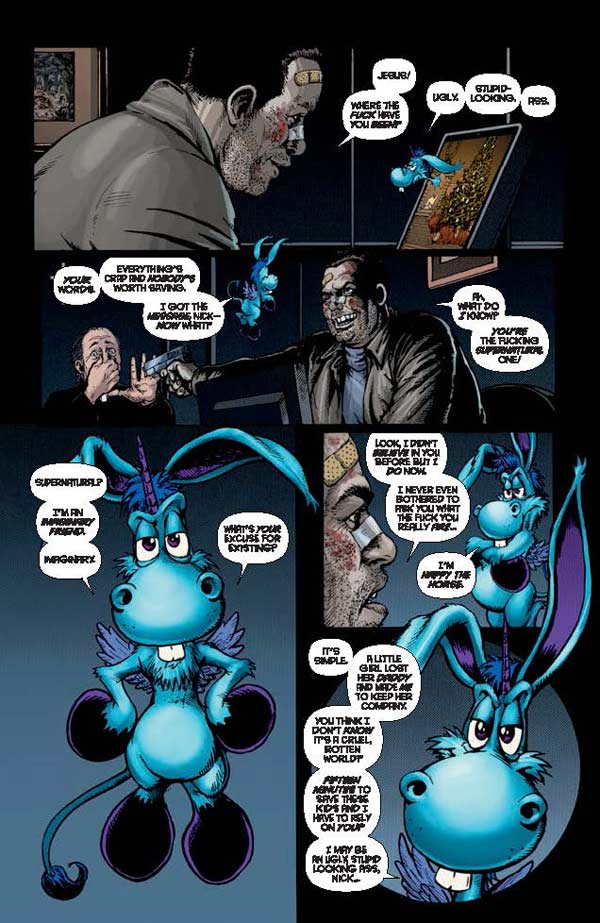

Robertson’s dark and gritty pencils are perfectly suited to the tale of Nick Sax, an ex-cop turned hired gun who begins to see visions of a smiling, blue donkey/pegasus (named “Happy”) who wants him to save a little girl being held captive. The book is a note perfect riff on the kind of ultraviolent, F-bomb ridden “Mature Readers” fare Garth Ennis is known for. Warren Ellis makes books in this same vein, as well, but the pointed critique of cynicism and vacant morality has far more in common with Millar’s later Icon work. Just the image of a Santa suit pedophile alone is enough to call to mind the image of Millar in front of his keyboard, chuckling and shaking like Beavis in full on Super Saiyan Cornholio mode, wracking his brain to think of new and untold portrayals of needless debauchery.

Morrison says that the titular Happy is based on an obscure psychedlia song he remembered from his youth, and that he was fascinated by juxtaposing a constant source of pure positivity against the dirt encrusted, semen stained cityscape that represents the sum total of negativity in our society. He framed the story as his ultimate “fuck you” to Simon Cowell dressing down poor vocalists on television, and to the comments section of every blog in the world.

A crime story that follows the form and function of a typical noir, but with a kidnapped child’s imaginary friend, who may or may not be a drug fueled delusion, teaming up with the gruff anti-hero to save the day at Christmas time? It’s like if Shane Black made a movie with Sid and Marty Krofft.

The prevalent strong language is so inescapable as to border on absurd. Characters curse so much that by the second issue those words may as well be commas. There’s a dark humor at play that might be cheesy in a book less dedicated to this specific tone. Sax throwing a man dressed as Old Saint Nick out of a window while quipping “There’s no such thing as Santa Claus” only for a cop to muse “Christmas came early” when his carcass hits the top of a squad car is so bad it’s brilliant. It’s as if Morrison took a dive into this cesspool of gritty comic tropes and found something to smile about, no matter how bad the stink.

Morrison isn’t above speaking directly to people through his work. The Invisible ends with talking directly to the reader, eschewing any semblance of whatever remained of the fourth wall. At the end of his epic Batman Incorporated run, a sword fighting Talia tells Bruce: “Look, I know you like the rules to be cartoonish and the stakes to be clear.” That’s Morrison talking to the audience and the industry that led to the Nu52 interrupting much of what he wanted to accomplish with the character. Happy is Grant Morrison saying to Mark Millar what he hasn’t been able to properly articulate for ten years.

In the penultimate issue of Happy, during a flashback, Nick says of the world: “It’s gift wrap on a fucking skull.” To which his mistress/police partner muses: “Sometimes the shine on the gift wrap’s about the best we can hope for.” In the context of the story, it comes off as the sort of tragic, noir one liner narratives like this are built on, but coming from Grant Morrison, that gift wrap shine isn’t some throw-away silver lining. For Happy, it’s all you need to get the engine started. As Kanye West might say, it’s the espresso. Having discovered Sax’s past, the lovable Fauxnicorn tries to convince Sax of the magic of Christmas and the beauty of humanity to motivate him on his quest to save the little girl.

They’re on a train and Happy rushes out of the bathroom to show Sax the car full of what he expects to be lovely, happy citizens excited to be traveling to be with their loved ones. Instead, he finds a bunch of jaded, selfish, jackasses complaining into the smartphones and griping about their trivial problems. This display is what finally makes a dent in Happy’s resolve. The only thing he can say to this is “Meh.” This leads to the big plot bombshell of the story, but at this moment, his character is spent. He’s done all he can to convince Sax that the world isn’t as awful as it seems.

That is Grant Morrison. He snorted up the entire history of Batman and shot it back out as a cultural lightning bolt. He’s devoted his recent work to showing audiences that there’s nothing wrong with a little Truth, Justice & The American Way, and yet Millar’s shallow gunfuckfests keep getting greenlit by Hollywood. It’s as if he’s tired of fighting back. In the story, Sax finds out a vital piece of information about the captive girl he needs to save, and begins to believe on his own, but here in the real world, Millar hasn’t picked up the other half of this conversation. Morrison is still on the other line waiting for his old friend to see the light and save the day.

Mark? Phone’s for you.

Seriously, this is a great take on Happy and a perfect summation of why I’m still (and likely forever shall be) a Morrison fan while Millar’s name on a book has ceased to hold anything for me.

“…shaking like Beavis in full on Super Sayian Cornholio mode…” That is such a hilarious and amazing phrase. I know we’re a few years on, but this take on Happy is well thought out. I hope you’re out there writing more amazing stuff, Dominic.