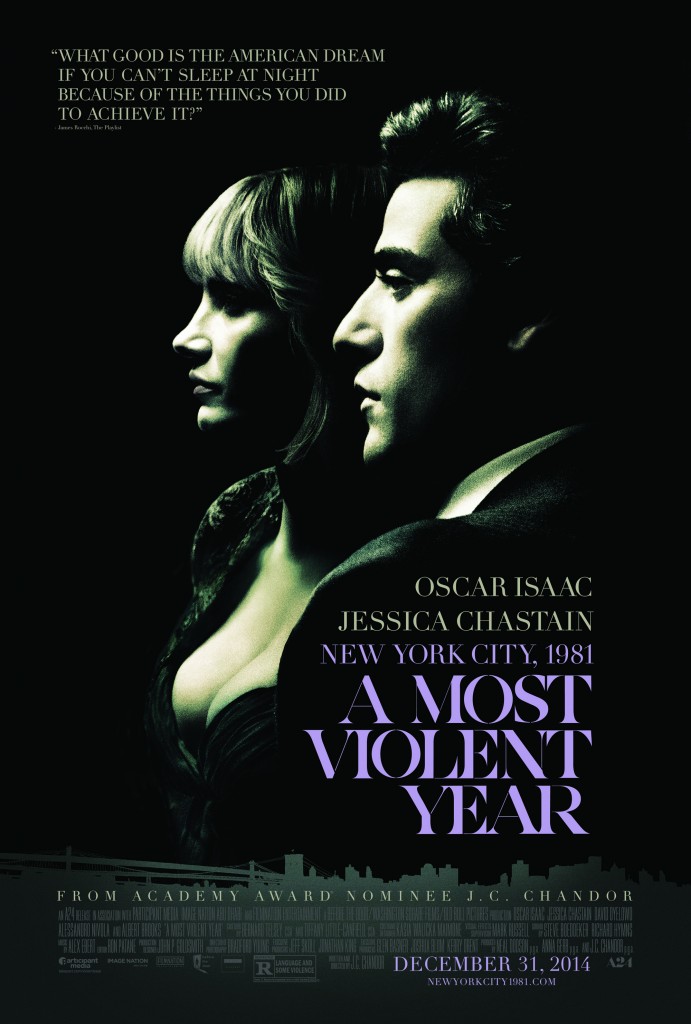

Based on nothing but early trailers and the visual motifs of the marketing material, A Most Violent Year looks like the most overlookable film of the last year. Oscar Isaac with his young Al Pacino impression and that stark pink and purple lettering over dark, moody New York imagery (A24 is nothing if not brilliant at crafting striking ad campaigns) just scream that this is a modern throwaway throwback to the kind of gritty movies Sidney Lumet and Harold Becker used to make. Luckily, writer/director JC Chandor has something a little more substantive up his sleeve.

A Most Violent Year is the latest in a recent wave of films explicitly about the American Dream, succeeding on the strengths of its performances, the steady hand of its direction, and the sumptuous chiaroscuro of its cinematography. Oscar Isaac plays Abel Morales, a cripplingly honest man whose oil business is beset on all sides by a series of threats, from his competitors, from the thugs who keep hijacking his trucks, and from the Assistant District Attorney (David Oyelowo) working to bring him up on charges of fraud. Abel has thirty days to close a deal on a piece of land that will finally take his business to the next level, but these outside forces conspire to unravel his entire life’s work.

At his side, there’s his lawyer, Andrew (Albert Brooks), a warm and welcome comedic presence, adding a pragmatic sort of levity to the proceedings, and his wife, Anna (Jessica Chastain), a gangster’s daughter with hot temper. While she’s his partner and supports his moves, there’s a growing frustration within her as Abel continues on a straight and narrow path that runs perpendicular to the increasingly crooked world that surrounds his slim bubble of honor and integrity.

Abel considers himself a self-made man who doesn’t cheat to get ahead. Others may find his industry to be unscrupulous by definition (the film seems to posit that all of capitalism is, in some way or another, just as crooked as any criminal empire), but Abel doesn’t see it that way. When he has to console Julian (Elyes Gabel), his driver who’s been beaten in a recent hijacking, there’s a palpable derision in his voice for the men who committed this crime, and it’s not just because they took something that belongs to him. The prospect of resorting to thievery just doesn’t compute for him. He’s a man who scraped from the bottom to climb to the top of a mountain, with his nice home, his white wife, and his immaculately slick hair, a status the shell-shocked Julian clings onto as inspiration. Two scenes flip this relationship in heartbreaking ways: the first, when Julian tries to confide in Abel while speaking Spanish and Abel demands he speak English, and another, when Abel manipulates Julian’s wife (Catalina Sandino Moreno) by code switching back to his native tongue. The lengths he’s gone to assimilate are as impressive as they are disappointing.

Isaac plays Abel as such a straight arrow, a man for whom criminality and graft are foreign, incalculable concepts. His performance is a little impenetrable when the film begins, but the slow burn of watching this man’s back get pushed tighter and tighter against a wall brings out some of the best work of his short but impressive career. The very Glengarry-like scene of him teaching a new sales associate how to talk to clients is chilling, and there’s this cool thing he does with a forehead vein in a later scene with Moreno that should have been nominated for an Oscar.

There’s something purposefully misleading about Isaac’s Michael Corleone cosplay, tricking you into thinking we’re watching the birth of some swagged out crime lord, but there’s a messiness to the film’s arc that is considerably more resonant than that well-worn trope would have been. Abel has a vision for the way his life is supposed to go, and life happens to have some “creative differences” regarding that vision. Instead of watching a man give into the easy way of doing things, we’re instead forced to watch him brought lower and lower, from having to beg for loans hat in hand from his rivals to being (justifiably) emasculated by his wife. The latter is beautifully framed in a scene in which Abel and Anna hit a deer and Abel doesn’t want to get his hands dirty to put it out of its misery, so Anna shoots the shit out of it from the car.

In his own mind, Abel is a mythical hero who’s followed the narrative of the American Dream to a T, but Alex Ebert’s score, a mixture of traditionally manipulative orchestral instrumentation with eighties-appropriate synthesizing, gifts him a theme that is at once noble and triumphant, but bent with a self-defeating wilt that reminds you how unreasonable his refusal to compromise really is.

The thing that makes this film so vital is how it’s a stressful, heavy slice of life masquerading as a stylized crime thriller. The trailers haven’t lied to you. All the elements you want from a movie called A Most Violent Year are present, but not in the genre-fulfilling forms you may hope to be sated by. There are guns, but when they go off, there’s no voyeuristic thrill to be had. The shots are loud, shrill and discomfiting. The film’s finest moment comes near the third act, when Abel finally finds himself in pursuit of one of his hijacked trucks. The sequence is riveting, but not in the high octane sense most car chases aim for. There’s a mixture of anxiety and inevitability about it that churns your stomach. It gives way to the best cinematic foot chase since the opening of Joe Carnahan’s Narc, as Abel chases one of the thieves (played by Charlie from Girls in the most pistol-whippable role in the film). The running is perfectly set up by the opening images of the film, when Bradford Young lenses Abel’s morning run. We know he’s prepared for this kind of marathon, because his entire life has been a marathon, unlike this crook who’s just in it for the sprint.

Speaking of Bradford Young, an incredible cinematographer who shot both this and Selma in the same year and still didn’t get any Oscar love, does some amazing things visually here. Chandor’s made one of the least subtle films you’ll see this year, but Young helps to craft images that at least mete out the director’s blatant symbolism in a shrewd and striking manner, especially the way he lights and frames snow. For much of the film’s run time, flakes have accumulated on the ground as a white blanket of purity, but in key moments, when blood and oil seep into the snow, or we see characters standing in streets where the snow has been driven over, plowed through, and otherwise inexorably tinged with dirt, we have a stronger understanding of what Abel and his family have been through, and what’s been sacrificed for their success.

Everything has a price, and there’s a thinner line between breaking the law and being an honest businessman than Abel can bring himself to understand.

A Most Violent Year is out now in theaters.