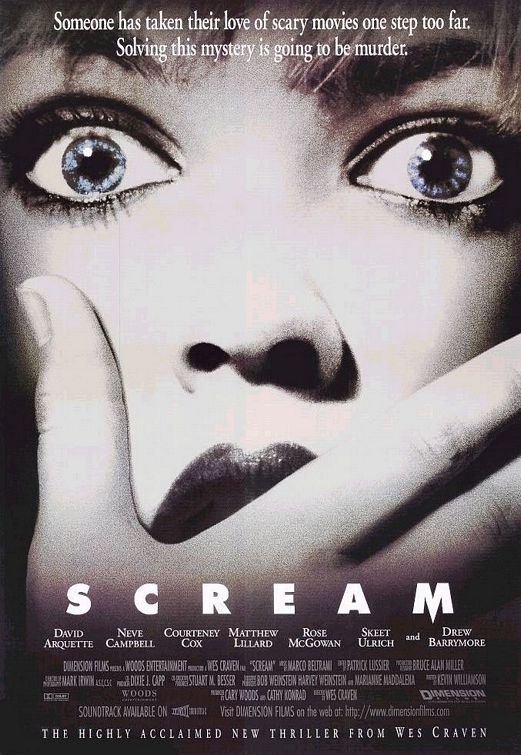

This October, Deadshirt staff revisits some of our favorite horror movies from a variety of subgenres and breaks down what makes them so memorable, so clever, and so terrifying. This week: Wes Craven and Kevin Williamson’s post modern slasher, Scream.

When the Weinstein Brothers originally tried to find a director for Kevin Williamson’s Scream script (then titled, of all things, Scary Movie), they had difficulty locking down a helmer who really got the source material. Most of the name directors they were used to working with, like Robert Rodriguez, couldn’t see past the lovingly parodic tone of the screenplay and figured it for a straight comedy. Scream is such a unique beast, not because of its self aware predilection towards distractingly meta horror movie references and 90s cleverer-than-thou minutiae, but because of how it uses those stylistic trappings to lull the viewer into a false sense of security. Thrill master Wes Craven had already successfully tread similar waters in New Nightmare, so he was a natural choice. In Craven’s capable hands, what might have devolved into a faux satiric mess became an effective, legitimately frightening horror film aimed squarely at an audience that had grown tired of the genre’s inherent tics and tricks.

Scream is basically Williamson’s love letter to John Carpenter’s Halloween in the sense that it is a slasher awash in 80s horror conventions, but spliced with whodunit DNA. Someone in a Ghostface mask is slashing up teenagers in Woodsboro, and the woefully desensitized youth of the town, still somewhat fresh from a grisly murder that took place a year ago, react to it as 90s teenagers were apt to: with clever, self-referential dialogue and a disturbing amount of aesthetic distance. The pretense that something so nightmarish could shake this town to the firmament is completely done away with, as this is a generation of kids who see people gutted on television every day. The implication of trauma at current events is instead replaced with the sense that no one you know can be trusted. From the first on screen kill, in true mystery fashion, every single individual you meet, with the exception of “final girl” Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) could easily turn out to be the knife wielding psychopath and the revelation wouldn’t raise a single eyebrow.

Before we get too deep into the film’s main plot, we have to talk about its opening sequence, twelve perfect minutes of horror served up nice for the post-Tarantino generation. Drew Barrymore’s opening scene cameo as doomed Casey Becker is up there with Janet Leigh’s shower death in Psycho when it comes to expectation-shattering stunt kills. As in Hitchcock’s classic, her untimely demise sets a tone that nothing is sacred and anything can happen. The infamous phone call, the suspenseful interplay between Barrymore and the chilling voice on the other end of the line (voice actor Roger L. Jackson, standing in for the killer’s digitized voice) is at once timely and iconic in the way, say, Speed‘s “pop quiz, hotshot” bit is, but it is also economical and functional. Acting as a primer for the film to follow, Ghostface’s initial phone call lures us in with wit and mystery. The banter is pointed, but playful. The “what’s your favorite scary movie?” line may have grown a thick moss of obsolescence over the years (the The Matrix bullet time of horror dialogue) but the discourse it opens up is crucial. This is a horror film designed to prey on people who think they’re too smart for horror movies.

From Casey Becker’s opening critique of genre tropes through every character’s in-story qualms with the way horror movies function, the filmmakers are putting their audience up on the screen. Immediately, we relate and identify with these teens in a way that we don’t with the usual faceless lambs lined up for the scream screen slaughter, but here, in their self awareness, we find a kinship. It’s pretty easy to talk mad shit about fictional victims and how they always run upstairs instead of outside, but when you’re the one on the other end of the line and your boyfriend’s insides are decidedly outside, it’s not so easy to fucking quip. Craven’s slow push in on Casey’s face as she realizes this predator on the phone is not fucking around says it all. The fluidity in the blocking and editing naturally shifting gears from Pillow Talk telephone banter to Sorry, Wrong Number histrionics is impressive and reminds you from jump street that no matter how cute the references get, all the slick chat ends with knives in ribs. (Using Jiffy Pop in lieu of a tea kettle on the stove as a suspense-building device is a nice touch.)

In Sidney Prescott, we have a Final Girl/Virgin to stack up to the altar of Jamie Lee Curtis. In Sidney’s first encounter with the killer, we see her go home alone to one of those far out houses Casey lived in, not so close to neighbors, not so accessible to police. The mirror image calls back to the film’s opening and its grotesque conclusion, but Sidney is different. Where Casey resorts to name calling and false bravado, Sidney calls the killer on his bullshit and sneers right back. At first, Sidney seems pretty harmless and her squeamishness at all the scandal seems rote, but the reveal that her mother was brutally murdered and assaulted the previous year explains it all. Maureen Prescott’s murder, though off-screen backstory, looms over the film’s proceedings, as if her death ripped a band-aid off this scab of a town, leaving all manner of pus and blood to fester. Her entire world is a reflection of that lurking evil.

Her boyfriend Billy Loomis, played by a Skeet Ulrich who might as well have “Johnny Depp Stand In” tatted on his forehead, pressures her for sex. Her best friend, a pitch perfect Rose McGowan, pals around with a casually sociopathic Matthew Lillard. Her nerdy friend Randy (the best character Jamie Kennedy has ever played) is clearly in love with her in what can be viewed as a predatory friend-zone kind of way. Her distant, yet protective father is presented as a red herring cypher whose literal absence through much of the film allows a suspicious audience to project all manner of misdeed. Outside of the somewhat frustrating addition of David Arquette (as bumbling, half charming Deputy Dewey) and Courtney Cox (as a really unlikable pseudo Lois Lane), the entire cast is immaculately conceived as a vast manifestation of the fear and unease Sidney feels wherever she goes.

Craven uses this suburban paranoia to great effect. One of my favorite examples of this is the strange small part Henry Winkler plays as their school’s principal. When Sidney is brought into his office to talk to police early in the film, Winkler dotes on her in a manner that is beyond discomfiting. He reassures her by cupping his chin casually in his hands, an invasive moment marked with a sharp cut to the police officer, who clocks the gesture. That cock eyed glance encapsulates how we, the audience, treat every character we encounter. Every line of dialogue, though kitschy and self congratulatory in that 90s movie kind of way, becomes an accidental double entendre, either supporting or negating the case we build up in our minds as to the killer’s true identity.

This weirdness with Winkler intensifies later when he expels two students for dressing up like the killer as a prank. He wields a pair of scissors at them with a ferocity that continues to unsettle. It would be easy to sell Winkler as the killer, a loving but misguided authority figure teaching these youths a lesson. He’s killed shortly thereafter, though, so, you know, it’s not him.

But that it COULD be him is one of my favorite things about Scream. You could have released a cut of the film with ten different endings, like Clue, and found enough material to believably support each of those outcomes without detracting from the film’s tone and themes. The anonymity of the Ghostface mask and the fake voice presage the abuse headquarters of internet comment threads as the killer mocks, debases, and taunts with horror movie trivia and a sort of haunting omniscience. The film’s final set piece, a high school party, provides a set of scares that remind you the extent of Craven’s powers. As Randy comically lists off the “rules” of horror movies, we see the rules in action, with Sidney finally giving into Billy’s pleas for sex. This scene smartly mirrors the “PG-13 relationship” talk they have when we first meet them, the difference in her decision a commentary on what Sidney’s been through and who she is now.

From there the kills and contrivances form a clever rendition of the board game Guess Who, every suspect either ruled out by being killed or otherwise crossed off by logic. The decision to reveal the identity of the killer works for the finished product, thematically furthering the central theme of pop culture wise suburban kids fucked up by the movies they grew up on, but I can’t help but think the reveal is irrelevant. Craven and Williamson crafted a film that cut through all the bullshit that kept then-modern audiences from being able to suspend their disbelief with horror films. By playing it straight with the absurdity of the tropes we’d all gotten so innoculated to, they were able to misdirect viewers long enough to really stick them with some visceral thrills in a story about just how fucked up the real world got.

There’s a point where Sidney reminds Billy that this isn’t a movie, but real life. He reminds her, someone metatextually, that life is just one big movie, and you get to choose the genre. This film knows if you’ve come to see a movie called Scream, you’ve already made your choice. There’s no need to pretend you’re some novice who doesn’t know the basics. It reminds you that you’re never too clever to be scared, because you’re never truly above danger, whether it comes from your neighbors, complete strangers or the video you pop in on a Friday night to escape reality. Screams 2 & 3 riff on these central themes to varying effect, and 4 nearly succeeds in rebooting the entire premise, but the original was a real shocker that reminded us what horror was capable of while keeping us busy with our own obsession with nostalgia and patting ourselves on the back.

Come back next Friday for a look at another of our favorite horror movies.