At the risk of sounding like every dateless, neckbeard sporting, fedora enthusiast finding himself without a date on a Friday night, what is the appeal of assholes? Specifically, why do we as a society seem to exalt the lowest common denominator when it comes to our fictional heroes? Why do people write think pieces about it?

With DC’s Sun God patriarch snapping necks to solve problems and Marvel’s resident boy scout lighting up the screen this week in his own excellent foray into summer blockbusting, there seems to be a pretty divisive split between what it means to be a good guy. Somewhere in that middle is a grown man wearing jorts and brightly colored t-shirts hugging small children at scripted sporting events.

If you talk to the average moviegoer, or comic reader (or wrestling fan) it’s been a very long time since someone standing up for what’s right without being a sarcastic, violent asshole about it was someone we wanted to support in media. Die-hards may have been outraged at the climax of Man of Steel, but the number of people who squealed with glee at Superman cold murdering someone to solve a problem is probably a lot higher than one might think. Not surprisingly, one particular Vulture article addresses this head on, advocating that a hero like Captain America is only interesting when he’s portrayed as a prick.

Captain America: The Winter Soldier painted it’s titular hero in broad, relatable strokes, presenting him as the very best of the Greatest Generation, a man who lives by (and nearly died for) a moral code that is as difficult to abide by as it is easy to mock. It’s reductive yet commonplace to dismiss heroes like Steve Rogers and Not Zack Snyder’s Clark Kent. People negate their worth both as characters and myths by deeming their goody-two-shoes nature as boring or predictable.

In professional wrestling, fans say the same about John Cena, a sort of postmodern Hulk Hogan who replaced saying your prayers and eating your vitamins with the triumvirate grail of hustle, loyalty and respect. He’s a friendly, upstanding guy who abides by the rules and devotes all of his free time to hanging out with Make-A-Wish kids. Surprise, surprise: people fucking hate his guts. Some of that disdain comes from stagnation. His character hasn’t evolved much in the last decade, but, as with the aforementioned superheroes, people rarely criticize these “supermen” for not evolving. The crux of their scorn is born from a fundamental lack of admiration for an adherence to lofty standards.

Why is that?

Two and a half years ago, I ranted on Twitter about Superman and why it makes no sense for people to dislike him the way they do. My general feeling then was just that people had some sort of hard line aversion to identifying with someone who always tries to do the right thing, as though great power and great responsibility were peanut butter and arsenic. I mean, I get it. I used to think Captain America was weaksauce milquetoast and that he would be way cooler if he was more of an antihero. For context, however, when I thought this, my favorite filmmaker was Kevin Smith, my favorite band was Limp Bizkit, and I was a couple of years out from being really into Mark Millar. Luckily, time is less of a flat circle than Rustin Cohle would have you believe.

The point is, I grew up. I stopped being a world-hating boychild whose blood type was misplaced anger. I stopped conflating negative character traits with positive signifiers. One of the reasons people seem to criticize optimistic superheroes is because they aren’t realistic enough, but I think they’re missing the point. We created superheroes because we needed something “unrealistic” to save us. Realism is relative. The argument that a superhero who is a bit of a dick all the time is more real or interesting than one who is decent and upstanding all the time is complete bullshit. You know what’s boring? A lack of conflict.

Think of every independent movie you have ever seen about malcontent twentysomethings standing around being pithy and passive aggressive to one another with improvised dialogue and no budget. When someone criticizes the filmmaker for the story being bland and the characters being unlikable, their response is normally that they’re drawing from “real life.” Somehow, they feel their stories are better than Hollywood shlock where the hero beats the villain and gets the girl because “that never happens in real life.” The problem is, it never happens in their lives because they aren’t fucking heroes. They’re selfish, myopic assholes who can’t deign to fathom anything more aspirational than the pathetic muck of their own solipsist existence.

So, too, are the detractors who are unimpressed by an unkilling Superman, a Captain America who doesn’t lean heavily to the right, or a babyface fighter who just wants a good clean win. If you don’t like a Superman story because he has too many powers and smiles too much, it’s because the story you are reading isn’t challenging him enough, nor does it have enough variety of content. If you think Captain America is too good a person, then you probably don’t know very many good people. You’re not mad that John Cena is too nice. You’re mad that he wins all the time and doesn’t compete in believable fake combat.

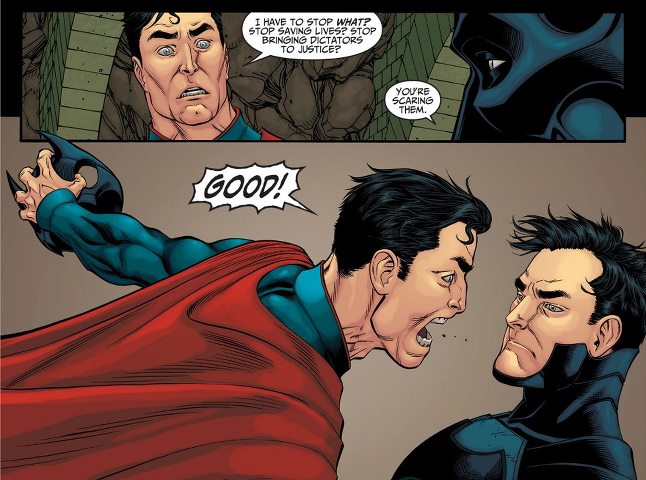

For most comics fans, DC’s adaptation of the Injustice: Gods Among Us video game is a trash masterpiece that exists solely for ribbing purposes, but I don’t have enough digits on either hand to count the number of people, in real life, who have told me how much they loved it, not because it is laughably awful, but because they loved it’s portrayal of Superman.

Yes, that Superman. The one who straight up murders the shit out of The Joker and then outs Batman’s secret identity on Twitter. This is a real comic that was published and there are people who enjoy it because, to them, it finally makes Superman cool. We’re more than ten years removed from Joe Kelly’s “What’s So Funny About Truth, Justice & the American Way?” and people still think Superman is lame if he isn’t basically an out of control Wildstorm parody of himself?

It’s telling that when wrestling fans complain about John Cena, he’s often unfavorably compared to The Rock, the Attitude Era megastar turned action hero who preceded him as the face of the WWE. To be fair, Cena is by no means perfect, and is considerably more fallible than either Supes or Cap, but there is an undeniable sweetness about him that endears him to the youth in a truly inspiring way. Of course hardcore viewers lament that he replaced a guy whose primary function was talking in the third person and suggesting people shove things up their own asses, sideways.

Were these people all bullied as kids and then developed some weird Stockholm syndrome for their respective wedgie givers? We can’t look at a guy who can fly around the sun, or toss a shield (or clothesline real good) without wanting to extrapolate those strengths to their absolute worst application?

Captain America doesn’t need to be a xenophobic John Wayne to be entertaining. That just isn’t the character. I don’t think he needs to be a leftist soapbox either. Sure, he was a soldier in WWII, and yes, he wielded a gun, but guess what? Jack Kirby designed him with a shield. Not a sword. Not a lance. A fucking shield. Do you really want to belittle that inspiring an image by reducing him to Fox News Punisher? This isn’t me saying my favorite version of a character is better than your favorite version of a character. I just think we really need to question whether or not the term “weaponized homophobia” is something we want to have to type when describing the fictional beings we call our heroes.

My biggest beef with Mark Millar’s often referenced take on Captain America isn’t that Ultimates is a bad comic. By no stretch of the imagination would I compare it to Injustice or Ultimatum. It has it’s strong points (largely Bryan Hitch’s art) and I respect that it’s an alternate interpretation of the mythology designed to attract new readers, but who were these new readers Marvel felt they needed to reach? Did Millar focus group this with a small group of horny, pissed off 12-year-olds? Every single moment Steve Rogers appears in a panel feels like it was rewritten by kids angry enough to swear but afraid their parents would catch them, an actuality that would legitimately explain why Captain America refers to people as “meatball’ and “jerk.”

To quote one of the aforementioned Kevin Smith’s characters, “Nobody talks like that. That is fucking baby talk.”

What’s so interesting about a close minded, hyper-violent manchild with superpowers, kicking people in the nuts and emphatically pointing at his own forehead after eviscerating an alien? Why is that so much better than the way Chris Evans has portrayed the role in the MCU? I’m not against a more conservative take on the character. Remember in The Avengers when Steve says “There’s only one God, and he doesn’t dress like that?” That was a smart line. It furthered the feeling that this was a man from another time having difficulty being thrust into this insane new world. You know what was great about it, too?

HE DIDN’T SOUND LIKE A COMPLETE FUCKING ASSHOLE EVERY TIME HE OPENED HIS MOUTH.

There’s just no earthly reason to need to dumb down or compromise these characters to appeal to some imagined Muscle Milk & Bud Light fringe contingent who would support these properties if only they were brought down to their pathetic level. That’s not some nerdy, pent up jock hate, either. I just personally imagine that the same person who would rather read or watch a superhero who kicks the shit out of someone doing graffiti is someone who would think it was a good idea to get their protein for the day in while knocking back beer that tastes like stale water.

Captain America wouldn’t be more interesting if he were a jerk. He’d just appeal to more people who don’t need superheroes in the first place. Superheroes are supposed to save us, not reinforce how shitty some of us are.

It’s okay to admit that we want more from fiction. Real life isn’t so hot, guys. Turn on the news. There’s no weakness in acknowledging a need for heroes who are better than us. It gives us something to reach for.

Thank you for this. Seriously.

Is there a way we can have this tattooed on Snyder and Nolan’s heads?

I genuinely think Christopher Nolan’s perspective on “realist” superheroes is more understandable, as its in line with how he approaches storytelling in all of his films. I just personally didn’t dig Snyder’s take on the material.

In Nolan’s defense he was the one guy that DIDN’T want that ending in Man of Steel. That was all on Synder and Goyer.

I disagree with this on a multitude of levels, but I don’t have it in me to give the reply I really want to. I’ll just say this. Superman is boring, as a man, a character, whatever. I’m sorry, but someone who is not only damn near invincible, but super strong, fast, has laser eyes, x-ray vision, etc. and on top of that is the penultimate good guy whose only real flaw is the weakness of the people around him is not something you can aspire to. It’s impossible, and little boys thinking we can be superman is the reason a lot of us go out and do the stupid shit we did as kids. Captain America, I love, because ‘Murica. What I want in a hero is a realistic person, with unrealistic powers. That’s what I mean when I say Supes is unrealistic. I mean, the guy moved a planet. With just straight up upper body strength. Ugh.

Thinking that Superman’s only flaw is the weakness of the people around him is a little bit off, I think. What I love about Superman is that he represents someone who always tries to do the right thing, and I think that’s admirable. Being more like Superman doesn’t mean you aspire to be perfect. It just means you aspire to try to be better in any given situation. I do think that the absurdity of pre-Crisis power levels makes Supes a little ridiculous, but I think in a good story, those things are just window dressing.

Some of the best Superman stories revolve not around his invulnerability or his superpowers, but around the simple idea of Superman trying his best to help and inspire people – and, in a sense, how he can’t help everyone all the time.

Oh sure, Superman can save a bunch of people, but he can’t save everyone. One of his greatest virtues (his compassion for others) makes for his biggest weakness. The exploitation of said weakness presents better opportunities for storytelling than focusing on trying to “hurt” Superman via physical beatdowns ever will.

I’m a bit unclear on your point in regard to kids doing dumb things. Is it because they’re emulating Superman’s abilities, or because they’re emulating his adherence to doing good?

My reason for liking Cap and Superman is simple. They don’t need a reason to be a good person. Cap was already busting his balls to be a soldier before he received the serum. Superman could have just as well started his own, one man version of UPS, or sat on the couch, watching Matlock.

My best friend is a homicide detective. No one killed his family, or anything like that. He’s just a really good person, and that’s how he most enjoys using his talents to help people. He volunteers for everything, especially if it involves helping children. I’ve also known him to get cash for people who are legitimately down on their luck so they have a place to stay, feed their families, etc. I didn’t know he did that until one of the other officers ribbed him about it – and I’ve known him for almost 30 years. His wife works with troubled kids because she wants to help. She advocates for them instead of putting them down. They both put in tons more hours than they should. Their careers aren’t about punching the clock. They’d still be good people trying to help out in some way if they were in other professions.

They’re pretty interesting to me.

If you don’t like Superman stories, you’re not watching them for the right reasons. Contrary to popular belief, the appeal of Superman stories isn’t to see him kick somebody’s ass, it’s to see him to the opposite. Superman is one of the most powerful beings in the universe, and what does he do with that power? He stops bank robbers, he rescues kittens from trees, and he also saves the whole of reality – all without killing. No task is too big or too small for him. Good deeds are good deeds, and his business is doing good deeds. I personally love how some of the best Superman stories center around his no-kill conviction. He’ll be faced with a problem that could be solved in 10 minutes by just killing the bad guy, but he knows there’s another way, and he’d rather die trying to resolve the conflict that way rather than take the easy road and kill the baddie. “What’s so Funny About Truth, Justice, And the American Way?” is one of the best examples of this. Conflict doesn’t always have to physical, and is often much more interesting if it isn’t. Superman’s appeal comes from the fact that he’s an insanely powerful being who refuses to lower himself to “bad” behavior, even as a means to a “good” outcome. Real strength often comes from having power and not using it. If you want to see some edgy, ordinary, “realistic person with unrealistic powers”, you don’t want to be watching Superman. He’s the paragon of good, not the paragon of angst-ridden teenagers.

When you talk about John Cena, you mention all the unfavorable (and, I’ll say it, unfair) comparisons to The Rock. Allow me to explore that a bit.

John Cena comes off as a braggart; one of his catchphrases goes “The Champ is Here” and he has continually brought up his “legacy” as of late. Whereas both Cena and Rock did this same schtick, Rock’s version of the act came off as somewhat more endearing because of his innate charisma, tight delivery, and lack of complete pretense (Rock knew he came off as an asshole braggart and never once tried to deny otherwise, even as a “good guy”). Cena, on the other hand, tries to have both sides of the coin; he does the asshole braggart schtick under the pretense of his “virtuous good guy” persona. That pretense turns a lot of fans off to Cena’s act because it comes off as hypocritical.

Get beyond that Cena/Rock comparison and you can see other problems with the Cena character – including his lack of evolution (something you decry in this article).

I’ll talk about his fallibility first. Yes, Cena loses matches – but he rarely loses them 100% clean. He rarely ends up affected by any loss in any meaningful way; even after he lost to The Rock at WrestleMania 28, he never seemed affected by that loss after his “admission” of losing to the better man on the following night’s episode of Raw. Combine those two factors with writing that “protects” the Cena persona as much as possible from looking fallible or even remotely afraid of anything, and you have the recipie for a character whose “overcoming the odds” feels even more artificial than normal in the context of professional wrestling.

Making this point allows me to transition into a discussion of Cena’s lack of evolution – and it presents the opportunity to do a much more apt (and current) comparison in the form of “John Cena vs. Daniel Bryan”.

Take a look at the evolution of Daniel Bryan’s career since his debut on NXT in 2010: you can see shifts in his character, however subtle, over the course of the past four years – from his initial NXT Rookie run to his United States Championship reign to his World Heavyweight Championship reign (you know, the one that ended in Eighteen Seconds) to his work as one-half of Team Hell No to his current run as the “anti-Authority” good guy. Bryan’s evolution works because of its complete lack of pretense: even as a villainous champion, the Daniel Bryan character made no apologies for the way he acted and never once tried to pass himself off as a “hero” – and vice versa for his current good guy run (Bryan does a few “villainous” things here and there, but WWE takes great pains to justify Bryan doing them so that he comes off as more of an “underdog hero” than anything else).

When you look at the character evolution of John Cena in comparison, a simple fact becomes clear: Cena stopped evolving almost immediately after he won his first world championship at WrestleMania 21. An old writing axiom I picked up in my reading time (essentially) says a hero either changes because of what the world does to him or changes the world because of what he does; the axiom means that a story’s main character doesn’t necessarily need to evolve if they can change the world around them through their actions. The John Cena character hasn’t evolved or changed the world around him in a long, long time.

Cena’s last major character evolution happened in 2005 (when he dropped his “white rapper” act and turned into the psuedo-Marine “All-American good guy” character we know and…well, at least tolerate these days). After that character change, WWE pushed Cena as the next incarnation of Hulk Hogan – and that meant Cena ended up in an endless stream of “Monster of the Month” storylines where a nasty villain would try to defeat Cena only for Cena to eventually “overcome the odds” and win in the end. With the sole possible exception of the Nexus storyline (which WWE botched all to hell almost exclusively based on involving Cena in the storyline), Cena has never played a role in a storyline that somehow “changed the face of WWE forever” or captured the attention of the world in such a way that it made him a character on par with legends such as Hulk Hogan and Steve Austin. In contrast, Daniel Bryan did exactly that when he ended up in his feud with The Authority, and said rivalry helped lead to WrestleMania 30 – a show where WWE seemed to go through a “changing of the guard”, due in part to Bryan’s victories over Triple H and the duo of Batista and Randy Orton (both two of Triple H’s old running buddies).

WWE also insists on holding Cena up as both a superhero and an “underdog” at the same time – after all, WWE needs us to believe Cena sits in some form of peril for us to care about the outcome of his matches/storylines, and that peril typically comes in the form of an attack on Cena’s character (e.g. Kane’s “Embrace the Hate” bit from a couple of years ago, the current feud with The Wyatt Family). WWE booked Cena “overcome the odds” and avoid compromising himself to the point where nobody with a sense of history believes WWE will ever put Cena on the losing end of a storyline and change the character as a result. Kids may enjoy the Cena character because he never loses and always looks like a hero, but for adult fans of the artform of professional wrestling – fans who cheered their asses off when Daniel Bryan won the main event of WrestleMania 30 – the character comes off as phony and pretentious, especially in the moments where WWE tries to make them believe the Cena character sits in any form of true peril.

As for the last real problem with the Cena character, I’ll quote Tumblr user falseunderdog regarding Cena’s decision to apologize for “losing his cool” in his WrestleMania 30 match against Bray Wyatt (read: using a steel chair to nail another member of the Wyatt Family instead of Bray himself):

People call for a Cena “heel turn” all the time; while that might re-ignite interest in the character from that segment of the audience, it won’t fix any of the fundamental problems associated with the heroic Cena character – problems that could end up haunting whoever WWE decides to turn into “the next Cena”.

I can only pray that those problems don’t end up transferred to Daniel Bryan in a few months.

I actually agree with nearly everything you have said about Cena here, particularly his unchanging persona. I used to despise him, for the longest time, and only in the last year and a half or so have I come around to being a bit of a mark for him. His ring work seems to be more consistent, outside of the usual third act power up into AA finish he relies on, and there’s a little bit of veteran moss growing on that old tree that I like.

What I really hope happens with his character next is what is happening with Triple H. Hunter has transformed himself into a real heel manifestation of the so called IWC’s perception of him backstage, and in doing so, has become a truly captivating and entertaining boss level villain. With Cena peppering promos with references to the future of wrestling having to go through him, I want to see him evolve into being the unstoppable old guard who represents a glass ceiling for midcarders trying to make it to the main event scene, and making his moveset more like an All Japan super brawler, as Brandon Stroud has alluded to in his excellent Best and Worst of Raw column.

Typical IWC nerd talking points.

I’d still say Captain America is a better hero when he starts out a jerk and learns to be a better hero. It’s one of the things I’d say really differs from Superman compared to most other popular heroes. Supes seems to have been “born good”, we don’t ever see him tempted by evil or learning to use his powers, for the most part. It’s like being a hero is part of his genes, not part of his personality.

You know what’s better than both an upstanding hero saving the day AND a bunch of passive agressive twentysomethings standing around? A character that screws up and then tries to fix it. Someone who actually comes out at the end of the day a better person than they started. I think Superman’s problem is that he has so many things stacked in his advantage, the act of him screwing up requires deus ex machina to the extreme. He has no greed, no avarice. There’s few challenges that he wouldn’t be able to overcome easily.

Really, it’s not that Superman is boring or badly written, it’s just so much harder to show character growth or development in his stories compared to almost everyone else.

(That said, I agree about the stupidity of just throwing flaws at a character like they’re tassels until they turn into petulant manchildren.)

Cap starts out a jerk? I think you and I have read different Caps over the years.

He is not a jerk at first. Cap genuinely feels that becoming a soldier against the Nazis in WWII is the right and good thing to do. He isn’t a jerk about it, quite the opposite, and tries to be a hero but isn’t able to.

That’s the difference between him and Supes that I might be able to see as to why you think Cap is more interesting.

But he does not need to learn to be a hero. Steve Rogers just has to gain the power to do so.

Which is also why I like Superman just as much: He decides of his own volition that being a hero is the good thing to do. His powers are just a means to get him to fight deities and aliens with powers far beyond humans can do, his humanity however comes from his supporting cast: Lois Lane, Jimmy Olson, Perry White… And that’s where he is most interesting. Which DC editorial do not seem to understand.

I’ve never understood the backlash on Man of Steel and I think it’s a bit disingenuous to call what he did cold murder.

In the movie he is put in a situation where he has to choose between killing the last of his kind or allowing others to be killed by inaction. That’s the scenario. And that’s precisely the scenario that you put the Man of Steel in, a no win situation where you have to choose. In the end he chooses the many over the one and saves a planet.

If you say they shouldn’t have put Superman in that scenario: That’s OK if you don’t want your heroes to be challenged to their very core. I still think this new Superman is a boy scout, but maybe now he is a man, making impossible decisions.

No a real hero, in the Superman mold, is put in a no-win situation and makes the choice that turns it into a winnable situation: kill or let be killed becomes save everyone.

(Spoiler Warning) I think you have a point, there. In the movie, as the villain was talking about how Superman had destroyed his reason for living, I was thinking about how Superman could have talked him down from that. He could have said, “No, now _I_ am the last of your kind left. I am your reason for living. Work with me to help the human race, so Krypton can live on in us.”

It might not have worked, but I think it would have been good to try. He could have taken the two choices and made a third. I think Captain America did that to some extent in the second movie. The Chris Evans Captain America is now my favorite superhero. He’s just got so much integrity, sincerity, humility, and kindness. The other Captain Americas don’t really do it for me.

I’m with you all the way on this one. I think a lot of the criticism of Man of Steel is poorly considered, and some of the rest is disingenuous.

Superman’s killed Zod like fifteen times over the years, and suddenly it’s a problem when he has a good reason for once plus Zack Snyder’s name is on the film.

Let’s talk about some of the basic realities of this kind of fiction. Number one: it’s fiction. This stuff isn’t only outside of the real world because it features impossible supernatural powers and ridiculous costumes. It’s based on a cultural lie, and the entire genre has its roots in propaganda.

Captain America was created during wartime. The propaganda machine that characters like Captain America and Superman represent is an artifact of a bygone era. Musclebound characters inspired by wrestlers, wrapped up in the American flag should seem quite hollow today. We’re living in the post-9/11 era. Politicians with exploitative agendas have used false premises to rally the American people to devastating wars that have cost thousands of lives. The United States of America is no longer the last minute savior of World War II, or the last bulwark against communism. Now the U. S. is seen worldwide as an aggressor that shamelessly invades other countries as the muscle for international oil barons.

Superheroes in general are based on a flawed premise, and they certainly don’t constitute role models for children or anyone else. If they truly existed in the real world, they would constitute a serious problem. Citizens are not entitled to costumed vigilantism. We have more than enough law enforcement in the United States, and the criminal justice system has now been given so much power that the U. S. is the leader in incarceration. The premise that we would ever need a violent lunatic in a bat costume to patrol the streets is ridiculous.

There was a time when Superman was briefly used as a symbol of opposition to corporate greed and political corruption, but that was mostly dependent on whatever reimaginings of Lex Luthor were implemented, not any change in the “hero” character.

Characters that promote the use of violence to solve problems are not useful to society, nor do they represent “good guys” in the modern world. They’re just selling another version of might-makes-right.

The criminal justice system in the United States is broken. People don’t react to police as protectors today. When they see a police car out in the street somewhere, it’s like seeing a shark fin in the water when you’re at the beach. People have learned to be afraid of law enforcement. More and more and more innocent people get railroaded into prison or into probation they cannot afford every day. The victims of recreational drugs are jailed. The concept of mens rea has been thrown out the window in our system. This country is rapidly degenerating into a police state. The last thing in the world that we need is costumed idiots rounding up more hapless people and putting them in prison. Enhancing and reinforcing the “us and them” mentality of our society is not a service to society. Comic books aren’t creating heroes. They’re leading everyone astray in a world that should be promoting understanding instead of accusation and condemnation.

Action movies and comics are fun. They’re not really morality plays. As a rule most of the authors of these works portray a world of moronic black and white thinking where being the good guy or the bad guy is defined by who you sock in the jaw, and the option of not socking anyone in the jaw doesn’t enter the formula.

The few writers who come up with just the slightest additional level of depth in these stories get heralded as great geniuses, and they’re barely scratching the surface of what’s possible with the medium.

What’s ridiculous abour supermen? The fact that you even have to ask this question means you already drank the kool-aid. I was a comic book fan for many years, and I’m overly familiar with the genre of superhero comics, and it’s obvious that superheroes are exactly what’s holding back the entire medium of comics in America. In Japan they have comics of every conceivable genre, but the United States still just wants to show men wearing capes and underwear on the outside of their trousers.

How cynical and sad you are.

I’m a bit of an optimist, and I see George’s point. Real-life vigilantism is problematic (Remember George Zimmerman vs. Treyvon Martin?), and maybe we need different sorts of heroes. Insights about the imperfections of our heroes and ideals can trigger the beginnings of improvement, of rethinking. If we don’t need vigilante heroes, maybe we need the sorts of heroes that help during natural disasters, or teach our children, or create scientific advances, or even “fight the man.” Cynicism isn’t someone saying, “this is a problem.” Cynicism is someone saying, “this is a problem that will never change.” Even if you disagree with his conclusions, George Edward Purdy is not necessarily a “sad cynic.”

I largely agree with the overall take on these things. I remember my first antihero. A guy that people idolized in spite of the fact he didn’t want it (Thomas Covenant) and was an asshole. Which reminds me of Greg House, who is a hero because he saves people and not because he likes them.

So after 30 years of seeing anti-hero stories play out, I see your point. I’ve been reaching for a believably good character for something like the last 12 of them. I agree with Cole: Superman seems to be born to be good; I love the new Captain America for his uprightness.

The best stories, like you said, need conflict. It seems in this day of everyone out for themselves, there would be plenty of conflict for an “American” hero who wants to protect life AND liberty. I have to go watch some Captain America now. Thanks again.

P.S. Now, about that Wonder Woman movie….

Good point about House.

Conflict is fine, but when it’s half-assed, well…THAT’S the problem. Unfortunately, MOST people in Hollywood don’t understand this. Those who defend Man Of Steel stick to one or two common excuses:

1) He’s only been Superman for, like, a DAY!!!!!!1

True, but he’s been a “alien-living-as-a-human” for, what, 33 years? Then again, Costner REALLY wasn’t “Parent Of the Year” material, now was he?

2) He’s killed Zod before!!!!!11!!

True, but just because he could (and has) doesn’t mean he should. Some of my customers commented that the act was setting up the sequel. I asked “What if there ISN’T a sequel? THIS is the Superman that kids today are going to be stuck with.”

And, scyllacat, I think you’re better off that they don’t do a Wonder Woman flick. LORD KNOWS how they’d mess that up. Then again, we might have some indication two summers from now.

To some extent I disagree. I felt that if the story in Man of Steel was handled better the moment of where he killed Zod would’ve had more gravitas. If they depicted a more hopeful and optimistic Superman, in addition to watching Superman try his hardest to protect the citizens of Metropolis (even though he probably could’ve dont much), then audiences would have been even more impacted when he was forced to kill Zod as an absolute last resort.

You also have to consider that sometimes there isnt always another way, though we like to think so. One example that comes to mind is from the Death of Superman story arc. Before the final blow with Doomsday, Superman basically mentions that if he didn’t take the monster down before he was killed, then no one would be able to stop him. In that situation Superman made the decision to “kill” Doomsday while sacrificing his own life. Man of Steel depicted a similar situation. As Zod was shown to have become increasingly stronger and adapted to his new abilities, he would have eventually outmatched and possibly killed Superman. With no kryptonite or any outside help Superman was in a very tough situation. Sure he could’ve tried to talk him down, which would’ve been nice to see, but Zod wanted his head and everyone on Earth dead. What else would you have him do?

Btw, I’m not quite following your last point since there is a sequel. Sure, for now this is the Superman kids are stuck with, but if the Man of Steel franchise is handled correctly, kids will be able to watch Superman grow and change.

It is _so_ good to know that we’re not the only people who hate the “jerkification” of iconic heroes. Thank you for this.

I find that the overreaction to purehearted heroes is a frustratingly surviving relic of something which no longer exists. There’s this notion of our collective sense of childhood that the heroes sold to us by adults were just stealthily teaching us to mindlessly obey authority and follow every rule without questioning it. From the same place comes the idea that if we all do this, everything will be fine and there will be no problems. I would say there’s an element of truth in this for those of us raised by television, but the thing is, people have been attacking this idea pretty much since its inception, and practically no one buys it now, if they ever did. Our heroes for ages have been people who defy these sorts of rules, which led us to believe the old-fashioned heroic types were lame and corny.

The problem with this, one of many anyway, is that the bar keeps getting raised, or lowered as the case may be. Our heroes drift slowly but surely into the realm of antiheroes and finally into the realm of villains. Americans seem fond of particularly vile protagonists nowadays, and that says a lot about us as a society. We want monsters to do what they must to make us feel safe again. But that’s getting a bit off topic. The point is, people still act like our society is propping up the boyscouts, when it’s pretty clearly the other way now. We prop up the bad boys, and even the flat out bad guys.

I am perfectly fine with fiction taking its course and not being stuck with one type of protagonist, but as to whom I admire, it’s always going to be the heroes with the strongest moral centers. And in general, when people tell me they’d rather have someone around to do the bad things and that’s what they want to be like, my considered opinion is they haven’t met enough people like that in real life. By and large, those people aren’t looking out for us. Nothing they do is for us. It’s for themselves. If you happen to benefit from their self-interest, fine, but if you’re in their way, they’ll squash you too, have no doubt. We don’t need to admire our monsters, nor should we drag our heroes down into the muck with them. As for me, I’d rather we tried to ascend, even if the heights are a bit unrealistic or difficult at times.

I think it’s possible for someone to be born with the intent to do good, the intent to be the best person they can be and to help the world. In that situation, character development can come in the improvement of the EXECUTION of that intent. Honestly, there are plenty of times when I and others mean well, but end up messing up royally. There are also times when characters (and real life people) have to make hard decisions, and that can be character-building as well. Characters can grow in seeing a deeper complexity in the world, forgiving themselves and others, going through hardship, being broken and then healed, coming to a deeper understanding of love, etc. while still being really good people from beginning to end.

This would be the part at the end where I would start to slow-clap and then everyone starts slow-clapping their asses off for you buddy. Really, just WOW… Well done.

This is quite an insightful article my friend Phil hipped me to.

It’s about how consumers of media long for art that satiates their revenge fantasies rather that art that inspires them to reach their highest selves.

The biggest flaw of the article, I think; or, at least, what I think this article fails to address is all of the questions it raises. The author seems almost afraid to venture a guess.

But I don’t believe I have to guess. All of this stuff–whether it be goody-goody superheroes or “badass” anti-heroes–is rooted in a particular brand of Whiteness.

Even when Superman and Captain America, among others, were written as aspirational forces representing all that was good and moral, they were still often operating as tools white supremacist indoctrination and patriarchal domination. They were still appealing (and still continue to appeal) to the very base desires of sometimes-straight white men/boys (and people who want to be white men/boys) to see themselves as “saviors,” which is another way of saying “superior.”

If you want to know what these heroes, in whatever incarnation, actually represent, ask black or brown people. Or some women. Or some queer people.

These are heroes that called Chinese people “gooks” and Japanese people “nips.” These are heroes who had buffoonish minority sidekicks as comic relief. Not a black depiction showed up in these stories unless it was to show black people as deficient in some way. These are heroes who condescended to the women in their lives and demanded their domestication. These are heroes who often fought against “evil,” “deformed,” “effeminate,” and “dark” villains. These are heroes who fought “valiantly” in World War II and returned to Jim Crow America and neither did nor said anything about the inherent injustice of it; they, in fact, pretended those injustices didn’t exists (and so, we were also supposed to pretend, like we do today, that they didn’t exist) and they were intentionally left out of every panel in their stories–erased so that “goodness” and “Whiteness” could, by default and omission, function as synonyms and, therefore, indoctrinate generations of children and adults across racial, gender, and sexual lines. (This is what I believe is at the root of the panic of John Stewart being positioned as the “main” Green Lantern, or a black Human Torch, or a Wonder Woman film.)

As James Baldwin once put it: “In the case of the American Negro, from the moment you are born every stick and stone, every face, is white. Since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose you are, too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, and although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

So while I get the author’s point (and it’s a compelling one), I don’t share it. Because in some way, shape, or form, these characters, from my vantage point, have always had darkness in them; have never held the moral high ground; were never anything I thought was morally worthy of aspiring to be; have always been narcissistic and violent; have always posed a danger to innocents; have always been arrogant. The goodness and innocence they supposedly represented was always suspect and easily unraveled. Their aspirational values never included treating the marginalized as human beings unless those marginalized looked and/or thought exactly like them. Their aspirational values are inextricably tied to the American pathology which demands that America and a certain subset of Americans be found innocent of their numerous and perpetual crimes. More than innocent, one must believe that the crimes, in fact, never occurred. It is not coincidental that these heroes are draped in American flag drag. What these characters are telling us, or, at least, what they are telling *me*–what they were telling me from the 30s and 40s when they were created and what they are telling me now–is “Whiteness Saves!”

But the record shows that Whiteness does anything but.

When people begin to get nostalgic about these characters and imagine some golden age of heroism that, for me, never existed (like they do about the 1950s sometimes), I like to remind them of the lynchings and the terrorism and segregation and the G.I. Bill and black soldiers who fought in American wars returning home to have dogs loosed on them and water from hoses shot in their faces and Japanese internment camps and women who were told to get back in the kitchen and Emmett Till and how Superman and Captain America couldn’t give a single fuck about any of that. I like to remind them that Superman and Captain America are, in fact, indicted by their silence and their continued claims of innocence despite the blood on their hands. Because Superman and Captain America are only real to the extent that they represent the consciousness and the consciences of the people that created them. The imaginations are one and the limitations are shared.

Why, the author asks, have these dark, anti-heroes become so popular and appealing and why are goody-goody heroes thought of as boring?

Maybe it’s because Americans have finally learned to stop lying to themselves about the nature of what it means to be an American and have reconciled embracing the truth that these supposedly aspirational characters were mildly successful at hiding. Superman breaking a man’s neck is the most honest thing American myths have ever said about what America represents. This is the most honest form of that awful word Americans use so readily and haphazardly, but have no idea whatsoever as to its meaning: progress.

Baldwin again; he’s talking about film in particular, but I believe this applies to any form of America media in general:

“I don’t wish, here, to belabor a point to which we shall, presently, and somewhat elaborately be compelled to return: but *no one*, I read somewhere, a long time ago, *makes his escape personality black.* That the movie star is an ‘escape’ personality indicates one of the irreducible dangers to which the moviegoer is exposed: the danger of surrendering to the corroboration of one’s fantasies as they are thrown back from the screen.”

I found this a very thoughtful and well written response. I’m not entirely sure what that final Baldwin quote means though ‘no one makes his escape personality black’. It made me think about the games I played as a child and the people/characters I pretended to be but I’m assuming that’s wrong because of the context. Sorry just if you have a mo can you elaborate or link me to something?

EDIT: I stand corrected on one point:

In 1948, Superman took on the KKK via the activism of an anti-racist by the name of Kennedy: http://mentalfloss.com/article/23157/how-superman-defeated-ku-klux-klan

I admit I’ve never considered myself a fan of either Superman of Captain America. I liked the recent Cap/Avengers movies and I loved the Superman from the old Justice League cartoon. I don’t think the problem I had was their morals or idealism but how often that was poorly portrayed and the unfortunate implications that stood unchallenged with their version of morality.

With Superman it was a case of bad writing. Too many Superman stories don’t challenge him, they ask him to rely on his physical abilities rather than his brains and moral strength. There are too many Superman stories out there where, despite all of Lex’s money, power and strength, Lex comes off looking like the little guy and Superman like the bully.

With Captain America, well I’d start with the name. He may well represent an ideal of justice to Americans but the way he’s set up as a world protector rings extremely false for the rest of us.

I agree whole heartedly with everything that Robert Jones said. I remember feeling this as a kid, even if I couldn’t put it into words then. It’s why my heroes were Batman, the Ninja Turtles, Loki as he is in the Eddas- people who had to hide from the authorities, people who couldn’t rely on the authorities to support them or do the right thing.

I don’t think this makes the way you read Cap or Supes wrong or irrelevant, but for some of us these guys have never been on our side. And that’s the reason for some of the cheering when they fall, when they’re sullied. You talked about how the heroes we relate to are tied to our age and maturity and I couldn’t agree more. But the older I get the less I see characters like Superman and Captain America as an interesting interpretation of heroism and good. If I was going to point to interesting people who embody those ideas I’d point to Dr Hawa Abdi and Aki Ra.