The X-Men are one of the most unusual success stories in comics history. Initially the black sheep of the original 60’s Marvel offerings (there was a five year period where Uncanny X-Men solely published reprints of older stories), they wouldn’t find success until writer Christopher Claremont took creative control in the summer of 1975. Under Claremont, X-Men transformed into the publisher’s hottest title and multimedia juggernaut in its own right thanks to classics of the superhero comics genre like “The Dark Phoenix Saga” and “Days of Future Past.”

As theaters worldwide prepare for this week’s release of a big budget film adaptation of the latter storyline, it’s an appropriate time as any to think about the X-Men mythos’ defining characteristic: an (often uneasy) metaphor for marginalized people.

At last year’s Fandomfest in Louisville, Kentucky, X-Men co-creator Stan Lee was asked if the way X-Men hosts a variety of diverse characters was intentional and if he considered himself a social advocate. Here’s his response:

I wanted them to be diverse. The whole underlying principle of the X-Men was to try to be an anti-bigotry story to show there’s good in every person.

At the risk of calling bullshit on the godfather of modern comic book storytelling, Lee’s answer is a little shaky. While the X-Men were billed from day one as a group of strange young heroes “sworn to protect a world that hates and fears them,” the early stories under Lee and Jack Kirby were centered around five clean cut white teenagers who attended a private boarding school. Cyclops may have had to wear sunglasses at all times but at least nobody shouted slurs at him on the street. Lee may have intended the X-Men to be an anti-bigotry story but it was one without much bite; although human villains may want to destroy them, regular bystanders treated characters like Cyclops and Jean Grey no different than they would Thor or Iron Man.

And really, why wouldn’t they? Beyond their powers being natural in origin, the X-Men were just another set of costumed superheroes.

After Lee and Kirby left the book, Uncanny X-Men was taken over by a series of creators (including Neal Adams and Arnold Drake) before languishing in relative obscurity. It wasn’t until Marvel relaunched the book in 1975 under Len Wein and Dave Cockrum in a 66-page one-shot, Giant-Sized X-Men #1, that X-Men found what it was missing: something resembling actual diversity.

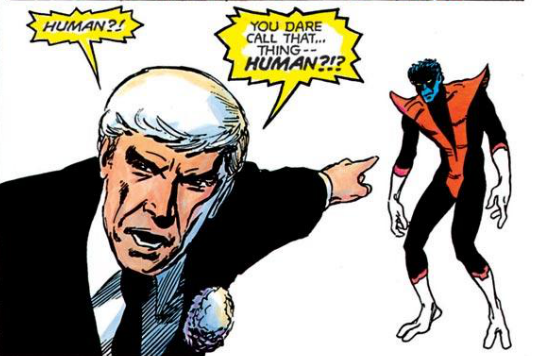

Wein’s all-new “international” team included Japanese mutant Sunfire, Native-American strongman Thunderbird and Storm, a Kenyan weather goddess. Even the ostensibly Caucasian members of the team were physical outcasts; Nightcrawler’s blue fur and demonic appearance frightened people so much a German mob tries to kill him, Wolverine’s strange hairdo and anti-establishment demeanor couldn’t be any further from the preppy, blazer-wearing initial roster of X-Men.

What’s more, the pronounced diversity of the X-Men naturally led to far more interesting stories. Storm and Colossus were thrown out their respective elements into life in a country that was completely alien to them, and Thunderbird openly resented his teammates, dying after refusing to listen to Professor Xavier.

Cut to 1983. By now, Chris Claremont and collaborators like Cockrum and John Byrne have turned Uncanny X-Men into Marvel’s top title. This afforded Claremont the kind of creative freedom to do a story with teeth in the form of an original graphic novel, God Loves, Man Kills.

The book’s opening, in which a black mutant child and his sister are hunted down and executed by a group of “anti-mutant crusaders”, is as shocking today as it was over 30 years ago. Not only does Magneto not show up in time to save them, their killer isn’t a giant robot or disfigured mad scientist but a beautiful Caucasian woman. In God Loves, Man Kills, Claremont gives bigotry a face that’s disarmingly familiar within the everyday lives of readers.

While just as popular (if not more so) in the 1990’s, the X-Men family of books (which by now included Uncanny X-Men, adjectiveless X-Men, Wolverine and a host of other titles) grew stagnant as it drifted away from its core conceit, thanks to stories about clones, time travel, and time traveling clones. It is, however, worth pointing out that this period of time saw the creation of the Legacy Virus, a mutant-targeting plague that kills a number of major characters (including Colossus and his sister) before a cure is developed. It’s hard not to read the virus as an allegory (albeit a clumsy one) for HIV/AIDs and its destructive toll on the African-American and gay communities in North America.

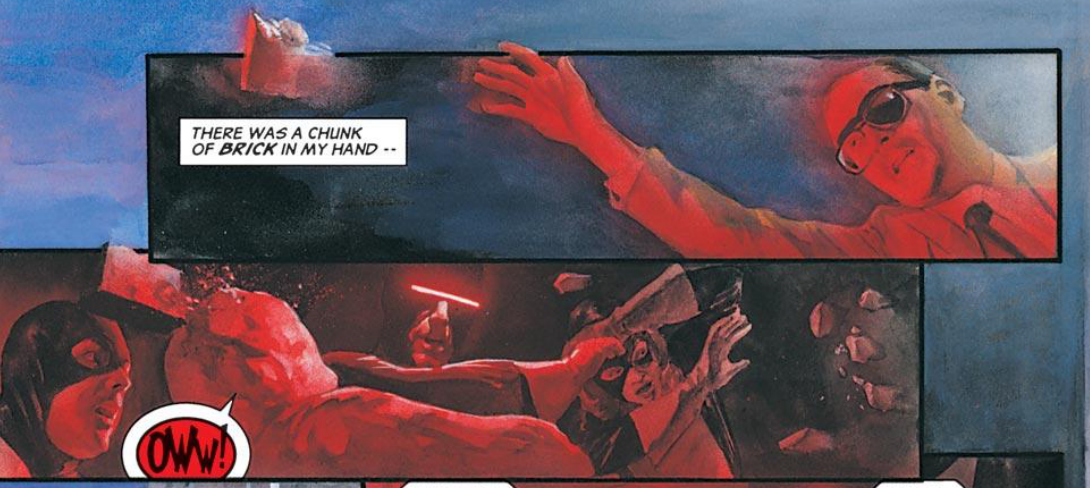

The most important X-Men comic from this period of time isn’t from a X-title at all, but an issue of Marvels, a four issue first person, 40 year tour of Marvel’s history written by Kurt Busiek and painted by Alex Ross. In the mini-series’ second chapter, we’re shown how humanity views mutants through powerless Daily Bugle photographer Phil Sheldon. While Sheldon finds heroes like The Avengers awe-inspiring, he and others are quick to give into racist violence during a chance encounter with the X-Men in the 1960’s.

Surprised by his own actions, Phil matter-of-factly reflects on how he and his fellow humans see mutants.

They were the dark side of the marvels. Where Captain America and Mister Fantastic spoke to us about the greatness within us all — the mutants were death. They didn’t even have to do anything. They were our replacements, the scientists said. The next evolutionary step. We — Homo Sapiens — were obsolete. And they were the future. They were going to kick the dirt unto our graves.

When Phil discovers his daughters have been harboring a young mutant girl named Maggie, he’s forced to reconsider his preconceived notions about mutants while worrying about his own family’s safety. After fleeing a mob swept up in anti-mutant hysteria, Phil runs home to discover that Maggie has left, leaving him and his family a note in crayon thanking them for their kindness. Distraught, Phil is haunted by the knowledge that he will never know whether or not she survives out on her own.

Even though this is a relatively minor portion of Marvels, it’s an incredibly important one. Not only does this story retroactively give us a story about the original X-Men that actually examines the mechanics of racism (sorely missing from the original Lee/Kirby material), Busiek makes a point of showing the reader Phil’s own inherent, everyday bigotry. As Phil Sheldon is intended to act as a reader proxy throughout the story, giving us a ground level view of the often fantastic Marvel Universe, it’s clear that Busiek intended him to be a mirror held up to reader’s own often unconscious prejudices.

When we discuss issues like minority representation in media, it’s important to place a priority on the viewpoints of people who are actually affected by it in their day to day lives. With that in mind, I sought out X-Men fans who are people of color, gay or trans for their take on mutant-as-metaphor. Below is a brief testimonial from Jonathan Massaquoi, a black DC native and lifelong X-Men reader.

I first got into comics during elementary school with a random issue of Cable that was probably not very good, it being the 90s and all. I remember actually reading some of Grant Morrison’s JLA run, particularly “Rock of Ages”, among other stuff. The X-Men naturally became a more constant read thanks to the Fox animated serie,s just like how the animated Batman series did the same for me.

I guess I consider the X-Men appealing in terms of having a host of characters who are feared by a majority for what they are rather than for what they’ve done. The sense that the whole world at times is against them while they try to save it makes for an interesting bit of adversity and a profound contradiction for the characters to face. It’s quite different from what more traditional DC superheroes may experience as Marvel has its characters dealing with people you’re trying to save can distrust or even hate you.

While to be more exact in the general idea of marginalizing a group, the X-Men make for an odd group when it has individual characters with more power than can be found in the entirety of the rest of humanity to a sheer scale found from such characters as Phoenix Jean Grey, Legion, etc.

Of course my knowledge can be quite limited about the metaphors to be found, in what’s an incredibly long run of stories, that handle quite well the topic of minorities being marginalized. There may be a single issue that deals with some of the perceived failures and I would more than welcome it.

Join us for the second part of this piece on Monday where Max looks at queer issues in the X-Men stories of Bryan Singer and Grant Morrison, as well as the future of the X-Men.

One thought on “X-Men and the Other: The History of Marvel’s Mutants as Minority [Part 1 of 2]”

Comments are closed.