Emily Carroll’s new collection of short stories is bookended by a prologue and epilogue starring the author’s young self. The prologue questions: what is beyond the nightlight that the young Carroll reads books by? What if there are monsters waiting just at the edge of the dark?

“What if?” is key to this book of otherworldly terrors. The world of Through the Woods is of fairytale, of olden times when the dark was more unknown and more fearful, full of spirits and danger. The characters often know when danger approaches, but they are marked by powerlessness. Carroll’s protagonists go knowingly into danger, because they have no choice, or they find danger, incidentally, then have no power to ever escape it. They begin fragile, and their stories are marked by an understanding of their vulnerability. By being smart and prepared they do not avoid their fate but delay it. Though the fear of death is more immediate and terrible in Carroll’s world, it is the same as in ours–that death is inevitable, but you may have some effect on how and when. So, like the young author, afraid of the darkness beyond her nightlight: by filling the darkness with terrors, instead of assuming safety, you acknowledge your mortality, and you prepare to struggle for your life.

Carroll is well known for her webcomics, including her breakthrough story “His Face All Red” which is included in Through the Woods, reformatted for print. The success of her webcomics is in part due to her unique use of the web medium to control pacing and suspense. However, limited to left-right, down and across, and without unlimited space to stretch the gutters between panels, Carroll is not at all deterred from creating uniquely disquieting chills.

While online, Carroll’s work can stretch through blackness, Through the Woods is packed from edge to edge (as not to waste any of the glossy full-bleed pages). While this does makes the pace of the stories feel rushed compared to Carroll’s online work, she makes up for it by packing the spaces with ambiance and extra pauses where they are needed. The passing of time is an important feature of Carroll’s stories, in the cyclical rhythms of folktales where each night that passes is a step further down into a dungeon. For dead things are patient, but inevitable, and the suspense builds with every moment that the characters languish in wait.

Bordered panels sprawl directionally across full bleed scenes or landscapes, and single panels fill full bleed pages to create a full stop in the action. Where in a browser Carroll creates deep, downward motion, on the page she creates twisting, winding motion that snakes across page spreads.

A panel in “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” sprawls diagonally across a two-page spread, utilizing the top-left to bottom-right momentum of reading.

Carroll has a particular understanding of color that is beautifully showcased in the gorgeous print quality of the book. Each story is visually distinct, with a different palette and treatment of light that builds a unique landscape to set the story. In “Our Neighbor’s House”, stark black opposes stark white, to show the cold of a snow-covered plain, the steam of breath as heat escapes the body, the deep silent night empty of all presence. With a pallet limited almost entirely to five bold tones, or a mix thereof, “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” is dazzlingly bright and crisp. Inside the dread mansion of the lady’s marital imprisonment is nothing but cold, cold blue. She is a stark spot of warmth, in her remaining yellow and red, until she is left cold, blue in her skin and the very color sapped out of her dress.

“My friend Janna” is full of shadows and earthy grays. The air is damp and misty just as the ghost that haunts Janna is cold, ethereal, and uncertain. “The Nesting Place” signifies character more than place with color. In contrast with the heroine Bell’s grey solidity and gloominess, Rebecca, unfamiliar in-law, is bright and ethereal in her happy beauty, with pastels never used elsewhere, and white lines that define her skin instead of the black used for all of the other characters. But throughout all the stories, red is always the color of horror, from the blood red moon, the song of a dead woman, his face (all red), the coursing blood of a spirit, and worms that nest into your skin and steal your life. The visual focus of red to signify terror is simple and chillingly effective.

Separate from these new stories, the reformatted “His Face All Red” seems a somewhat odd inclusion in the book. Thematically, it is a solitary story of men in a book of stories about women. The lead is haunted by his own cowardice and jealous violence, not acting against a fate over which he has no control. Furthermore, though Carroll’s artwork and coloring in “His Face All Red” are high caliber as always, four years have passed since its making, and the artwork of the other stories shows four years of finesse in linework, color handling, and depiction of light. Compared directly to these new stories, “His Face All Red” looks muddy and dim in a way that doesn’t do the story justice. Where sparse moments of red-splashed horror would pop backlit off the screen, here they seem so much less impactful in comparison to the crisp swaths of bloody red that punctuate the rest of the book. While “His Face All Red” is nicely reformatted for the book, lettering rewritten and enlarged for the format, it was not written to be read winding back and forth. The story loses some of its suspenseful fervor without the directional downward scroll of the web browser creating a sense of descent that builds until the lead himself climbs down, down into the deep dark pit at the culmination of the story. The full horror of “His Face All Red” depends on Carroll’s ability within the medium to thin the story’s pace down until it proceeds, single panel by single panel, through the deep darkness of a browser window.

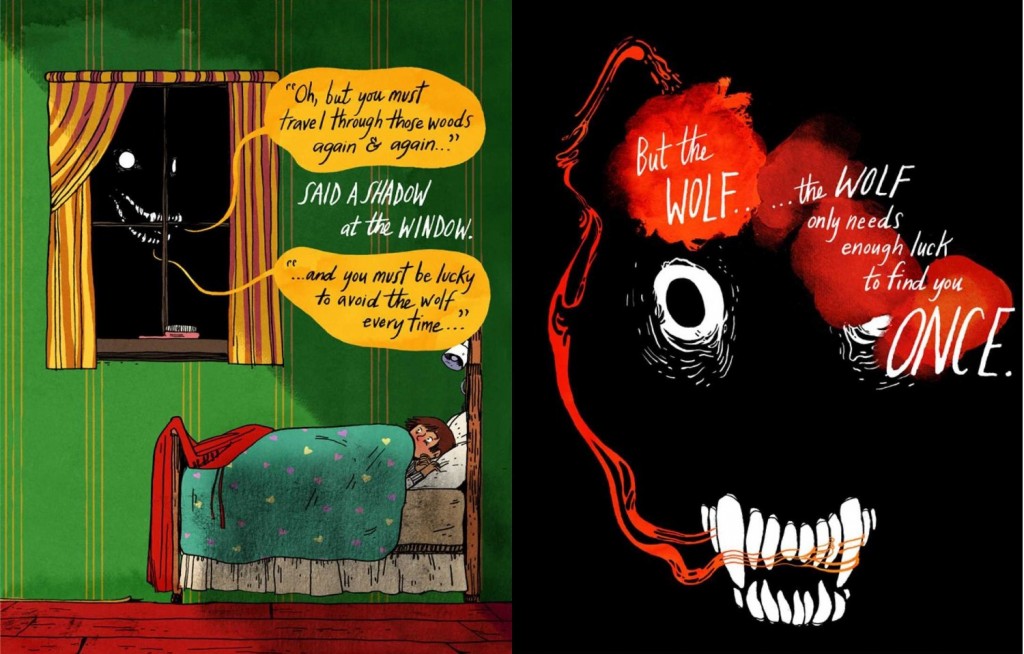

In the conclusion of the book, as in the prologue, Carroll brings the stories into our own age by writing about her young self, here as a Red Riding Hood stand-in. The twist on the classic fairytale is neatly tethered to her personal, modern experience, as the young girl travels not away from home to her grandmother’s house, but between the homes of her father and mother. In this version, she does not stray from the path or meet the wolf, but takes a cheerful evening walk, safely traversing a beautiful forest full of colorful sights. She goes to bed happily, with a thought “I knew the wolf wouldn’t find me!”

But the wolf offers some wisdom:

We are fragile things, and mortal, so we must prepare for what waits for us in the dark.

Through the Woods is available now from McElderry Books.