In The Rundown, Deadshirt dives into our cardboard long boxes to shine a light on important, unusual or otherwise remarkable comic runs from a specific creative team.

The Series

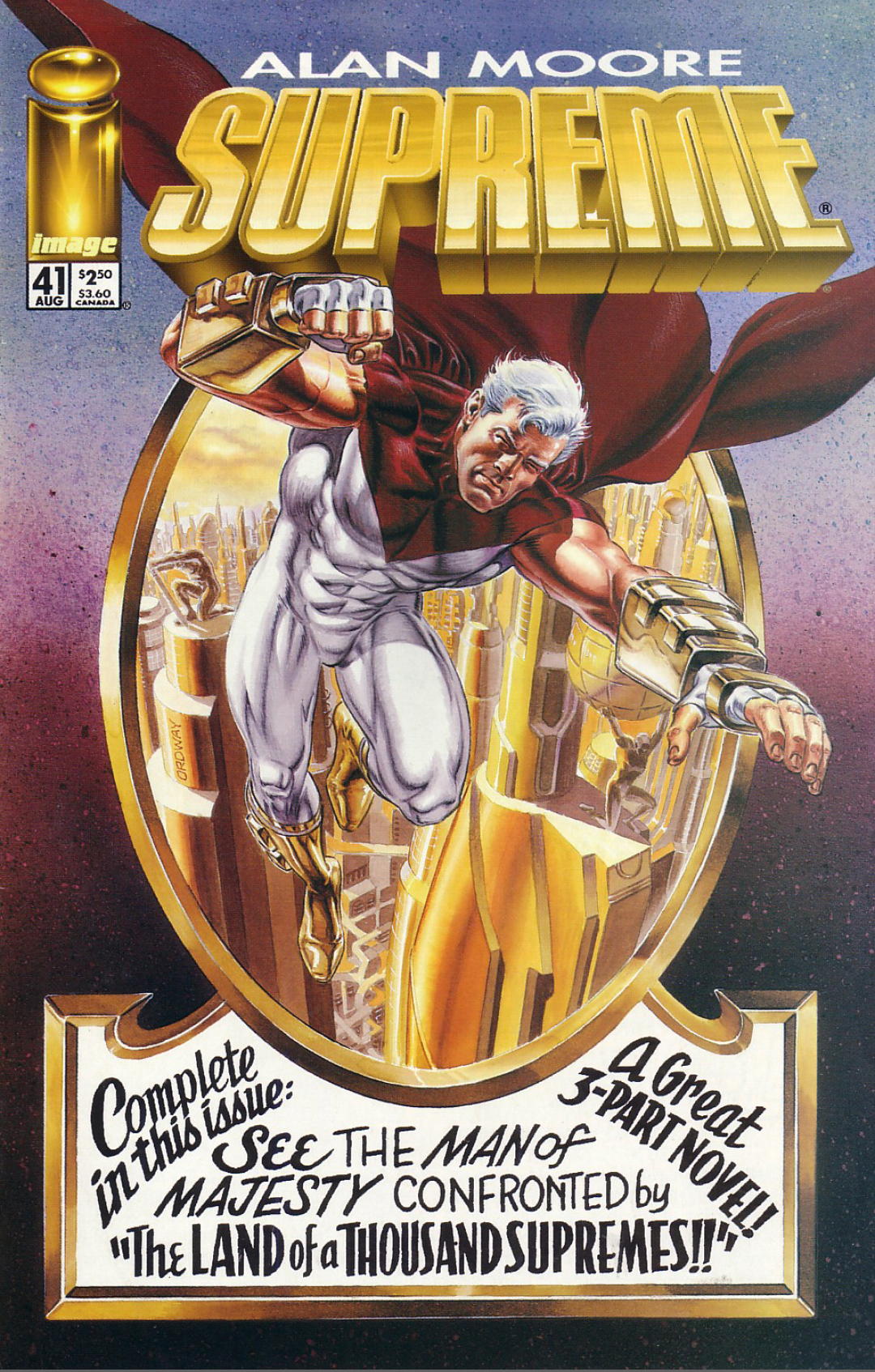

Supreme and Supreme: The Return (1996-2000)

Supreme Issues 41-57

Supreme: The Return 1-5

Written by Alan Moore

Art by Joe Bennett, Rick Veitch, Chris Sprouse, Jim Starlin and more

Image Comics / Maximum Press / Awesome Entertainment

At A Glance

Before Brandon Graham was spinning Moebius-influenced yarns covering old Bobby Liefeld castaways with Prophet, Alan Moore was the God King of Image Comics Recreational Subversion. No stranger to taking on weird projects in the 90s post-speculator boom, perhaps Moore’s finest work slumming it with Liefeld, Jim Lee and company is his tenure with Supreme, Liefeld’s blatant Superman stand-in. Presaging the lovingly pulp touch of his later America’s Best Comics line, Moore’s twenty-two issue run on Supreme, through its publisher shifts, lengthy shipping delays, and artist replacements, reads like one long love letter to the Last Son of Krypton, and remains some of his most underrated cape comics.

Throwing out everything that came before it, Moore rebuilt Supreme’s fictional existence from the ground up, metatextually explaining away the retconning utilizing one central conceit that gives the entire run a sense of majestic honesty, leading to a superhero story that examines the roots of all superhero stories without shame, cynicism, or malice. You know, sort of the opposite of what Moore typically does. The run is broken into three distinct arcs, the main thrust of which is “The Story of The Year,” the first and easily best act. Following in the footsteps of Moore’s own untouchable “Whatever Happened To The Man of Tomorrow?” Supreme functions as a charming, nostalgic throwback to a bygone era of Superman stories built on a genuine sense of adventure. That the book is crafted by a man so regularly disdainful of the genre that made him a household name compounds how special a series it remains.

Standout Issues

Supreme #41

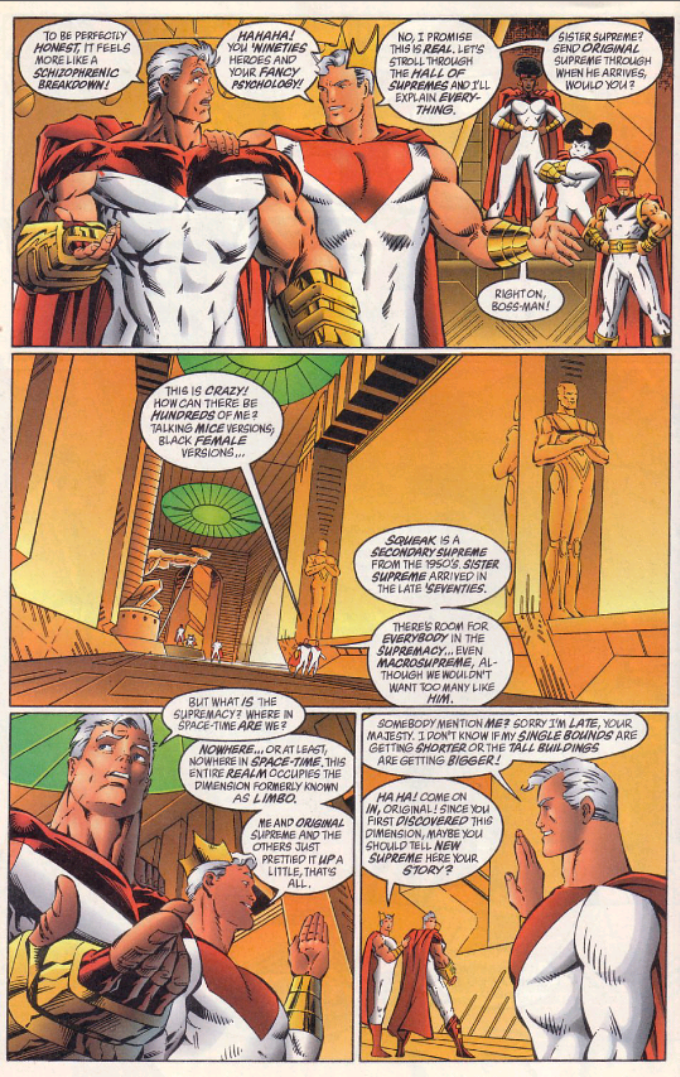

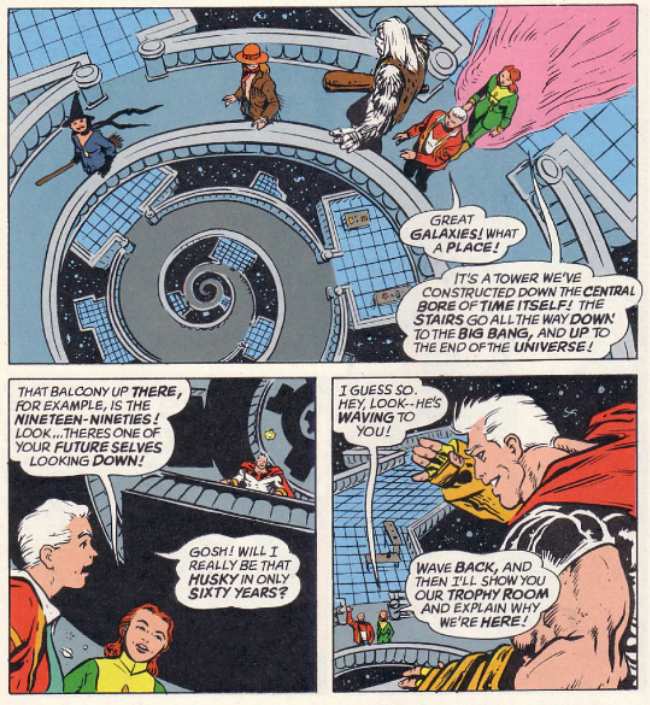

Moore’s run opens with this standout issue aptly dedicated to legendary Superman artist Curt Swan. In it, our titular hero is introduced to The Supremacy, a sort of Valhalla for the various iterations of Supreme. This is where they go after obsolescence sets in and a wave of retroactive continuity births a new Supreme to carry the mythological torch into a new era. Typically, Supreme discovers, Supremes never get to visit this realm until they’ve been “cancelled,” but he is unique, and so learns all of this from his predecessors before the Revision Wave hits, making him the first self-aware Supreme, a distinction that lends a decidedly 90s, Gen X-y tint of angst to our hero’s otherwise Golden Age demeanor.

Here, Moore establishes a new status quo for Supreme, whose Ethan Crane alter ego is revealed in this iteration to be a comic book artist working on a superhero title styled after Supreme himself: Omniman. His “Lois Lane” is also introduced, a fellow creator at Dazzle Comics named Diane Dane, who writes their Warrior Woman series. Yeah, the self-referential layer cake of meta stacks pretty high in this one, but the frosting is so fucking sweet, you hardly bat an eye.

A structure that apes the 3-part paradigm of old superhero tales is utilized as further evidence of a throwback mentality, setting the pace for many future issues as well. Bennett’s ability to homage various eras of Superman (and falsified Supreme) history shows a range that the artist wouldn’t flex as fully for some years, but his natural penciling style at the time grounded Moore’s flashback feel in a very Image aesthetic.

Supreme #42

The next issue in the run introduces the first of many Rick Veitch-drawn flashback sequences, a narrative device that models itself on Silver Age back-up stories, but helps to fill in the gaps of this newly created Supreme continuity, both to the readers and Supreme himself. We’re treated to Ethan Crane revisiting his hometown, the Smallville facsimile Littlehaven, a trip that opens the door to a retelling of Supreme’s new origin and an adventure as Kid Supreme featuring a team-up with “The League of Infinity,” a cadre of teen heroes from across history. Seriously, if there was a drinking game that required you to take a shot every time something from Superman mythology was referenced or recontexualized in this comic, you’d be fucking dead, and no retcon could bring you back from the grave.

At first glance, this issue, switching back and forth between Bennett’s modern day art and Veitch’s deceptively simple line work redux of the Silver Age, feels a little perfunctory, but the loving hand Moore seems to be using here is a welcome one, offering a mix of wonder from the past and trepidation for the future that generates some palpable tension. This issue, which formally introduces Darius Dax, a Lex Luthor clone, ends up being incredibly important for the circular paradox storytelling of the opening arc’s grand climax.

Supreme #50

Guest penciller Chris Sprouse (who later became the regular artist) handles the present day aspects of this issue, a densely meta slice of life issue about Ethan Crane collaborating with new Omniman writer Diane Dane. Sprouse’s art is probably who’s you picture when you imagine Supreme; his lean, streamlined style feels like Curt Swan transplanted to the mid 1990s. That he wasn’t the artist behind this entire run is nearly as tragic as Frank Quitely not doing all of New X-Men.

Veitch returns for a series of flashbacks sending up the Mort Weisinger Superman’s hang-ups about relationships and commitment, as Crane reminisces on the history of Supreme’s love life to inspire new ideas for Omniman. These conversations with Diane lead to the heavy subtext of the sexual tension between the two co-workers. Whether or not Diane knows Ethan is really Supreme, the reader and Ethan himself know, so as she lends a critical eye towards the duplicitous nature of secret identities in the context of dating, we feel the sting, knowing our hero can’t in good conscience consummate their unrequited attraction.

The interplay between our reading of Supreme’s fictional life and Omniman’s fictional life and the varying degrees of reality causing comic book coitus interruptus is a serious balancing act of deconstruction, one Moore handles without diminishing the source material or the story at hand. It feels like a smart, sharp take on superheroes rather than a grim tear down.

The Bottom Line

Despite being a little bloated at times and bending over backwards to feel like high-priced fan fiction, Moore’s Supreme run is exciting comics. The metafictional acrobatics jump out at first, but what stays with you is the emotion and heart, the tenderness with which Supreme and his supporting cast are treated by Moore. There’s a maturity on display that elevates these particular cape comics from being mere “adolescent power fantasies” that proves Alan Moore and archrival Grant Morrison aren’t so different after all. They may hate each other, but they both love Superman something fierce.

Whereas Morrison put much of that love into All-Star, Moore takes whatever was left after penning “For The Man Who Has Everything” and uses it to breathe new life into a Robert Liefeld creation that no one before or since (Sorry, Erik Larsen) has managed to make feel vital and fresh. Yes, he does this by turning him into Superman, essentially, but he’s able to explore themes and ideas DC seldom lets anyone tackle with Big Blue. From showing Supreme’s difficulty with understanding the moral implications of resurrecting his dead girlfriend as a robot (in Supreme #54’s “The Ballad of Judy Jordan”) to showing the feral, violent side of Krypto stand-in Radar (In Supreme: The Return #1), Moore injects enough new ideas into his Superman pastiche for it to evolve into its own curiously infectious beast.

The later issues, after the initial arc ends and the shipping hopscotch begins, lack some of that initial magic, but remain enjoyable romps with unexpected twists on typical superhero tropes, further evidence that Alan Moore is capable of deconstructing superheroes without the vitriol he seems to be so known for now.

Additional Reading

– All of Moore’s ABC line would be great further reading material, but Tom Strong, reteaming with Supreme artist Chris Sprouse is cut from the same cloth as this run, fun, smart pulp stories that resonate far more fully than they should.

– As far as Superman pastiche goes, you could do worse than read Paul Jenkins and Jae Lee’s original mini-series of The Sentry for Marvel, or The Age of The Sentry, featuring work from Jeff Parker, Paul Tobin, and others. Each presents a different extreme, but both are rewarding. Ignore pretty much anything else Sentry related.

– Fellow bearded Brit Warren Ellis is launching a new take on the mythos with Supreme: Blue Rose today, featuring art by Tula Lotay. Should be interesting to see what direction Ellis takes.

Check out other installments of The Rundown!

2 thoughts on “The Rundown: Alan Moore’s Supreme Is the King of Superman Pastiche”

Comments are closed.