This October, Deadshirt staff revisits some of our favorite horror movies from a variety of subgenres and breaks down what makes them so memorable, so clever, and so terrifying. This week: Roman Polanski’s unsettling look at how dangerous and frightening the male gaze truly is, Repulsion.

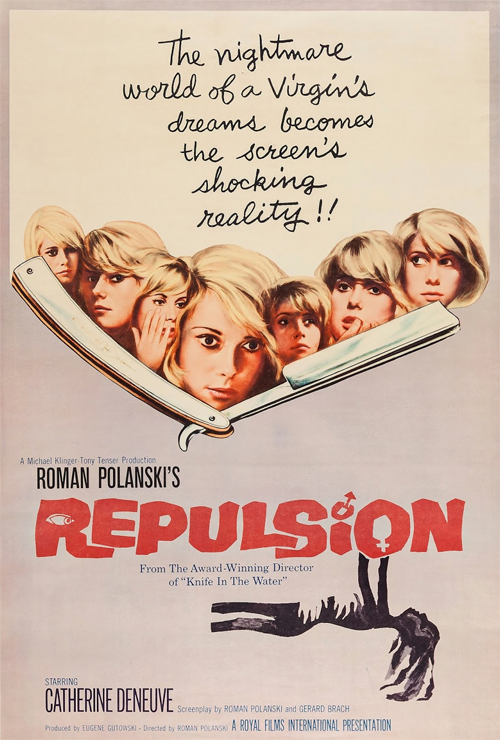

When Roman Polanski’s Repulsion was released in 1965, the tagline that accompanied the American theatrical poster was, “The nightmare world of a virgin’s dreams becomes the screen’s shocking reality!!” as you can see in the picture above. It’s a sensational and immensely pulpy combination of words that simplifies the movie’s plot and themes to their most shallow interpretation: a woman, repulsed by the opposite sex, has her worst fears realized. I’m not sure how they did things in the 60s, but 21st century attitudes towards stories of women and sexual violence have fortunately started to veer away from the basic “sex sells” attitude of that bygone era. As a more mature culture, we are aware now more than ever of certain cracks that run through society–abuse, mental illness, sexism–and the importance of narratives that bring them into the light. Repulsion is a story of a victim of abuse, faced with the everyday horror of the male gaze and male entitlement. We can never know what general audiences took away from Repulsion back in the 60s, but the movie still works as a modern horror, perhaps even more so, because the social ills from where it draws its scares are more broadly recognized today.

A warning – spoilers follow and, more seriously, discussions of abuse and rape.

Carol (Catherine Deneuve) is a manicurist living in London with her older sister, Helen (Yvonne Furneaux). She seems to be profoundly unhappy and quite possibly depressed as her life has fallen into a visibly uncomfortable pattern. She frequently falls into catatonic states at work, and outside of the salon she must deal with the constant and invasive presence of men. Colin (John Fraser) is a young Oxbridge type desperate for her company who has become unavoidable about town. Helen’s boyfriend, Michael (Ian Hendry), stays over at their apartment more and more often, encroaching upon spaces that Carol once deemed private. When Helen and Michael leave on holiday, Carol’s nervousness ramps up into paranoia.

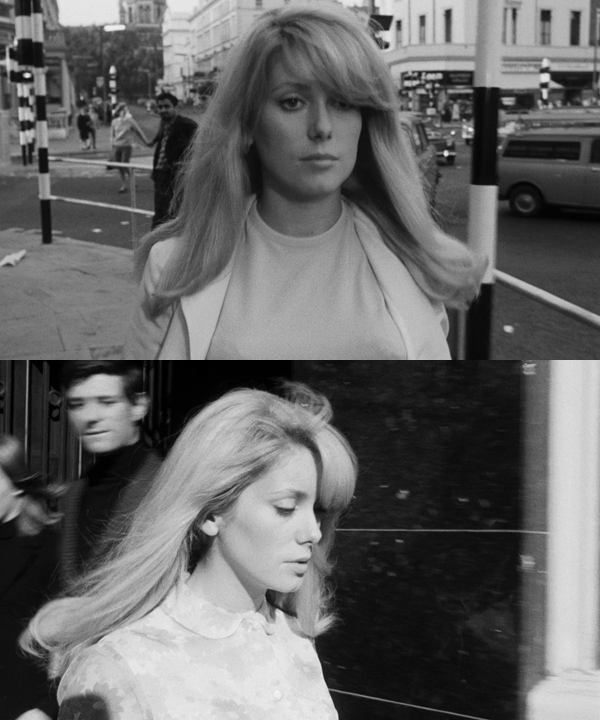

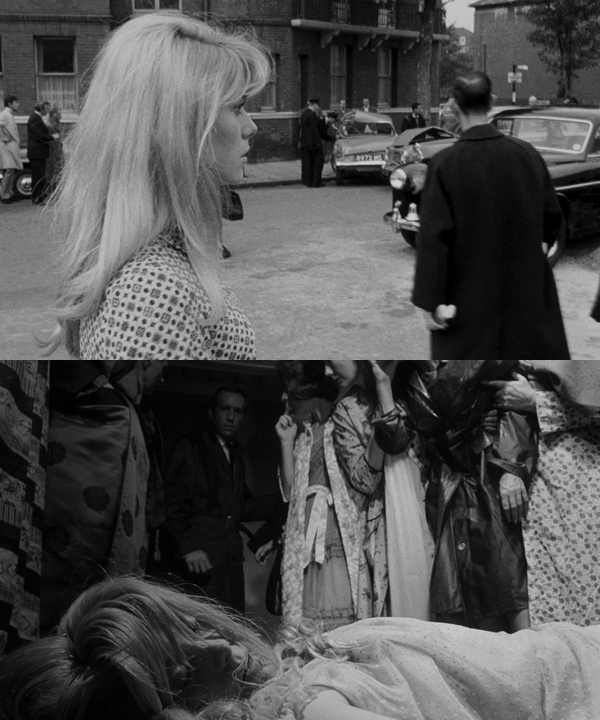

The true power of Repulsion lies not in the story we are told but in the story we see. A strong point in the movie’s favor when it comes to its modern day relevance is Gilbert Taylor’s psychologically loaded and socially conscious cinematography. Taylor’s camera highlights multiple points of view and the imbalances of power that are only visible from within that viewpoint. As the main character, Carol’s POV is the main focus, with Taylor’s camera rarely leaving her side. These shots also tend to leave Carol visible within the frame, reminding the audience that we are not looking out of Carol’s eyes as ourselves, but rather as Carol herself. Typical first person POV shots are moved to a third person vantage point behind Carol’s head while still leaving visible what lies ahead of her. Sometimes we follow Carol in a tightly framed close-up of her face, aware of both her expression and the things that are happening behind her or to her side, a sort of peripheral vision POV.

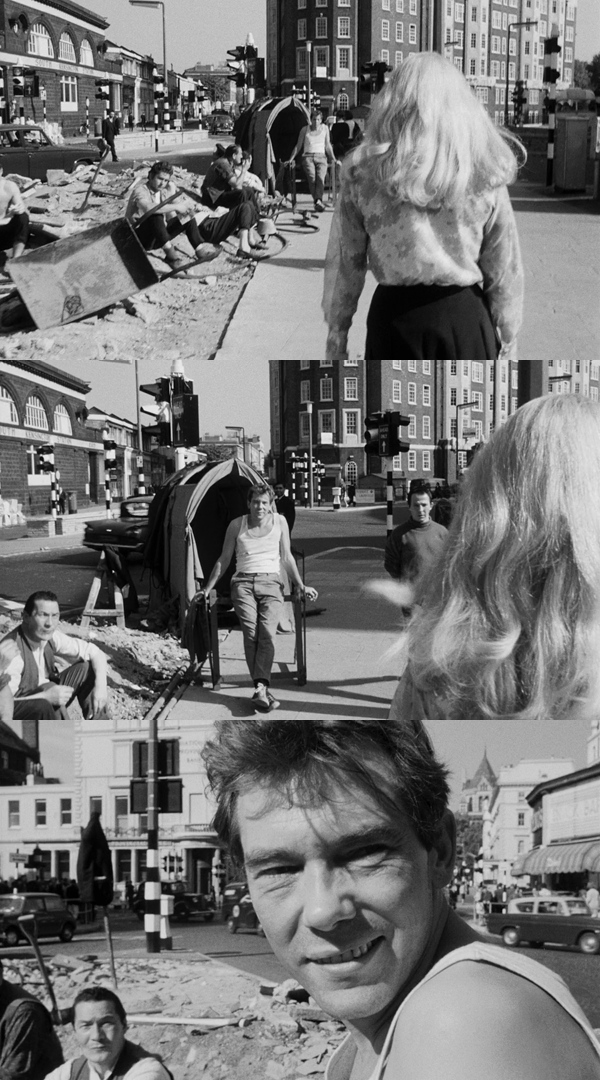

These nontraditional POV shots do much to communicate her everyday fears and nowhere is this more clearly shown than the various scenes of her walking in public. Following her from behind, we see a group of construction workers ahead of her long before they get within earshot. When we finally reach them, they catcall at her, as we sadly expected them to do. The camera drifts away from her and lingers on the main offender, giving him an uncomfortably prominent presence in the frame. Later in the film when she passes that area again, the workers are away but the camera echoes its previous motion and lingers on the empty seat where the most verbal offender once sat, indicating the lingering discomfort that his harassment has caused. In another scene, we look at Carol’s face and slightly behind her, becoming aware of the men that stare at her when she passes. Carol’s expression makes it clear that she is aware of them without even needing to look. Her daily walk from home to work becomes a cacophonous and uneasy trek within a public space where she cannot avoid the unwanted attention of others.

Taylor also constructs a sort of societal POV in his two-shots that looks at how society might erase an imbalance of power or even abuse by reading scenes of oppression through completely innocent social cues. When Colin’s advances are rebuffed, he is confused by her coldness and reacts inappropriately. He touches her hair when he runs into her at a pub and tries to hold hands with her when walking with her in the street. Michael wants to ingratiate himself to his girlfriend’s sister and does so by pinching her cheek. Both men are condescending and disrespectful of Carol’s personal space but feel like they are allowed all of this unwarranted touching because when the eyes of society are watching, these behaviors are passed off as usual or even expected of opposite-sex interactions.

Same-sex interactions are also shot with this societal POV. A bonding scene between Carol and Bridget (Helen Fraser), one of her co-workers, seems like a light moment of comfort between two women who enjoy each other’s company. However, when Bridget offhandedly mentions her boyfriend, she reasserts the status quo that two women could only ever talk about men, forcing Carol out of their two-shot and into a lonely and frustrated close-up. We are also made privy to the societal POV on men. Colin, worried about Carol’s mental state, mentions this to his two friends while drinking at a bar. They wind him up with their crass language and behavior, shooting down any of Colin’s legitimate concern with their general misogyny. They are the boys club that reinforce patriarchal ideas within other men and aim to stamp out through peer pressure anything that would go against that.

Colin becomes so frantic that he shows up uninvited to Carol’s apartment and breaks down the door. With the door ajar and another tenant stopping to watch curiously, this scene also becomes a two-shot where violence is erased in favor of a more innocuous reading. Colin’s trespass is brushed off. He even finds it somehow appropriate to tell Carol that he needs her. When he shuts the door, Carol takes the opportunity to beat him to death with a candlestick. Once something is behind closed doors, society stops watching and she knows she must kill him lest he hurt her first.

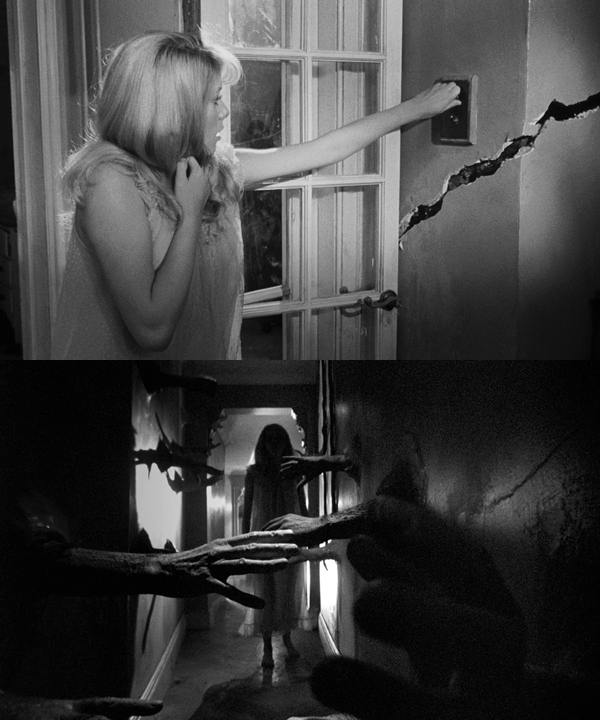

Eventually, the reality of Carol’s POV breaks down as she becomes ever lonelier, secluded in her apartment. This sometimes manifests as expressionist moments such as dramatic and structurally impossible cracks in the walls, melting, skin-like paint, expanding dimensions, and hands reaching out from the walls to grope her. At other times, these nightmares are disturbingly real. She receives phone calls with only breathing audible on the other end of the line and sees male stalkers in the corner of her eye. Most vividly, she has nightmares of being raped with no visible shift between reality and nightmare other than the sudden loss of all diegetic sound but one constant rhythm–a clock, a bell, a train crossing. These scenes are shown in disjointed and frightening ways, focusing on her scared face and her struggling hands until she wakes up. These could be explained as hallucinations caused by a schizophrenic episode, but that arguably brushes off these images as uncommon and linked to an abnormal condition. They are more plausibly (and more tragically) the echoes of a very real trauma that Carol experienced in her past, growing stronger in her physical and emotional loneliness. And while her visions are exaggerated, her fears find their basis in reality and are sadly still relatable to any woman.

The rarest but most telling shots of the film demonstrate the line of thinking that can turn what should be outlandish fears into real threats: instances of the male POV. Carol’s taciturn silence around men and her physical beauty are not and never come close to consent, but the moments of male POV show how men can twist that notion to serve their own sense of entitlement and desire. A little while after Colin is killed, the landlord comes in to find the apartment in disarray. He makes his way to the living room and the sound of flies grows louder. When we cut to his POV, however, we do not see him looking down at the rotting food that we expect but rather upon Carol, taking her in from the bottom up. She is in her nightgown, silent, nervously clutching it and thereby inadvertently pulling it up, and we see every bit of that through the landlord’s eyes. He reads the situation as a seduction and he forces himself upon her until she ends up killing him in self-defense.

When Helen and Michael return, they find a catatonic Carol hiding under a bed after discovering the other bodies. Michael picks her up in his arms and carries her out confidently. She looks at him with a face of frozen loathing but he looks at her with the expression of a hero looking upon a damsel in distress. He clearly believes that he has won her over though all he has done is help someone who never asked for his help.

In the final scene, Taylor cites the common psychological thread that runs through every moment of societal POV that he has constructed. The bystander effect is a psychological phenomenon where a group of people does not intervene to help the victim of an accident or a crime, even though they may be witnesses to the event in question. The group becomes paralyzed in watching because there is a diffusion of responsibility among members of the group. In 1964, a woman named Kitty Genovese was murdered in New York City. The New York Times reported that 38 witnesses either heard or saw some part of her murder and ultimately did nothing to help her. Although those figures and the relevance of the bystander effect in this situation have since been refuted, it is still very much a go-to example for the phenomenon. The outraged public response to its unbelievable drama was still ringing a year later, when Repulsion was made.

Taylor foreshadows his use of the bystander effect in an earlier scene where Carol walks by a car accident. Scattered groups of people stand still and simply look at the wreckage. In the final scene, Michael runs through the apartment building for a phone to call the police. The other tenants of the complex flow into the room where Carol lies and wonder about what to do. One man states twice that he will get her some brandy, but never moves from his spot. Two women pull back a grieving Helen from her sister’s body until she too becomes part of the unmoving group. A man surveying a room down the hall finds the body of the landlord and decides to turn off the light. When the violence that occurs behind closed doors is revealed, society sees what has happened as unfortunate but generally agrees that it can’t be helped. There are no longer any preventative measures to take; the violence has already happened. All that’s left is to watch until someone else takes responsibility.

The consciously female POV is still hard to find in modern cinema. Male POVs are more easily recognized and more widely discussed. Societal POVs are more accepted as truth, though they tend to lean one way and absolve tense situations of their darker meanings. Repulsion is a horror movie from the 60s that still works because it is so believably based on societal imbalances and social mores of the time that still exist today. Fifty years later, Repulsion still rings true without the need to change even the slightest detail. Nowadays we are smart enough to relegate sensational copy to slasher and torture flicks which come packaged with their own problems, but are at the very least, removed from the real. As much as we can be proud of belonging to a more mature society, the scariest part of Repulsion is how it shows us that, when it comes to real terror – the terror that women feel every day – maybe we shouldn’t be too proud just yet.

Come back next Friday for a look at another of our favorite horror movies.