We’re spending the month of December looking back at some of the great new releases that we missed out on reviewing earlier this year. This is The Rest of 2014.

There’s a certain kind of indie film I tend to avoid, and based solely on what little I knew of The Skeleton Twins, it felt akin to that skippable milieu. You know the type. Comedic actors playing “serious” roles contemplating the nature of life while cloying Barnes & Noble in-store listening selections play, all framed like a film school dropout has seen Garden State too many times. I only gave this film a pass because I Really Like Bill Hader, but I’m pleased to report that it is something special.

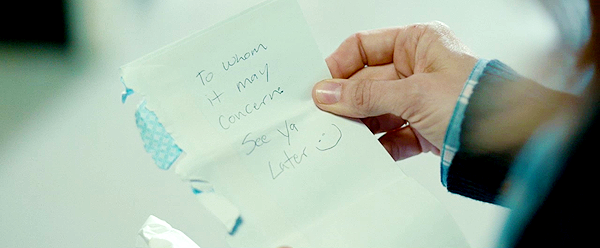

The Skeleton Twins tells the story of a close knit brother and sister, Milo (Hader) and Maggie (Kristen Wiig), who have spent their entire adult lives recovering from the suicide of their father when they were teens. When we meet Milo, he’s drinking vodka straight from the bottle and writing his own suicide note on the side of a used envelope. Maggie is on the other side of the country, ready to swallow a fistfull of pills, when she gets the call that her brother has tried to kill himself. It’s an efficient bit of character introduction that smartly tempers the heavy subject material with just the right amount of dark humor. The image of Bill Hader naked in a bathtub bleeding out is a lot easier to stomach as a viewer when juxtaposed with this ridiculous note.

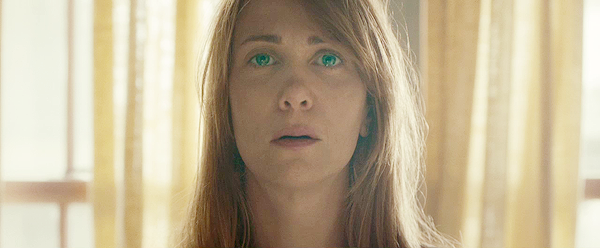

The siblings haven’t spoken for a decade, but Maggie convinces Milo to come back home and stay with her and her husband Lance (Luke Wilson), setting off the main thrust of the narrative. That we meet Maggie in that moment of morbid vulnerability colors this otherwise typical premise in a much more fascinating light. For Milo and everyone else, she plays the role of protective big sister who’s got her life together, but Wiig effortlessly expresses a troubled inner life, creating an engrossing tension even in the film’s many quieter, plotless scenes. Lance and Maggie are the model suburban married couple, and the dichotomy between the Maggie we see with Milo (the caustic and irreverent troublemaker) versus the salsa-lesson-taking housewife she pretends to be engenders an altogether different type of sadness from Milo’s self-professed “melodramatic gay tragedy.”

The film offers two divergent paths of adulthood after childhood trauma, each presented with a even-handed sense of non-judgement. Milo and Maggie are both flawed, at times difficult to like people, but Hader & Wiig are both such intensely lovable performers that you’re able to overlook these immediate deficiencies and soldier through the difficult adventure that is adult life without criticizing them too harshly, even as we watch them both repeatedly err towards a frustrating self-destructive streak. Milo, with his cattiness and his excessive drinking, and Maggie, with her constant deception, both casual (secretly taking birth control while trying to have a baby with her husband) and overt (cheating on Lance with the men she meets at her extracurricular classes).

While it should be no surprise that Hader & Wiig deliver two of the best performances of the year, new filmmaker Craig Johnson (who co-wrote the script with Mark Heyman) proves himself a welcome new voice in cinema. The writing is sharper and feels more true to life than a lot of similar fare on the festival circuit, making The Skeleton Twins arguably one of the funniest films of 2014 despite being largely preoccupied with suicide, depression, and other difficult to sugarcoat mental health topics. It bridges a nice gap between the socially conscious, dark humor of a Hal Ashby film and something Harold Ramis might have given us. At times, the interactions between brother and sister prove a little too cutesy or on the nose, but it’s balanced out well by later sequences in which the tension between them bubbling under the surface bursts out in harsh, all too real ways.

Cinematographer Reed Marano bathes our principal characters in a light that is near blinding, undercutting the relative darkness hiding in the shadows of the bags beneath their eyes. Visually, the film is a surprising treat, artfully utilizing some intermittent halloween imagery to spruce up the otherwise familiar terrain of talky dramedies set in typical-looking houses. The only place the filmmaking leaves anything to be desired is the film’s score, which honestly feels better suited as background noise for a Nissan commercial than something as singularly witty and heartfelt as this film. The soundtrack, however, more than makes up for this, as sort of a proto-Sadderday version of the Guardians of The Galaxy mix, serving up OMD and Starship as cathartic ice breakers between many of the film’s harder to swallow moments of emotional honesty.

I applaud any film brave enough to handle such difficult subject matter, from the ongoing after-effects of losing a parent to suicide, to a particularly thorny subplot about a relationship the teenage Milo had with his doting English teacher (a well-cast Ty Burrell), never taking the easy way out. Luke Wilson deserves some kind of special consideration award as Maggie’s husband. Not since The Royal Tenanbaums has he been so fascinating on screen. Indie comedies, take note. If you’re going to flip the script and try to Little Miss Sunshine your way into critical acclaim, it’s not enough to flip the switch from a smile to a frown. You have to craft stories about people who feel real, then you can let your audience laugh and cry accordingly without needing to pander one way or the other. The Skeleton Twins succeeds on both fronts, because its main concern is to make you feel something.