David Lebovitz gives you a crash course in film from an esoteric genre, director, or foreign country’s cinema, complete with spoiler-free descriptions and analyses of films that act as a good starting point for your own celluloid journey. This edition, he presents you with a look at one of cinema’s first superstars, Charlie Chaplin.

(Source)

In many ways, Charlie Chaplin invented cinema as we know it.

Even if you’ve never seen a Chaplin film in your life, you’ve seen gags popularized and perfected in his films for decades. Many of Chaplin’s earlier films have not aged well, in part because they are so familiar. You’ve seen the same slapstick humor–often the exact same jokes–used in Looney Toons, Mickey Mouse, nearly every cartoon made during and since World War II, countless movies (especially children’s movies) and TV shows. He essentially took classic vaudeville routines, made them his own, and put them on film for the masses.

Originally an employee at Keystone Films, Chaplin became more popular and famous than any other employee at the company, including Keystone founder Mack Sennett. In 1919, Chaplin founded (along with early Hollywood megastars Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and DW Griffith) United Artists, and gathered complete control over his own films.

During the prime of his career, Chaplin had an unprecedented amount of power over his projects. He wrote, directed, produced, starred in, and occasionally scored his own films. (Somewhere James Franco is feeling humbled.) He was one of the wealthiest men in Hollywood, and was world famous during his lifetime for his contributions to cinema and comedy. Chaplin stubbornly refused to make talkies for many years, even after they became the dominant form of filmmaking, and made some of his best silent material while the rest of the world was using audio.

Chaplin’s most famous character, and arguably his only character, is The Tramp.

(Source)

A hapless, good-hearted vagrant, the Tramp is a perpetually polite romantic who dreams of a better existence but doesn’t argue too much with his lot in life. He is often seen wearing baggy clothes, a bowler hat, and carrying a flexible cane. While there was no continuity between any of his films, the Tramp remained thematically the same character across several films.

Though overtly slapstick comedies, Chaplin’s films contained a lot of sociopolitical commentary. They were often critical of capitalism, showing workers toiling away while the rich lounged in the offices and mansions. Many stories were “man against the establishment” stories. At his core, however, Chaplin was an optimist and showed the best of humanity and supported the idea of the American Dream.

For the sake of disclosure, in high school I dressed as Charlie Chaplin for Halloween one year. Most people liked it. (A small-but-embarrassing number of people thought that someone with the last name “Lebovitz” was dressed as Hitler.) I’m still particularly proud of it.

Below are four of the less controversial/more accessible Charlie Chaplin films with which to begin your semi-silent journey. Note that several of these films are public domain and can be found online for free.

City Lights (1931)

(Source)

Often listed as Chaplin’s best film, City Lights proved that Chaplin didn’t need audio to pull at an audience’s heartstrings. It can perhaps best be described as a romantic dramedy. It features slapstick humor (including a boxing scene that ranks amongst my personal favorite Chaplin bits), solid drama, and some truly touching romantic moments.

The Tramp meets and instantly falls in love with a blind flower girl. Shortly after buying a flower, a luxury car drives away, which leads the flower girl to believe that the Tramp has departed and is actually a wealthy man. Later that night, the Tramp stops a drunken millionaire from committing suicide. The millionaire rewards the Tramp and becomes his friend and benefactor. However, each time the millionaire sobers up, he has no memory of the Tramp. The Tramp later finds out that the Flower Girl is going to be evicted from her apartment, and that a European doctor has come up with an operation that cures blindness. Between his friendliness with the drunken millionaire and odd jobs–including the aforementioned boxing match–the Tramp tries to find a way to raise the money for the girl he loves.

City Lights is a comically beautiful film that in many ways is the essential Tramp story. He is a bumbling man who is often the victim of circumstance, but at his core he is selfless and will do anything to help people he loves. City Lights is beautifully shot, tightly scripted, well acted by all parties involved, and is once of Chaplin’s most dense silent films.

The Gold Rush (1925)

(Source)

By far the least complicated film on this list, The Gold Rush takes the Tramp out of his typical city environment and places him in a small mining town where he looks for gold and finds love.

The film sees the Tramp travelling to the Yukon to participate in the Klondike gold rush. Along the way, he gets stranded in a remote cabin with burly prospectors. The Tramp later falls in love with Georgia, a saloon girl, after mistakenly believing that she is in love with him, and attempts to court her. Notable scenes include the Tramp making rolls dance, being forced to eat a shoe and devouring it like it were spaghetti, and the cabin teetering on the edge of a cliff.

In 1942, Chaplin re-released the film with some changes, most notably the inclusion of auditory narration recorded by Chaplin himself. He also tightened up a few scenes, added a score, and changed the film’s speed so it would be more accommodating to the audio. The original film has fallen into the public domain, but the re-release, which is preserved far better than the original, is still under copyright.

Modern Times (1936)

(Source)

Modern Times was Chaplin’s take on industrialization and how it was affecting the average worker. The film’s scenes in the factory, including the Tramp getting pulled through gears, rank among Chaplin’s most famous, and has some biting commentary that is still relevant today.

In Modern Times the Tramp works in an overly efficient factory, where employees mostly make sure the machines are running well and occasionally act as guinea pigs for projects. The Tramp does his best to keep up with the demands of the assembly line, but eventually has a nervous breakdown and is hospitalized. When he leaves the hospital, he becomes mistaken for a communist and gets in trouble with the law. He and his companion Gamin (Paulette Goddard) do their best to maintain their sense of individuality while on the run from the law in an industrial world.

Modern Times is not true silent film: there are brief moments of auditory speech, and the film features a multitude of sound effects. This, however, may be the most subversive aspect of the film. By using notable audio tropes, Chaplin is rebelling against it by revealing it as overly-efficient cliché.

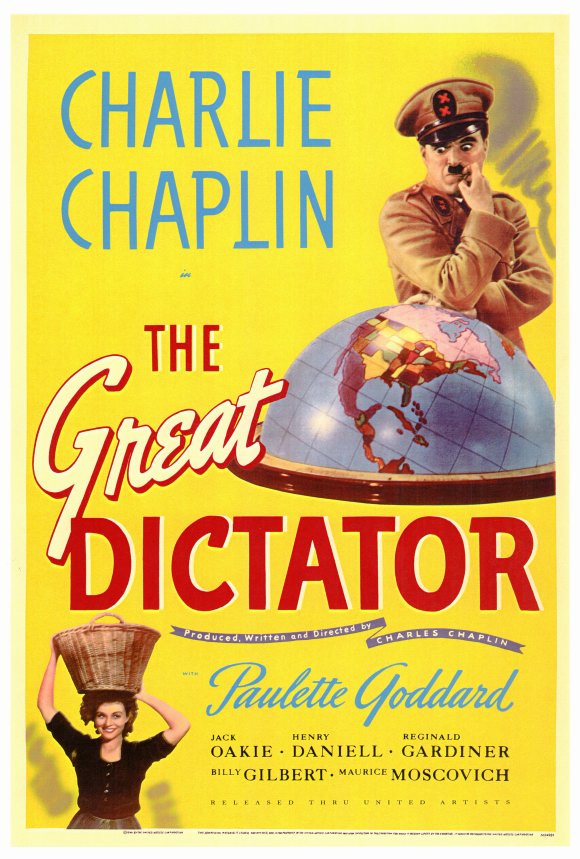

The Great Dictator (1940)

(Source)

The Great Dictator is easily Chaplin’s most political film, and one of his few talkies. In it, Chaplin plays two roles as both the titular dictator and a Jewish barber. While the barber is decidedly not the Tramp, it’s hard not to notice certain parallels between the two characters. Both are hapless, good-hearted, working class romantics who find themselves dragged into situations beyond their control. The similarity between the Tramp’s moustache and Hitler’s was widely noted, which, along with other similarities in their early lives, was one of the reasons Chaplin decided to make the film.

The Great Dictator follows two parallel stories: Dictator Hynkel’s rise to power in a small European country that was on the losing side of World War I, and a poor Jewish barber (who has an uncanny physical resemblance to Hynkel) trying to make ends meet whilst facing persecution from the government. Hynkel has plans for world domination, and uses the Jewish people as a scapegoat for his country’s failures, while the barber remains angry at the injustice but hopeful underneath it all. The barber eventually falls in love with a washwoman, but he gets involved in a larger scheme when mistaken for the dictator himself.

The Great Dictator predated America’s involvement in World War II by over a full calendar year, and at a time before many Western countries knew about the extent or even existence of the Holocaust or Hitler’s other atrocities. It was also the first feature-length film to parody Hitler. Though it does not fit the mold of many Chaplin films–it’s often more dramatic than his previous films, and far more grand in terms of set size and narrative scope–The Great Dictator‘s excellent acting, solid storyline, and historical significance make it a notable and solid film to this day.

Check out more introductions to film genres and filmmakers from David Lebovitz.