I’ve theorized, for a while, that Grant Morrison really has two primary “tracks” of work, which developed almost simultaneously at the beginning of his tenure at DC, just as he was breaking into American comics. They certainly don’t encompass his entire oeuvre by any means, but they’re a fairly consistent dual lineage of theme, idea, and style. They’re both unmistakably very Grant Morrison in approach—digesting, internalizing, and resynthesizing a mix of obscure and popular culture in new and unexpected ways—but apply that algorithm to different libraries of material. There’s the superhero comics, metafiction-obsessed Grant Morrison we met in Animal Man, with a love of remixing and polishing previous superhero comics ephemera, and the occultist, big-R Romantic Grant Morrison, dealing with (to the layman) obscure occultism, sexual exploration, and existential dread we got introduced to in Doom Patrol.

I’ve theorized, for a while, that Grant Morrison really has two primary “tracks” of work, which developed almost simultaneously at the beginning of his tenure at DC, just as he was breaking into American comics. They certainly don’t encompass his entire oeuvre by any means, but they’re a fairly consistent dual lineage of theme, idea, and style. They’re both unmistakably very Grant Morrison in approach—digesting, internalizing, and resynthesizing a mix of obscure and popular culture in new and unexpected ways—but apply that algorithm to different libraries of material. There’s the superhero comics, metafiction-obsessed Grant Morrison we met in Animal Man, with a love of remixing and polishing previous superhero comics ephemera, and the occultist, big-R Romantic Grant Morrison, dealing with (to the layman) obscure occultism, sexual exploration, and existential dread we got introduced to in Doom Patrol.

What’s fascinating about these two tracks of work is less how they differ than how they reflect. While the surface-level reference files and commercial success levels of these Grant Morrisons have differed considerably, what hasn’t is their thematic content. Animal Man and Doom Patrol both dealt with broken people and concepts rebuilding themselves, and the power of support systems and family. The Invisibles and JLA explored humanity rising up and uniting to a glorious new millennium, while New X-Men and The Filth dealt with moving on, growing and rebuilding after the devastation of that dream. Morrison’s long run on the Batman books seemingly converged those two strands for a while, since Batman’s one of the few superheroes believably hip to all the weird shit Morrison usually writes about in his creator-owned work, a character and mythology versatile enough to encompass both Darkseid and Baphomet.

That run’s been a year and a half gone, though, and now he’s reunited with his well-oiled collaboration machine from the final year and change of that run, Chris Burnham and Nathan Fairbairn, for Nameless. Incidentally, Nameless is running simultaneously with the last few issues of his much-ballyhooed, long-anticipated The Multiversity for DC Comics. Much like the abovementioned pairings, while they pull their reference material from different libraries, the stories are—at least at this stage—remarkably similar in theme: as Morrison put it in his interview with Matt D. Wilson, “be careful what you let into your head.”

In The Multiversity, the dark ideas come in the form of the Gentry, hyper-exaggerated supervillain archetypes acting as the servants of the mysterious Empty Hand who enter your consciousness through comics, taking root and sporing to destroy your self-esteem and, eventually, your life. Here, it’s in the form of sigils, Mayan mythology, and John Dee‘s Hermetic magic—as much Morrisonian mainstays as superheroes who know they’re comic book characters with their fates decided by the whim of editorial departments. The shared message is powerful and clear: garbage in, garbage out.

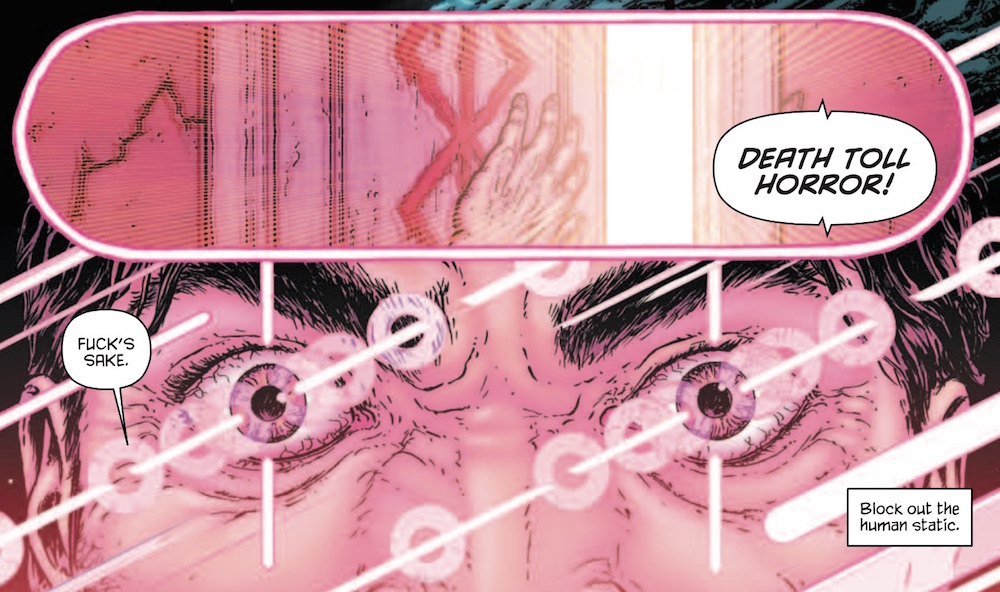

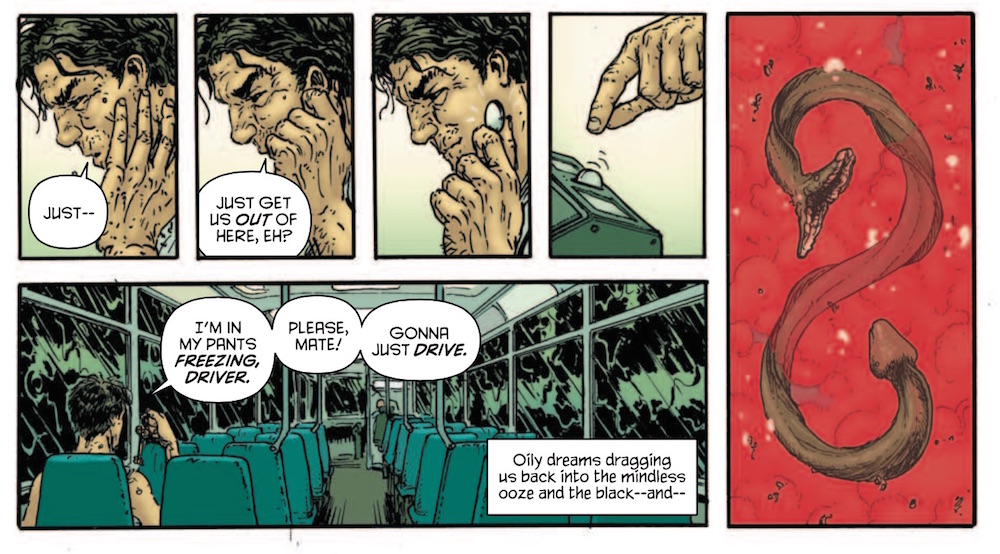

Nameless stars a currently-nameless occult expert/dream invader, a Scottish Dom Cobb who says “cunt” a lot (you can tell Morrison has a lot of fun digging into working-class Scottish brogue again) living in a world full of acts of unimaginable, all-encompassing evil perpetrated by unexpected agents with inexplicable motives. (In other words, the one we live in.) He gets in over his head on a job, and is then rescued and hired by a mysterious “billionaut” to save the world from a mysterious occult threat by…well, that would be telling, but the cover definitely provides an ample clue. Nameless is the kind of book where, so far, specific plot details seem less important than their meaning. However, it’s a book where the first half takes place in a dream, with all of the semiotic anti-logic that entails; a dream world where you can let people into your head and they can steal your secrets and use them against you in reality.

These varying levels of reality and consciousness are expertly rendered by the Batman Incorporated Dream Team, Chris Burnham and Nathan Fairbairn, who, along with Morrison, have developed a superb rapport where it’s difficult to discern where one begins and the other ends. Did Morrison dictate a certain color choice in the script, or did Fairbairn intuit it from the story? Is a dreamlike page layout from Morrison’s imagination or Burnham’s? It’s difficult to tell, and I’m not sure I want to know. Morrison has inconsistent relationships with many artists, but has always had a core circle of symbiotic collaborators. Burnham’s in that circle with the likes of Frank Quitely, Cameron Stewart and Frazer Irving, with layouts both simple and ambitious that are always crystal-clear and eye-guiding, and figure work and detail that’s pleasing when called for and appropriately repellent when not. Fairbairn’s expertly colored everyone on that list who doesn’t color their own work, more of a storyteller than an embellisher, always accentuating rather than overpowering the work of the writer and line artist while never underselling his own considerable technical skill.

Is it an easy-to-digest read? Fuck no. Is it obtuse, willingly obscure, and referential to shit you can only find in poorly-lit, weed-stench-laden basement bookstores in college towns? You betcha. Will this first issue make sense in its entirety until the last issue is out? Not a goddamn chance. I didn’t get to read The Invisibles or The Filth while they were coming out, but I’m willing to bet the opening salvos of those stories felt a lot like this: “I have no idea what I just read, but I think I like it, and I trust Grant Morrison to have it all make sense in the end.” He’s certainly whiffed the narrative ball before—The Mystery Play is almost famously disastrous, and I thought Happy! was an unsatisfying mess (although I haven’t read it since its initial release)—but here the odds are more stacked in his favor: not only is he working with the sort of occult material he’s familiar with and used to his advantage before, but he’s backed up by an artistic team he melds with brilliantly, complementing rather than clashing with his esoteric ideas, visually translating them even when you have no idea what the words on the page mean.

It’s complex, it’s pretty, it’s clever, it’s mysterious, it’s fucked up. I’m glad I let it into my head.

Nameless #1 hits shelves tomorrow, digitally or at your local comics shop.