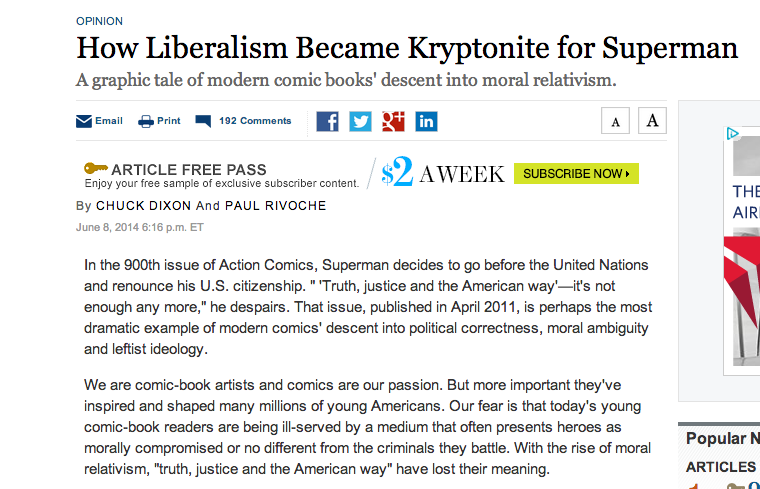

Earlier this week, the Wall Street Journal published an editorial from Chuck Dixon, whose 80-issue run on Detective Comics and nearly 100 issues of Nightwing (just to name a few titles) made up a substantive chunk of DC’s output in the 1990s. Dixon and his co-writer, artist Paul Rivoche, accused contemporary comics of giving way to “moral relativism.”

At Deadshirt, we try not to dip into snark or easy targets. Editorials like “How Liberalism Became Kryptonite for Superman,” however, deserve a rebuttal. Here is ours.

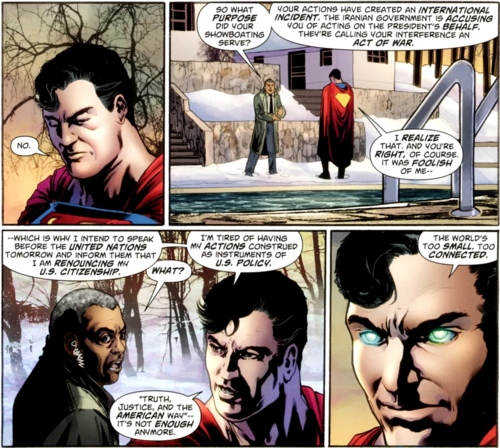

In the 900th issue of Action Comics, Superman decides to go before the United Nations and renounce his U.S. citizenship. “‘Truth, justice and the American way’—it’s not enough any more,” he despairs. That issue, published in April 2011, is perhaps the most dramatic example of modern comics’ descent into political correctness, moral ambiguity and leftist ideology.

This was an enormously weird choice for a starting point. The David Goyer-written backup story Dixon/Rivoche (It’s never totally clear who’s talking at any given time in this editorial, I’m not sure I understand why this was a co-written article. It’s not an especially long piece, certainly.) are referring to, “The Incident,” is three years old at this point and was never addressed again.

I’m also fascinated that, of all possible targets, the writers choose David Goyer, a figure whose politics are pretty debatable. If “the most dramatic example of comics’ descent into leftist ideology” was papered over completely by a company-wide continuity reboot, we’re off to a shaky start.

We are comic-book artists and comics are our passion. But more important they’ve inspired and shaped many millions of young Americans. Our fear is that today’s young comic-book readers are being ill-served by a medium that often presents heroes as morally compromised or no different from the criminals they battle. With the rise of moral relativism, “truth, justice and the American way” have lost their meaning.

We start to see how Dixon/Rivoche are correlating patriotism and morality. This is a bold rhetorical stance to take but rather than explain what that relationship is they just sort of take it as a given. In the story they used as their initial example, Superman renounces his citizenship so that his own political actions as an individual superhero are not seen as indicative of US policy. That seems like a pretty responsible, even ethically applaudable decision on Superman’s part. Whether the authors agree with Superman, certainly he’s doing what he thinks is right here, isn’t he?

What’s frustrating here is that Dixon/Rivoche could have actually made a valid point with the above quote, by citing examples like murderous dictator-for-life Superman in the Injustice comic or even how DC’s branding for the character depicts him with laser death eyes more often than not. That would, however, require some basic research into what DC actually puts out today.

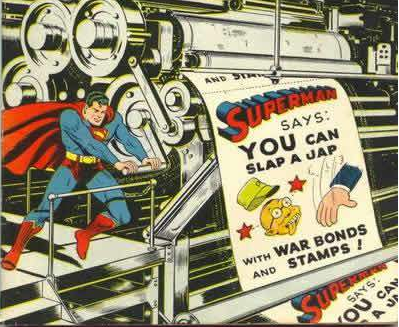

This story commences way back in the 1930s. Superman, as he first appeared in early comics and later on radio and TV, was not only “able to leap tall buildings in a single bound,” he was also good, just and wonderfully American. Superman and other “superheroes” like Batman went out of their way to distinguish themselves from villains like Lex Luthor or the Joker. Superman even battled Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan during World War II.

Superman also led domestic crusades, the most famous against the Ku Klux Klan. A man familiar with the Klan, Stetson Kennedy, approached radio show producers in the mid-1940s with some of the Klan’s secret codes and rituals. The radio producers developed more than 10 anti-Klan episodes, “The Clan of the Fiery Cross,” which aired in June 1946. The radio show’s unmistakable opposition to bigotry sharply reduced respect of young white Americans for the Klan.

The family of one of us, Paul Rivoche, fled Soviet Russia. The fact that Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were themselves immigrants, inspired Paul. Superman was a kind of immigrant, having come to Earth from Krypton, a planet “far far away.” Paul grew up in Canada, but he wanted to depict through his art and illustrations appreciation for both North America and the United States. Similar idealism drew Chuck, the writer in our team, into comics.

Dixon/Rivoche’s rhetorical angle is really confusing. Superman and Batman did occasionally fight Nazi and Japanese agents, but that was more of a focus for their respective film serials (and the Fleischer Superman cartoon) than the actual comics. Why are multiple paragraphs spent discussing Superman’s appearances in other media when this is presumably an editorial about the state of comics? Why is any of this really relevant?

The authors have this incredibly idealized past version of Superman in their heads that suggests they never read any of, say, the Weisinger era stuff where he cruelly tricked his friends and colleagues month after month and generally acted like Old Testament God.

In the 1950s, the great publishers, including DC and what later become Marvel, created the Comics Code Authority, a guild regulator that issued rules such as: “Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal.” The idea behind the CCA, which had a stamp of approval on the cover of all comics, was to protect the industry’s main audience—kids—from story lines that might glorify violent crime, drug use or other illicit behavior.

This is the first out and out misrepresentation of material fact in the editorial. Dixon/Rivoche decline to mention that the CCA was only created after high profile senate hearings that posited that comics were harmful to children and caused juvenile delinquency. Dr. Frederic Wertham’s testimony at these hearings argued that Batman and Robin were in a homosexual relationship, for instance. DC and other publishers adopted these standards out of fear that not doing so would destroy their livelihoods, not out of any moral obligation to society. This is not exactly obscure history by any means.

In the 1970s, our first years in the trade, nobody really altered the superhero formula. The CCA did change its code to allow for “sympathetic depiction of criminal behavior . . . [and] corruption among public officials” but only “as long as it is portrayed as exceptional and the culprit is punished.” In other words, there were still good guys and bad guys. Nobody cared what an artist’s politics were if you could draw or write and hand work in on schedule. Comics were a brotherhood beyond politics.

This is a weird statement considering that the ’70s saw not only the publication of Denny O’Neil/Neal Adam’s highly political Green Arrow/Green Lantern stories, but also saw Stan Lee write a three part Spider-Man story about drug abuse that was released without the CCA’s approval. To say nothing of the explosion of the alternative comics movement and enormously political artists like R. Crumb or Dave Sim. For men who were actually alive during all these things, Dixon and Rivoche have pretty poor memories.

Comics are a brotherhood beyond politics, except in Wall Street Journal editorials that complain that Superman doesn’t call Japanese people slurs anymore.

The 1990s brought a change. The industry weakened and eventually threw out the CCA, and editors began to resist hiring conservative artists. One of us, Chuck, expressed the opinion that a frank story line about AIDS was not right for comics marketed to children. His editors rejected the idea and asked him to apologize to colleagues for even expressing it. Soon enough, Chuck got less work.

Why did the writers skip over the 80’s, the period where DC and Marvel published political, super-popular comics like The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen? To say that this change in attitude came about in the ’90s ignores a pretty important decade for comics as a whole.

I’m not clear on the AIDS story Chuck is referring to here, but Dixon worked off and on for DC until 2008 by his own admission. Is he saying he was discriminated against for over twenty years? That’s a pretty big claim.

The superheroes also changed. Batman became dark and ambiguous, a kind of brooding monster. Superman became less patriotic, culminating in his decision to renounce his citizenship so he wouldn’t be seen as an extension of U.S. foreign policy.

Again, the Batman change Dixon/Rivoche is referring to happened well before the 1990s, in Batman comics from Frank Miller and the writers that followed him. He has to know this, as someone who has written Batman comics extensively. If he had an issue with the tone of these stories, why did he do nothing to change it during his years writing the character?

And, again, why are the authors’ only examples from (at minimum) three years ago? Do they actually read any DC titles at this point? You get the sense that this is a “thinkpiece” written by people who don’t know or care about comics, edited and published by an outlet that doesn’t understand comics at all.

A new code, less explicit but far stronger, replaced the old: a code of political correctness and moral ambiguity. If you disagreed with mostly left-leaning editors, you stayed silent.

Dixon/Rivoche double back to the alleged discrimination, but it still isn’t any more convincing. If any of this is true, why does DC continue to employ outspokenly conservative creators like Ethan Van Sciver and Bill Willingham? I feel like making this personal vendetta a big part of their editorial makes it look like sour grapes from men who have a hard time finding comics work. It deflates the pseudo-objective historical tone of the rest of the piece.

The political-correctness problem stretches beyond traditional comics into graphic novels. These works, despite the genre title, are not all fiction. For years a graphic novel of “A People’s History of American Empire” by Howard Zinn has been taught in U.S. schools. There’s even a cartoon version of “Working” by Studs Terkel. Che Guevara, the Marxist Cuban revolutionary, is the subject of several graphic novels, as is the anarchist Emma Goldman.

I’m not clear on why any of this is being brought up. Dixon and Rivoche aren’t just against superhero comics having a leftist bent, they’re mad that any kind of non-conservative writing exists. Going out in public must be a harrowing experience for these men.

Yet not all comics and graphic novels parrot the progressive line. “Maus” and “Persepolis” have both sold many hundreds of thousands of copies, and are taught in schools. Neither of these two mega-successes can be called left- or right-wing. Pixar’s “The Incredibles” is a parable about the evils of bringing down great people merely because they feature special talents. You can, if you choose to, find libertarian content in “X-Men.” Still, the general message most modern comics send is—in a morally ambiguous world largely created by American empire—head left.

Marjane Satrapi and Art Spiegelman are both outspoken liberals and would, no doubt, very much not appreciate their works being described as non-political. The same goes for The Incredibles, a film that its director Brad Bird has publicly denied having any kind of objectivist bent. Dixon/Rivoche says there’s libertarian content in X-Men but chooses not to cite any actual examples of this. If it can be found, why didn’t they find it? Even they aren’t totally buying this.

This would matter less if comics were fading away. But comics are more popular than ever, as evidenced by Hollywood megahits like “X-Men.” One third of English-as-a-second language teachers in the U.S. use comics. If you doubt the future of this medium, look to Amazon, which bought ComiXology, a company that translates comics to e-books. Or try getting a booth this July at Comic-Con, the mob scene that is the annual comics convention.

Dixon and Rivoche spend much of this essay providing background but never really going further with it. You could argue that readers don’t know about the X-Men movies or San Diego Comic Con except these are the things that always come up in publications like this. This entire editorial feels like it’s written for a young child.

As a peer of ours recently wrote on Comicsbeat.com, when it comes to catching up to the left in modern comics, “Conservatives are taking the remedial course.” As our contribution to that course, the two of us poured years into a graphic novel of “The Forgotten Man,” conservative writer Amity Shlaes’s new history of the Great Depression. But ours is one book. We hope conservatives, free-marketeers and, yes, free-speech liberals will join us. It’s time to take back comics.

What an abrupt ending. Who are comics being taken back from here in that call to action, if not liberals? Gays and racial minorities? Women? Was this whole thing just a giant ad for some comics adaptation they’re working on? The conclusion really embodies what’s wrong with this entire editorial: rather than make one cogent point, the writers vaguely imply some (rather inflammatory) things, but never out and out say it. You get the sense that they know what they want to say but are afraid to say it. If you’re writing an editorial that pulls punches with its points, you’re writing a poor editorial.

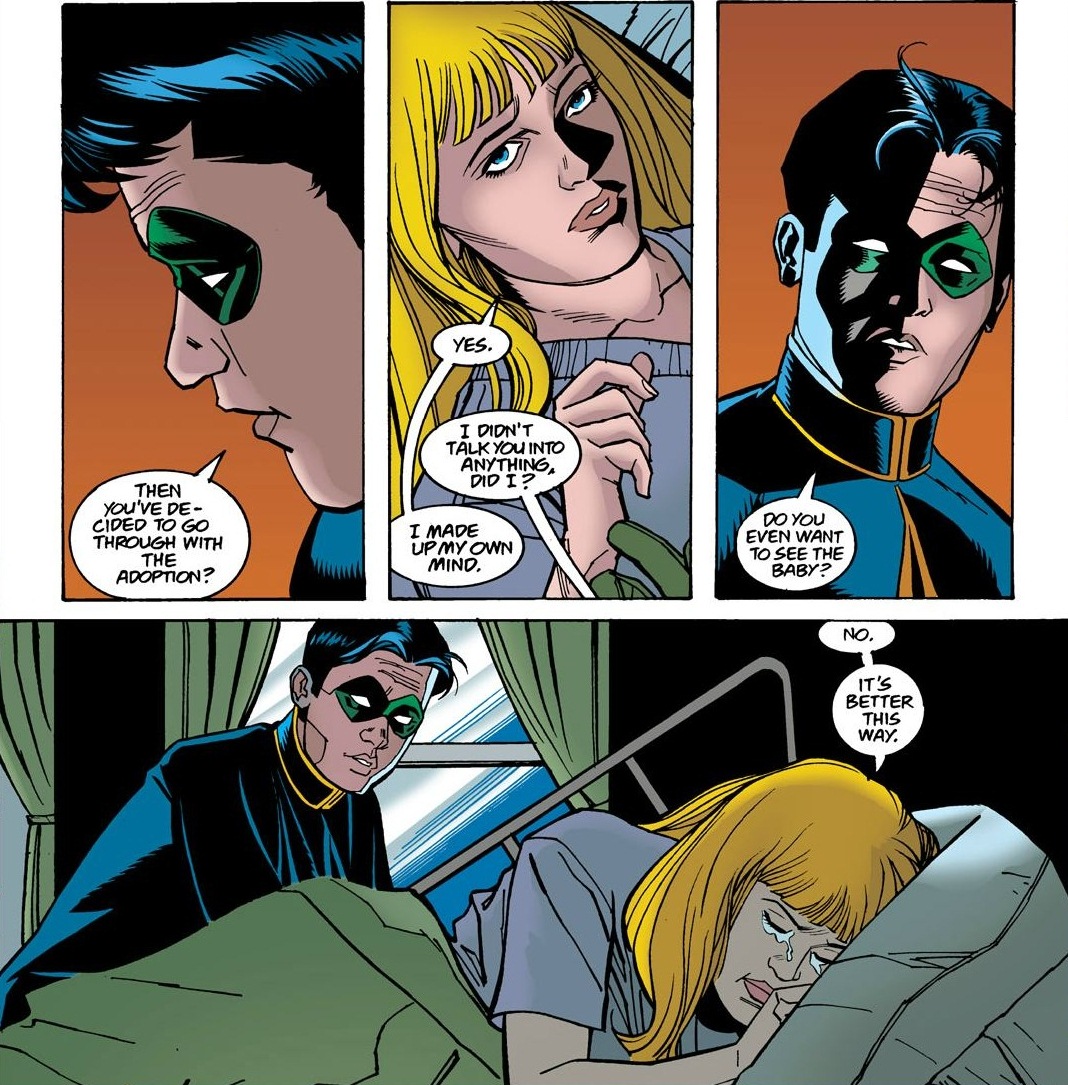

What is the ultimate message of this editorial? That comics don’t take moral stances anymore? But if that’s true, why does Dixon have a problem with superhero comics discussing AIDS? If that isn’t an appropriate issue, why does Dixon’s own work tackle, for instance, the out of wedlock teen pregnancy of crimefighter Stephanie Brown? Or was that acceptable because it involved a woman being punished for having premarital sex? If it’s a good thing that Superman opposes hate groups like the KKK, why is it bad for him to take similar stances today?

From Robin #65. Art by William Rosado. (Source)

Lets call this what it is: men like Chuck Dixon and Paul Rivoche are mad that they are becoming irrelevant in a format that is blossoming. In a comics market place where a book like Sex Criminals sells out multiple printings, it’s clear there is a palpable demand for stories, even light fare like superhero comics, that discuss topics like sex and question authority. If there’s a problem with comics, it’s that they aren’t doing ENOUGH of that. It’s telling that at no point in this article are Marvel and DC taken to task for the rising levels of violence in their stories or their lack of any kind of meaningful outreach to young readers. The only problem is undefined “liberalism.” And if Dixon and Rivoche (and people who subscribe to viewpoints like theirs) can’t adequately explain their moral issues with the state of comics today without the fear of being seen as ignorant, perhaps they should put away the persecution complexes and sit down.

Given the shameful foreign policy decisions made by the current administration, Superman renouncing his citizenship so as not to represent this America was moral and necessary for him to remain a hero. I don’t see Dixon’s problem.

Respectfully, I think the point was missed. Superman is not renouncing his citizenship as a result of any one administration – it is not political. In fact, he he doing this to be non-political. This is a fascinating piece to use as a conversation starter in a social studies classroom – it mirrors another storyline – Superman: Red Son. More than just acting in US self-interest – the story also has me thinking that Superman stands in for the US in general. He is the most powerful force in the world (US military) and is more than capable of fighting all the super villains (Hussein, etc). Yet – he feels he is not doing enough to hlep humanity in general with some of the more “mundane” spectres of hunger and thirst. Great writing.