X-Men and the Other: The History of Marvel’s Mutants as Minority is a two-part examination of the successes and failures of X-Men as an allegory for real-life minorities. For part one of this article, click here.

The 2000s marked some major changes for X-Men as a concept, some less obvious than others. While previous decades centered around mutants as an allegory for racial discrimination, that took something of a backseat to a new focus: effectively, mutants became queer.

There were seeds for this, of course. Reverend Stryker’s holy crusade against mutants in God Loves, Man Kills is pretty clearly in this vein, for instance. But as gay issues and people became more acceptable discussion points in pop culture, creators were finally able to incorporate these themes in a more meaningful way.

In the summer of 2000, Fox released X-Men, the first film adaptation of a major Marvel comics property. Boasting a (in hindsight, very poorly thought out) tagline of “TRUST A FEW, FEAR THE REST,” Marvel’s favorite mutants were brought together on screen by The Usual Suspects director Bryan Singer and an impressive ensemble cast. Singer directed the sequel, X2, before bowing out of a third movie. He recently returned to direct X-Men: Days of Future Past.

In interviews, Singer has always been forthcoming about the films being an allegory for homosexual identity. In the first X-Men, Singer emphasizes single moments of trauma for characters as the film opens. Magneto as a child in a Nazi concentration camp first manifests his powers while being torn away from his parents, for instance. But the second of these moments, centered on Anna Paquin’s Rogue, is especially notable.

Rogue’s mutation, the ability to painfully absorb the life force of others through physical contact, manifests itself while she’s kissing a boy. Singer deserves a lot of credit for these scene; it’s genuinely horrifying. As Rogue’s would-be partner writhes in pain on the floor, her terrified parents attempt to comfort her but she pushes them away screaming “DON’T TOUCH ME!” Rogue feels she has done something “wrong.” Although this is a fairly chaste sexual encounter between two heterosexual characters, it’s not hard to read Rogue’s self-shame as indicative of denial of a blooming sexual identity. Like many confused gay teenagers, she finds herself forced to live life on the street before meeting Wolverine.

Speaking of, the true star of Singer’s X-Men movies is Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine, a fact that infuriates many comic purists to no end. But what’s interesting is that Singer takes the central concept of Wolverine from the comics, a man with no memory of his past, and tweaks it so that he is a man in search of his own identity. Professor Xavier entices Wolverine to stay with the X-Men under the promise that he will help him find clues to his forgotten past, but he instead finds what he was missing: a community, a family.

(As an aside, it’s interesting that Jackman’s Wolverine is portrayed on screen as a subject of sexual desire, in stark contrast to his cinematic peers like Batman or Spider-Man. With the exception of Mystique, the women of Singer’s X-Men films are fully clothed at all times yet Jackman is often shirtless, sometimes even bare ass naked. This titillation is even consistent in the X-Men films Singer hasn’t directed, such as last year’s The Wolverine.)

The most famous and, fittingly, obvious instance Singer incorporates gay metaphor into his films is the famous “Have you tried not being a mutant?” scene from X2. While the explicit use of familiar clueless anti-gay rhetoric (in the form of Bobby’s well-meaning but bigoted parents) is meant to be funny, Singer does a nice job of showing that not all prejudice is necessarily as maniacally insidious as the kind we see in the film’s villain, Brian Cox’s human supremacist/military scientist take on William Stryker.

If Singer’s X-Men films can be distilled down to a core focus, it’s identity. We especially see this in how the meaning of mutant code names are reimagined for the screen. While “Rogue” and “Mystique” were initially imagined as superhero/supervillain handles, here they act as a signifier of mutant identity. When Magneto asks X-Man in training “Pyro” his name, he responds with “John.” When Magneto presses him further (“What’s your real name, John?”), we understand that, to Magneto at least, the name he chooses for himself is his true name and his old “human” identity is superfluous. Even Xavier’s less radical, attempting-to-live-in-harmony mutant faction subscribe to this on some level. Ororo Munroe would seem to see herself both on human terms as Ororo and, as a mutant, “Storm.” Two distinct halves of a whole.

Hot off the box office success of the first X-Men film, Marvel put Grant Morrison (DC’s JLA, Doom Patrol, The Invisibles) at the head of the creative table for a drastic relaunch that fundamentally changed the property’s status quo. Morrison’s X-Men were reimagined to be less super heroes and more guardians of a new generation of mutants. A number of these changes are directly from Singer’s films: team members wore jackets instead of masks, and Charles Xavier’s School For Gifted Youngsters was once again truly a school (this time with an on-site teaching staff and enormous mutant student body). But in a blog post for The 4th Letter, David Brothers outlines the true innovation of Morrison’s New X-Men:

The X-Men have often been seen as a metaphor for oppressed peoples, with black and gay people being the most common ones cited. Morrison looked at this metaphor, looked at real life, and updated the X-Men to reflect that. Being a mutant became cool in the same way that being black is cool. You can buy clothes and music made by mutants and be down. You can even hang out in Mutant Town after dark to show how open-minded and cool you are.

At the same time, that only goes so far– no one wants to be black, or a mutant, when the things go down or the cops show up. So when Xorn visits Mutant Town and ends up witnessing the death of a young mutant? The humans react the way they always have: with fear and bigotry.

Morrison turned mutants into a subculture, a logical extension of what happens when new elements are introduced into society. They were still oppressed, but they actually had some kind of culture to go along with their oppression. He gave them their own Chinatown, their own Little Italy, and made it a point to show that mutants, while not entirely accepted just yet, were more than just mutant paramilitary teams. There were ugly mutants, ones with useless powers, ones with hideous powers, and ones who just didn’t really care about the X-Men.

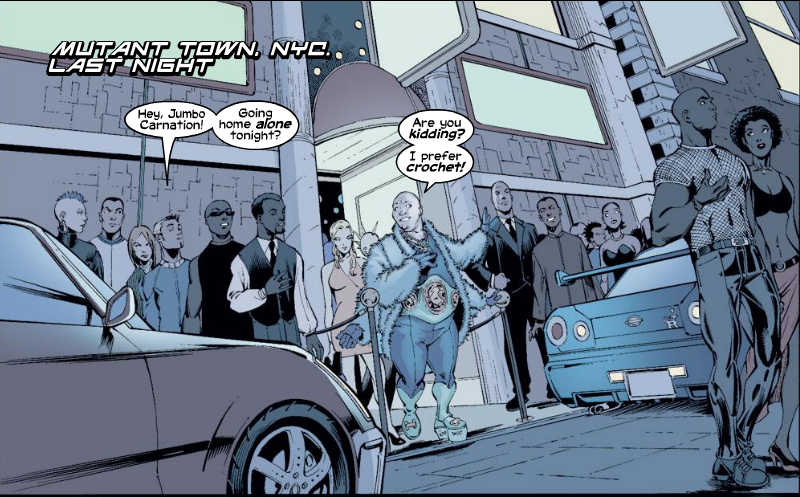

Brothers is primarily talking about race here but this can really be applied to LGBT culture in a broader sense. Finally, mutants had the option of living a real public lifestyle dramatically set apart from humanity. In issue #134, we are introduced to the character of Jumbo Carnation, a (seemingly gay) mutant fashion designer who appears to die at the hands of a human mob (in reality, he overdoses on the mutant power enhancing drug “Kick”).

Morrison frames this in a number of interesting ways. The unnamed character outside the Mutant Town club, possibly a human, soliciting Jumbo, placed against threat of violence he receives on the next page, suggest a culture where being a mutant means living in a contradictory world that hates, fears, and desires them in equal measure. We even see this in one of the New X-Men‘s recurring antagonists, the U-Men, a group of humans who effectively co-opt the mutant lifestyle by killing mutants and grafting their powers onto themselves.

Jumbo’s death, in turn, creates shockwaves through the mutant community and ultimately results in mutant Quentin Quire causing a violent riot at the Xavier School. For the first time, mutants had aspirational figures, leaders who weren’t necessarily out to save the world or rule it.

Morrison’s most overt reference to homosexuality in his run comes when Beast declares to his human female ex-girlfriend that he “might be gay,” he claims as a means of getting back at her. She in turn leaks this news to the press and Beast decides to run with it, partially as a sensationalistic joke and in some sense so that he can inspire alienated young people whether they are mutant or not. In Beast’s mind, the experiences of being gay and being a mutant are functionally identical. While it’s arguable whether this works (you have to wonder if Morrison wanted Beast to actually come out as gay and Marvel wouldn’t let him), it was refreshing to see X-Men stories that confronted these issues head on.

After Morrison’s tenure on X-Men came to a close, Marvel gradually reverted the concept more back in line with its superhero book origins (but notably kept many elements, such as the X-Men as teachers, intact). In the years since the total mutant population has dwindled dramatically, thanks to a convenient magic spell from an out of control Scarlet Witch, and the X-Men now spend far more time fighting supervillains (or each other). In current continuity, Mutant Town is gone, its residents no longer mutants or explicitly dead.

One big indicator of how far the pendulum has swung in the other direction is in an infamous scene from writer Rick Remender’s Uncanny Avengers, a book that follows a “unity team” of both human Avengers and mutant X-Men. The scene in question has mutant team leader Havok declaring that he hates the word “mutant” and would prefer to simply be referred to as “Alex.” Remender received no shortage of criticism for this scene, which many have called tone deaf, and it’s not hard to see why: effectively, this scene has a heroic mutant character advocate for total cultural assimilation.

In this contemporary landscape, where people are quick to declare “racism over” now that there’s a black US President in power, and where heterosexual, white artists like Katy Perry and Macklemore are lauded for “bravely” co-opting racial and sexual identity for entertainment, one wonders if this isn’t a reflection of a society that pushes total assimilation instead of celebrating individuality. Alex isn’t Havok, he’s just Alex. What would Ian McKellan’s Magneto say to that?

Although current X-Men comics seem far less interested in exploring what it means to be “other” than they are in straightforward superheroics, it’s worth pointing out that it remains the place for Marvel to attempt sexual diversity. New gay characters such as students like Anole and Graymalkin, or an alternate universe Wolverine who is involved in a loving homosexual relationship with his reality’s Hercules, show permanent progress in terms of the X-Men as metaphor, even if it’s mostly set dressing.

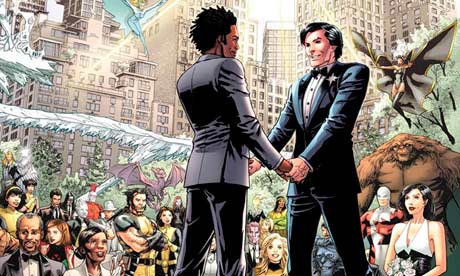

In a highly publicized move, the publicly gay mutant Northstar wed his human boyfriend Kyle Jinadu in an issue of Astonishing X-Men written by writer Marjorie Liu. On one level, this was a pretty transparent sales ploy to capitalize off of many states’ passage of gay marriage laws. But even with that in mind, it’s clear Marvel is aware of a need to cater to a growing reader demographic that is concerned and invested in gay rights issues.

When it comes to X-Men as stand-ins for marginalized people, there aren’t any easy answers. What’s clear is that, conceptually, it has come a very long way from Stan Lee’s initial, superficial metaphor in the 1960s. A major part of why the X-Men appears to have endured as a concept is, fittingly, that it can change and grow over time. Whether that’s as a soapbox for society’s evolving (or loathsome) views on racial or gendered minorities or one unconsidered and yet to come. While the X-Men may never become a completely satisfying allegory, it is often a worthwhile outlet for these issues to be examined in popular culture. The thing about progress, though, is that it can’t be stopped, merely delayed. The future of the X-Men holds real and valuable potential, well beyond Sentinel-ruled dystopian futures and Cyclops’ hypothetical offspring.

As with the first portion of this piece, it’s absolutely essential to consider the viewpoints of the people X-Men is professing to represent. Below is a testimonial from Cheryl Morgan, a trans woman from the UK, a science fiction critic and owner of her own publishing company, Wizard’s Tower.

I became very fond of the X-Men from then on. Knowing that I was a girl, I naturally identified with Jean Grey, though I wasn’t entirely convinced by her choice of boyfriends. When the UK titles folded, I sought out the US originals and stuck with them to the end of the first run. I picked up on the relaunch as well, but the “Dark Phoenix” storyline was too much for me. Jean and I had been friends for 10 years. We grew up together, almost as if she was my big sister, and I suspect that I’ll never forgive Chris Claremont for what he did to her.

I have dipped into what was happening on and off since then, but I’ve never gone back to the series on a regular basis. I’m not sure that any regular series can sustain interest over more than a decade or two anyway. Eventually the fact that the same issues keep getting recycled gets to you.

I am also very fond of the graphic novel, God Loves, Man Kills. It was good to see X-Men tackling real political issues, and the trope of the mutant-hating politician who turns out to be a secret mutant maps perfectly onto the homophobic politician who turns out to be a closet gay. [Editor’s note: In the comic, it’s Stryker’s female assistant who is a closeted mutant.]

The thing about the mutants is that many of them look like perfectly ordinary humans, and yet they all harbor a secret so terrible that they would be rejected by society, possibly even by their parents, if the truth became known. This is a very familiar situation for trans kids, or at least it was back when I was a kid. Hopefully things are much better now.

From my personal point of view, having comics with girl characters in them was very important. I had no sisters, so I had no access to books or comics written for girls. The only female role models I had were in the supposed boys books and comics that I read. The women in most of my comics were adults, so the few girls I saw became important to me. Primarily they were Jean Grey, Barbara Gordon and Supergirl.

One thought on “X-Men and the Other: The History of Marvel’s Mutants as Minority [Part 2 of 2]”

Comments are closed.