Diversity and representation have long been a serious issue in the film industry, and 12 Years A Slave winning some Oscars hasn’t exactly changed that. Outside of that prestigious anomaly, people rarely imagine black film to be much more than gangster movies, cookout comedies, and Tyler Perry. Our very own Dominic Griffin will prove otherwise, shedding a light on unsung, underrated, forgotten and new films that show the breadth and versatility of the black voice in film. Named after one of Billy Dee Williams’ affectionate nicknames, this is Dark Gable Presents…

A few years ago, I read an interview with the guy from Plain White T’s (I’m not googling his name and you can’t make me) about their song “Hey There Delilah.” The gist of the piece was that this dude wrote this hugely successful pop song about a girl he was into and then the real life Delilah still wouldn’t fuck him. The presumptuous tenor from both the singer and the interviewer had a conspiratorial tone that was pretty discomfiting, half suggesting the article would end with the line “Not even a beej?”

Alas, this is a pretty commonplace narrative in pop culture, the tortured young artist and the girl who won’t recognize his Earth-shattering genius/obvious coiled sexual power. The male in these scenarios is very often a wiry white dude, glasses optional, and the female is almost always some variation on the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, glasses mandatory. We’ve all seen this exact fucking story play out cluelessly time and again: a pathetic and frustrating tale of beta male idiocy crafted by the beta male in question, either as the filmmaker or songwriter, with little to no distance from the romantic loss itself and even less time/energy/consideration reserved for the woman of the tale. For once, it’d be nice to see this story from the other side, or at least made by an artist removed enough from the inciting event to have gained some perspective on the whole thing.

This is why our film this week is the somewhat pretentiously titled An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, the experimental, genre and medium traversing debut of artist/musician/filmmaker Terence Nance.

While making lists of films for this column, I was struck by a sad disparity. If I’m in the mood for a very specific kind of film, I can usually find something on Netflix or Hulu to watch. Such is the vastness of the Internet. If I want to watch those search results dwindle to a crawl, all I have to do is add “black.” I can probably find ten movies like Garden State with one eye closed, but if I wanted a similarly quirky tale of youthful navel gazing for a more colorful cast, it’s a bit more difficult. That’s kind of how I discovered this film. I saw the trailer last year and thought “Oh, cool. A blipster version of Eternal Sunshine!” to myself. Thankfully, An Oversimplification is so much more that that.

The premise of the Nance’s film is simple enough, but the execution is dizzyingly labyrinthine. The core of the work is a short film Nance made a few years earlier entitled How Would You Feel?, about a man (Nance himself) being stood up for a date. Taking that particular moment of disappointment, the short film cuts back and forth throughout the lead-up to this outcome, filling in emotions, plot details, and other inferences with the use of omniscient, sympathetic voice over narration from Nance and Reg E. Cathey (the future Dr. Storm in the upcoming Fantastic Four film). We come to realize Nance and the girl who stands him up have a strange relationship. It becomes clear that she is “taken” and that his love for her is unrequited. Things get weirder from there.

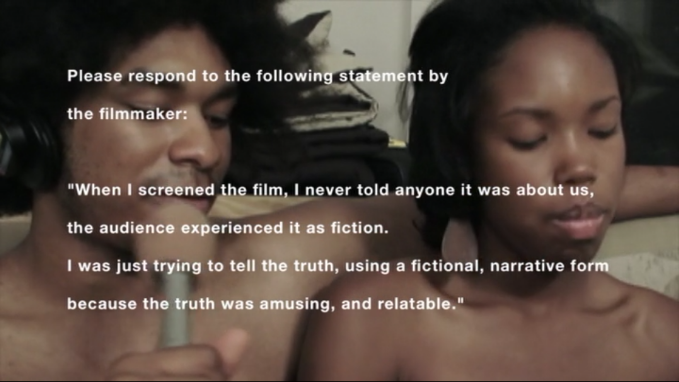

You see, the woman in the story is played by Namik Minter, the woman Nance made the short film about in the first place. Instead of making his feelings known to her, he made a short film and screened it for a bunch of their friends, including her. After getting her reactions, he chose to expand upon the original short, interrupting its run time with interludes and exegesis, utilizing animation and documentary style interviews to craft a novelistic collage that becomes An Oversimplification.

What sets this film apart from similar “friend zone” dramedies is Nance’s crippling self-awareness. He examines this one moment in time and extrapolates from all sides and angles, unafraid to draw conclusions about his own shortcomings and failings. He is harder on himself than any other subject. The film’s final third finds Nance taking Namik’s advice about a lack of female perspective (namely her own) being missing from the proceedings. This gives the story more depth and balance.

What begins as a simple tale of a bohemian twentysomething’s inability to cope with what he identifies as rejection is transformed into a cosmic rumination on the nature of love, truth, self, and beauty, all gorgeously conceived with stunning photography, emotionally resonant editing, and some truly exciting animation. It’s as “arty” as art films get without ever devolving into self-indulgent wankery. Well, that’s not necessarily true. It’s definitely self-indulgent wankery, but it’s self-indulgent wankery with heart and purpose.

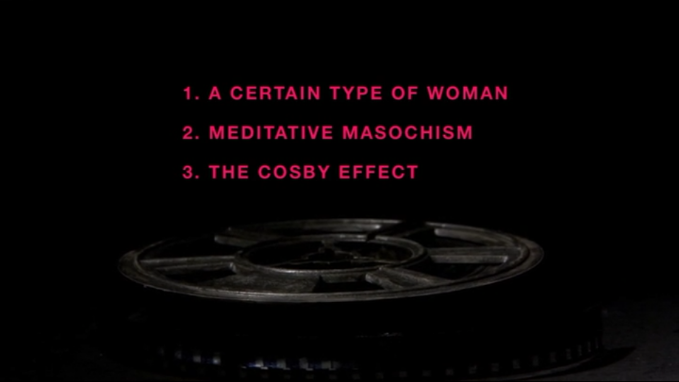

Putting most multi-hyphenates to shame, Nance acts on screen, writes, directs, animates, composes music (along with the inimitable Flying Lotus), and bares his every insecurity and blemish to craft a fully formed, expansive look at the twentysomething male condition. The resulting project shows the influence of countless sources, feeling like the midway point between Andre 3000’s The Love Below, Woody Allen’s Deconstructing Harry, Walt Disney’s Fantasia, and Junot Diaz’s short story collection This Is How You Lose Her. Realistically, many of these influences are just touchstones that I personally saw amongst the milieu, and Nance was actually channeling a myriad of cooler, more obscure sources I lack a personal connection to, but that one singular 84-minute work can call to mind artists that disparate is a testament to the uncanny energy on display.

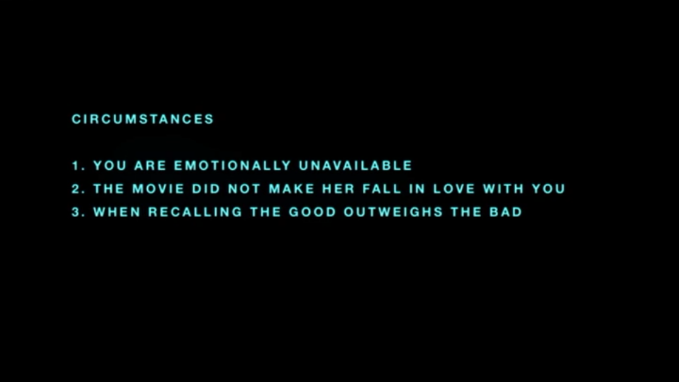

Every narrative device and artistic technique utilized furthers the same overall aesthetic. A mixture of animation and photo collage underscores a montage getting the audience up to speed on Nance’s personal relationship history. A stop motion sequence later in the film breaks down, rather coldly, Nance’s primary hang-ups in a way that is both bold and self-deprecating. There is very little dialogue, save for the aforementioned scenes where Nance interviews Namik after the initial short film. As a filmmaker, Nance uses a novelist’s time-hopping ability and marries that storytelling style to a musician’s use of pace and repetition. Specific moments are re-seen, lines of narration re-heard, all of it forming a series of bridges and refrains, harmonies reaffirming the central themes of the piece.

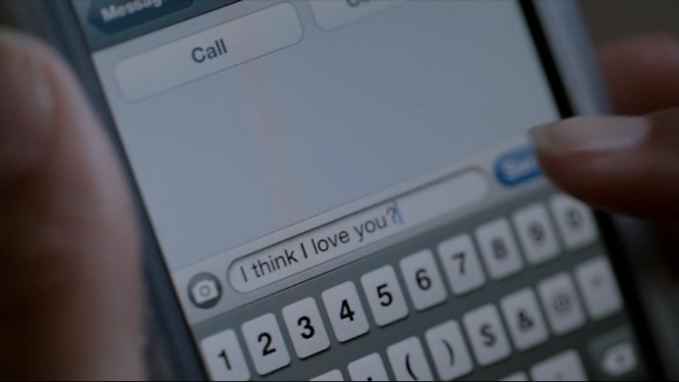

As time passes and the process of making this film drags on, Nance’s perspective shifts and we can feel a sense of growth and maturation. He puts more creative effort into seeing things through eyes other than his own, giving the story so much more emotional power than other films that trade in the same tropes. One particularly heartbreaking sequence happens late in the film, as Nance reveals a moment when Namik sent him a text message that he ignored. It was her way of trying to put their feelings out in the open, and he was too chained to his need to remain coolly ambivalent to take the bait. The way the reenactment is shot is particularly worthy of applause, using careful tracking shots to keep us in the moment.

The intersection between fiction and reality, memory and fact, leaves much room for interpretation and discussion. I imagine men and women reaching different conclusions upon the film’s closing moments, each owing to their own experiences. Cathey’s narration and the short film’s refrain “how would you feel?” take the focus off of the very specific details of Nance’s experience and enable the viewer to transpose the hypothetical to their own circumstances.

The nebulous ether which the film exists leaves us constantly wondering what is real versus what is imagined, what is lovingly recreated versus what is innocently fabricated. When Nance juxtaposes a love letter he sent Namik with the one she sent in return, the grand gesture is abruptly undercut by the revelation that she never sent a return letter, and the voice over we’ve been hearing in that sequence is something he asked Namik to write and perform on the spot since she never responded initially. Somewhere, Charlie Kaufman is clapping feverishly.

Ultimately, An Oversimplification is an astonishing piece of cinema, a colorful example of the versatility of the black voice in film, one that heavily expresses a black perspective without being exclusively mired in issues of race. Instead, we spend an hour and a half traversing the space-like ventricles of the human heart.

There’s a passage in the film that, to me, is worth the price of admission alone. When Nance is interviewing Namik, she posits that watching the initial short film was jarring because every individual has their own truth, and seeing events that transpired with you there through eyes other than your own can be difficult. It was easier for Nance to focus so much on his own inner life when dissecting being stood up, his own narration suggests, than to examine Namik or any of the other objects of his affection, because simplifying complicated beings serves one’s own narrative better. The rest of the film feels like Nance challenging himself, and his viewers to do better.

Take that, Plain White T’s.

If you have any films you would like to see covered in this column, hit us up on Twitter @DeadshirtDotNet and we’ll get them in front of Dom.