Trigger warning: This review discusses content including rape, pedophilia, and suicide.

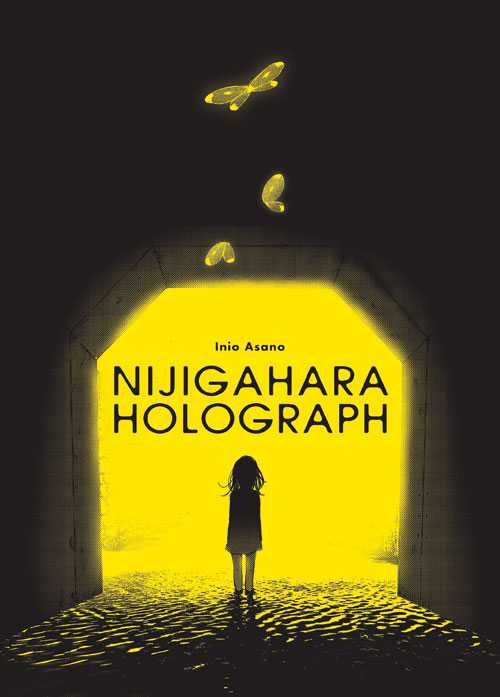

It is hard to summarize the plot of Inio Asano’s Nijigahara Holograph, which saw a U.S. release this month courtesy of Fantagraphics Books (with an English translation from Matt Thorn). The story takes place in alternate timelines, the distinctions between which are never clarified. Time hops and folds on itself and leaves you feeling jumbled, as though you’ve missed something important to bind the pieces together.

A fairy tale is told in the story, which forms the comic’s central logic: a girl warns a village of a monster that will destroy the world. The villagers fear her predictions, and sacrifice her to the monster to appease it. She is reborn to repeat the cycle. The monster grows larger.

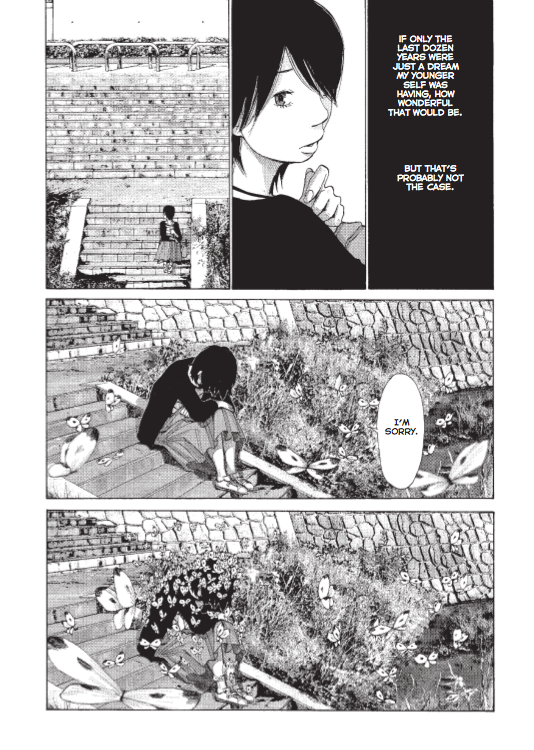

The sacrificial victim is Arie Kimura, sometimes a pale, pretty girl, sometimes an adult, sometimes her mother – it’s never clear if this is all the same person or not, but she forms a distinct visual counter to the rest of the characters in the story. Every moment of the story is bracketed by her multitudinous acts as sacrificial victim. She is murdered, she commits suicide, she is raped, abused, and killed again. Practically voiceless herself, spending most of the story comatose, Arie, or rather the violence she seems to elicit, haunts the consciousness of her peers.

In her key sacrifice of the story, bullied for spreading the frightening fairytale, Kimura Arie is pushed down a well by her classmates and lapses into a coma. The children go back to school, they fight, they grow up, and the world goes on while Arie sleeps. A strange infestation of butterflies plagues the city.

Inio Asano’s past works have always carried a tone of melancholy. He writes often about the frustration of modern life, but in a way that tends to highlight the arbitrary hope and happiness that humans can grasp at, flying in the face of all logic. Nijigahara Holograph, in contrast, presents a modernity devoid of optimism. The villain of the story is human violence, pooling just below the surface and ready to overflow at random, and every character has their own potential to become its source. The only hope comes in giving up, bringing about the end of the world or cutting off your own violent potential. Spreading her suicidal portent with the eerie placidity of someone who’s already given up, Arie ascends beyond the struggles of all her peers on Earth, again and again.

Arie is given so little voice throughout the book that her lack of presence is forced to become more powerful than her life ever was. Her own smiling unwillingness to live and thrive eats at everyone around her, struggling as they are to create arbitrary reasons to continue living. The characters make her into whatever guilt they carry, and attack her for it again and again. Even when she is described in life, Arie is too perfect, and the contradictory beauty and menace of the glowing butterflies directly mirror her. Both glow amongst Asano’s otherwise dark linework and unidealized figures. It’s an effect that makes the whole work that much more uncomfortable – the veneer of beauty cradling the story comes from this child’s abuse and tragic delicacy.

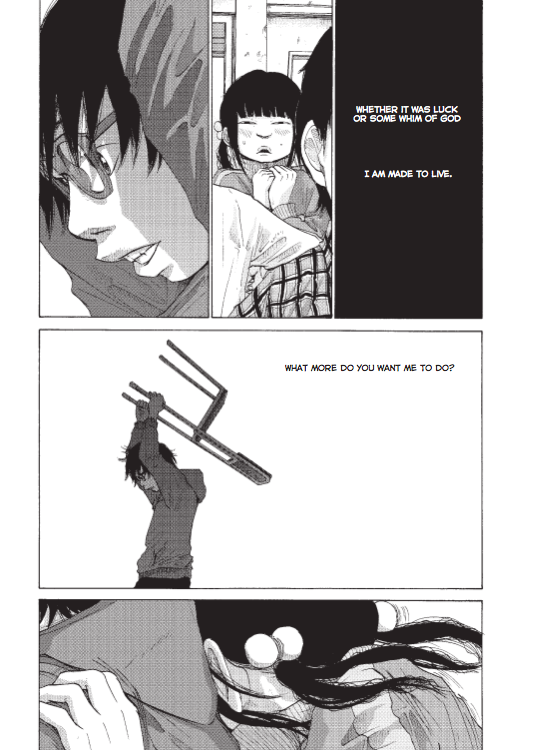

Asano’s artwork is masterful as always, and he adapts his richly emotional pacing well to Nijigahara Holograph‘s surreal tension. His pacing allows stretches of silence where the story is told only through physical interaction or visual symbols. He builds precise, detailed environments around his figures then drops them out entirely in the next panel to focus on a facial expression.

Asano’s unique voice in past works has hinged on a nuanced and very human portrayal of his characters. Everyone has their attractive characteristics and their flaws, and they react to events with an individual internal logic. Yet the main players of Nijigahara Holograph seem to be lost in extremes – you have the passive victim, the obsessive savior, and the obsessive rapist. The main character and narrator of the book explodes into frantic violence periodically in ways that make seemingly little sense. In some secondary characters, however, Asano’s nuance shines, and we receive moments of clarity in the hectic timeline. Arie’s teacher, injured by Arie’s molestor upon trying to save the girl, struggles with conflicting motivations to protect her students or insulate herself from their problems. She shouts her rage about being dragged into the child’s trauma, and still fixates on the Nijigahara site years later. Another character, a rival female classmate, is locked into a perpetual loop of romantic competition with Arie. First this motivates her to participate in Arie’s tumble down the well, then it comes terrifyingly to the surface when her current lover reveals himself as Arie’s childhood rapist.

Instead of the basic coating of gruesome violence one might expect from a horror comic, an overwhelming majority of the violence in Nijigahara Holograph is specifically sexual and directed at women. Yet the narrative purpose of this violence seems disconnected from the sexual content. It is as though sexual violence was simply the first thing to come to Asano’s mind as a way to express an undercurrent of violence throughout the world overflowing into a animalistic crime of passion. Asano’s rapists attack the world metaphorically by assaulting this woman. Why is it necessary for Arie to be so specifically destroyed throughout the story? Even if it was necessary, surely the same violence could be conveyed in less explicitly graphic visuals. Beyond making the story uncomfortable nearly to the point of being unreadable, the sexual violence misdirects attention from the already tenuous purpose of the story.

Instead of the basic coating of gruesome violence one might expect from a horror comic, an overwhelming majority of the violence in Nijigahara Holograph is specifically sexual and directed at women. Yet the narrative purpose of this violence seems disconnected from the sexual content. It is as though sexual violence was simply the first thing to come to Asano’s mind as a way to express an undercurrent of violence throughout the world overflowing into a animalistic crime of passion. Asano’s rapists attack the world metaphorically by assaulting this woman. Why is it necessary for Arie to be so specifically destroyed throughout the story? Even if it was necessary, surely the same violence could be conveyed in less explicitly graphic visuals. Beyond making the story uncomfortable nearly to the point of being unreadable, the sexual violence misdirects attention from the already tenuous purpose of the story.

Horror usually contains a menace, and characters attempting to flee from that menace. Through strange, violent episodes and a confusingly abstract, cyclical timeline, Nijigahara Holograph asks the question: what if that menace is internal? What if it is the characters’ own potential for violence that they are trying to escape from? How do you try to survive when ultimately your only defense method is to kill yourself? Inio Asano creates a bleak, tumultuous world to present us this conundrum, but leaves us on our own to create answers.