Christopher Nolan is a director whose work betrays an understanding and dedication to showmanship. He records few deleted scenes and even fewer commentaries on his films. He’s a filmmaker who understands the power that comes from limiting what your audience sees. As Christian Bale’s Alfred Borden notes in Nolan’s The Prestige, a movie almost totally concerned with the art of presentation:

The secret impresses no one. The trick you use it for is everything.

It’s no surprise then that one of the most developed and nuanced elements of Christopher Nolan’s Batman films is the creation and implementation of personas. The line between Batman and Bruce Wayne is an idea that’s been explored to some extent in comics, but is surprisingly glossed over in most of his movie and television incarnations. Looking at each film in the series, there’s an interesting, overarching narrative created by the evolution of the Batman symbol, Bruce’s own legacy and the similar personas he is pitted against.

The first thing we see in Batman Begins is a giant writhing mass of bats, then a crude bat emblem forms out of them and into the “official” logo. Before we even get into the action, we are presented with a symbol. Throughout the movie, Nolan walks us through the process of Bruce creating the Batman identity from its most abstract roots to the final, polished identity. We even watch Bruce literally build the Batman; spray painting his suit, creating shell corporations to order the pieces needed for his armor, sharpening bat-a-rangs. We watch him falter and fail.

As the film begins, Bruce falls into a well on the grounds of Wayne Manor and he’s frightened by a nest of bats. Following the death of his parents and subsequent growth into a young man, Bruce has shed his Bruce Wayne identity while he travels through China. He’s bearded, unwashed and imprisoned, living without his wealth. When Bruce meets Ra’s Al Ghul, he spells out what will become the underlying concept that binds all three films; A man is mortal, a symbol can become immortal. As Bruce’s mentor, Ra’s teaches him what will become the fundamentals of his war on crime.

Theatricality and deception are powerful agents against the uninitiated.

Through Ra’s teachings, Bruce learns not only how to fight better, but how to make himself appear almost supernatural; coming and going unseen, using distraction and, most importantly, the art of the false identity.

Unlike the literal immortality of his comics counterpart, Ra’s’ longevity is a philosophical one; the implication being that this Ra’s Al Ghul is merely the latest holder of a title. Further, Ra’s is seemingly unkillable because he hides behind human doubles. Liam Neeson’s Ra’s is introduced to us as a man named Henri Ducard, a mere servant of Ken Watanabe’s white bearded Ra’s Al Ghul. The false Ra’s preys on our expectations; of course the leader of a far east warrior cult is a mysterious asian man. When one false Ra’s dies, he simply replaces them with another and on and on Ra’s lives.

As a symbol I can be incorruptible, I can be everlasting.

When Bruce turns against Ra’s’ League of Shadows, he uses their lessons and his own ingrained experiences to craft what will become Batman. Bruce takes his childhood trauma of the bat-filled well, the acrobatic imagery of demons in a production of Die Fledermaus and the kindness he received from a young Jim Gordon on the night of his parents’ murder to inform the methodology and moral center of his new identity in the war on crime. Using what he’s learned, Bruce appears more than human through the creation of fear and misdirection. He puts on a low growl when he interrogates men, he appears upside down without warning to frightened criminals.

The counter-narrative here is Bruce’s open disdain for his own identity; Bruce Wayne, heir to Wayne Enterprises. As a young man, Bruce refuses to sleep in the master bedroom of Wayne Manor, wishing he could destroy the property brick by brick (ironically, he ends up rebuilding it at the end of the film). Bruce argues with Alfred over whether the family name and estate matters; Alfred refuses to let Bruce turn his back on his home out of respect for the memory of Thomas and Martha Wayne.

It’s not just your name, sir, it’s your father’s name and it’s all that’s left of him. Don’t destroy it.

After becoming Batman, Bruce finds use for his public persona as an outrageous celebrity; a distraction, a cover for his nightly activities and a means of supporting his war on crime (both directly through Wayne Enterprises’ resources and later as a means of corporate espionage). Bruce even goes as far as sacrificing his public standing and family name with a fake drunken tirade that sends guests at his birthday party away from the wrath of the League of Shadows.

As Batman, Bruce first fights Dr. Jonathan Crane in his Scarecrow persona. Crane is something of a bastard disciple of Ra’s, he uses his understanding of psychology and psychopharmacology to terrorize others, but for nothing deeper than the domination of those he sees as inferior.

When Bruce, as Batman, and Ra’s Al Ghul face each other at the end of the film, their similar methodologies are tested against one another. The League of Shadows uses deception and espionage to attempt to destroy Gotham, Bruce uses these same tactics in order fix Gotham’s societal ills and combat crime. By the end of Batman Begins, Bruce has defeated Ra’s (using his own lessons) and left him to die. In a sense, the myth of Batman has destroyed and replaced that of Ra’s Al Ghul. At least for a time.

Nolan’s 2008 follow up, The Dark Knight, opens not on Batman but on The Joker. Or rather, the idea of The Joker. We hear his henchman talk about him in the kind of awed whispers we heard ordinary citizens talk about Batman in the prior film.

I hear he wears make up.

Make up?

Yeah, to scare people. You know, war paint.

When we first see The Joker in the film, it’s from behind holding an empty clown mask. The visual of the empty mask defines Ledger’s take on The Joker pretty succinctly; The Joker is pure alter ego, with seemingly no human face underneath. We have no idea who The Joker is under the makeup and it doesn’t really matter. While Bruce’s Batman persona is supposed to strike fear in the hearts of criminals and serve as an aspirational figure to Gotham City, The Joker manipulates people into following their craven, base instincts; his henchman have no problem blowing each other away at the instruction of a man they barely know.

When the focus turns to Batman, we see that he’s winning the war on crime; street-level criminals are running scared, the mob is in disarray and his relationship with local authorities is solid. The unintended side effect of this is that he’s inspired copycat vigilantes. As we watch Batman masterfully defuse a drug deal gone awry, we see that Bruce has perfected his persona. He’s mastered the entrance, he’s a rock star. However, as crime boss Salvatore Maroni points out, Batman faces a very big problem with his image. To wit, everyone knows Batman won’t kill. Criminals may be afraid of him, but his avenging demon from hell image is softened because he won’t break his “one rule”.

The Joker’s appearances in the film are almost supernatural, he appears as if out of thin air at times. He appears to us, the audience, the way Batman appears to characters within the film. The Joker’s lack of a definitive origin has been a core element of the character since the 1980’s and we see it here in the wildly different explanations The Joker gives for his mouth scars. This is important because it highlights how Nolan’s Joker is a man utterly unconcerned with the truth, only the appearance of truth.

Ledger’s Joker uses the tactics of a terrorist insurgency, releasing videos of torture victims, implementing cell phone bombs and targeting high-ranking public officials like the mayor. Like Ra’s or Scarecrow, he uses fear but he’s far more effective than they ever were at creating panic. Joker and Ra’s’ ultimate endgame is for Gotham to tear itself apart in terror but Joker opts for dramatic imagery such as a solitary firetruck going up in flames or an exploding hospital over more literal fear gas Bond villain tactics.

When Batman interrogates a captive Joker, he implies that he knows Bruce is Batman because of his obvious affection for Assistant District Attorney Rachel Dawes, but rather than threaten him with this knowledge, The Joker treats it as something of a joke between friends; he doesn’t care who Batman is underneath the mask. The Joker even threatens the life of Coleman Reese, an accountant who stumbles onto Wayne’s alter-ego, to preserve “the mask”.

In The Joker, Batman faces a man who is even more formidable at deception and theatricality than he is. Batman initially underestimates The Joker, writing him off as the kind of common criminal he’s so effectively conquered in the past and not a man, like himself, motivated by ideals (in this case, death and mayhem for its own sake. Crime as social statement rather than a moneymaking concern). Alfred understands this and attempts to explain it to Bruce, but he’s too proud to listen until it’s too late.

Gotham needs a hero with a face.

Harvey Dent’s role in The Dark Knight is an interesting one, especially compared to his more traditional super-villain role in the comics. In Dent, Bruce sees the kind of public inspirational figure he can never be. Dent’s affectation, putting decisions up to the flip of a silver dollar, is a theatrical flair of his own; as it’s a double sided coin, Dent isn’t actually putting anything up to chance.

When he is disfigured and driven insane by The Joker, the other side of the coin becomes burnt. As Two-Face, Harvey cares only about revenge on those he thinks have wronged him. The function remains the same, though; Harvey has no problem finding loopholes when his coin refuses to come up on the “bad” side. The corruption and eventual death of Harvey Dent threatens to destroy the footholds in the eradication of crime that Gordon and Batman have fought so hard for.

In the end, Batman takes the blame for Harvey’s crimes and the fundamental nature of his image is changed. To protect the untarnished image of Harvey Dent, heroic public crusader, Bruce allows Batman to be seen as a villain. And in a sense, he has started to become one; he abuses the sonar technology developed by Lucius Fox in an ethically dubious attempt to find The Joker.

This fight with The Joker has stretched his ideals as Batman to a breaking point. Ultimately, Bruce and Gordon agree to uphold a lie for the supposed greater good of Gotham.

This brings us to The Dark Knight Rises, the third and final installment of Nolan’s Batman trilogy, which opens on Harvey Dent’s funeral, presumably shortly after the events of TDK. We learn that Gordon and Batman’s compromise worked, Gotham is a city free from major crime thanks to a piece of legislation known as the Dent Act. It’s a hollow victory; Batman is gone, Bruce is a Howard Hughesian recluse and both Gordon’s career and personal life are in shambles. Harvey Dent’s pre-disfigured face had taken on symbolic power of it’s own, a propaganda image not unlike the images of the World Trade Center on 9/11. In this disruption of the balance of power, Gotham’s police force have grown ineffective and the city is ripe for attack.

No one cared who I was before I put on the mask.

The major action moves to an undisclosed location, where a CIA agent interrogates several captives about “Bane”. Like The Joker, Bane is pure alter-ego. His voice and his gestures are highly theatrical in the manner of an evangelical preacher. Bane is power, personified; not only does he have incredible physical strength, he’s a charismatic leader of men who will die at his command. When evil industrialist John Daggett confronts him, Bane stops him cold by simply placing his hand on his neck. Daggett believes that power comes from wealth, Bane shows him this isn’t so when effortlessly he kills him and takes that wealth from him.

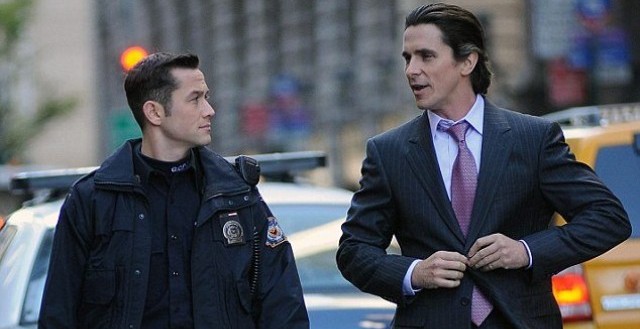

When Bruce Wayne encounters Officer John Blake, who grew up orphaned and impoverished, we see the aspirational power of his public face that he has tried to deny for so long; Blake explains how he and his friends idolized “Bruce Wayne, Billionaire Orphan”, even making up stories about him. Through his conversation with fellow well do’er Miranda Tate, we learn that Bruce has attempted to do good in the world in his own name but failed, spending much of his fortune developing and ultimately shuttering a clean energy generator.

Bruce’s initial attempt to resume his Batman guise fails spectacularly. As Alfred points out, Bruce has nothing to live for, putting on the suit and taking out motorcycle riding thugs is an empty thrill for him. Alfred tries desperately to stop him from going down this path but only serves to alienate Bruce further before leaving him.

Theatricality and deception are powerful weapons against the uninitiated.

But we are initiated, aren’t we Bruce?

When Batman and Bane finally confront each other, Bane dismantles him with ruthless efficiency and breaks him completely. Imprisoned, we watch once again as Bruce rebuilds himself. This is one of the core ideas behind Nolan’s Batman films, the idea that ideals can’t be reached without trying again after failure. As Bruce’s father and later Alfred say in Batman Begins “Why do we fall, Bruce? So that we learn to pick ourselves back up.” The difference here is that it’s Bruce Wayne and not Batman who is able to escape from Bane’s underground prison. Symbolically, Bruce is once and for all emerging from the well he fell into all those years ago and now he’s whole.

The reveal that Miranda Tate is, in fact, Ra’s Al Ghul’s daughter Talia puts much of the film in a whole new light. While the character has been criticized for feeling underdeveloped, this isn’t so once you realize that she and Bane are fundamentally two halves of a whole. Everything Bane does, he does for her; he is simply a mask that she wears much as her father relied on a series of avatars. When Batman escapes and defeats Bane, Bane cannot imagine how he escaped because it was something he was not able to do on his own. “Bane’s prison” is truly just that.

If there’s a true villain of The Dark Knight Rises, it’s the ghost of Ra’s Al Ghul; although dead, his legacy lives on in Talia and Bane. “There are many forms of immortality”, Ra’s says to him in a hallucination. Bane/Talia is able to do what Ra’s and The Joker sought to do over the last two films; plunge Gotham into total chaos and mob rule.

When Bruce returns to Gotham, he dramatically lights up a giant flaming bat. Batman’s status as a symbol of hope is restored in Gotham’s time of need. Batman not only inspires a demoralized police force to serve as his army, his influence is what pushes the previously self-motivated Selina Kyle into heroism.

In flying the neutron bomb away from Gotham City and faking Batman’s death, Bruce is able to finally accept himself completely and move on with his life. Although he gives up being Batman, he leaves his work in the hands of John Blake, someone just as a capable and perhaps better suited to tackle the social ills of Gotham City. In leaving his fortune and home to Gotham’s orphaned and at risk youth, Bruce Wayne the man becomes Bruce Wayne the legend, an institution for good on par with what he’s created with Batman.

If Nolan’s Batman films’ core conflict is “Can Batman be more than just a man?” then it’s answered in John Blake’s entrance into the Batcave and subsequent baptism during the last few minutes of The Dark Knight Rises. In Blake, we are left with something that is both certain and ambiguous; we know that he will use Bruce’s inspiration and resources to fight crime, but we don’t know what form that’ll take.

In the end, Bruce has succeeded at the task that has cost him the best years of his life, not because Gotham City is forever rid of crime (if anything, the implication of Nolan’s films is that this will never be an option, that crime is part of the natural order to some extent), but because he has created a bedrock foundation for future Batmen to watch over his city.