Diversity and representation have long been a serious issue in the film industry, and 12 Years A Slave winning some Oscars hasn’t exactly changed that. Outside of that prestigious anomaly, people rarely imagine black film to be much more than gangster movies, cookout comedies, and Tyler Perry. Our very own Dominic Griffin will prove otherwise, shedding a light on unsung, underrated, forgotten and new films that show the breadth and versatility of the black voice in film. Named after one of Billy Dee Williams’ affectionate nicknames, this is Dark Gable Presents…

As a moviegoing culture, we seem to decry remakes with the exact frequency with which we pay to see them in theaters. Remakes are, by and large, used as a talking point for the argument that originality is dead in modern cinema, that studios are afraid to take risks with brand new material and want to rely on something that has already worked in the past, a vicious indictment that tends to leave out the complicit audience in this cycle of recycling. Studios, and by extension, some of the artists that work for them, take fewer risks because of the ever-hovering specter of financial viability. The worry that no one will see the film and that economic eventuality making it difficult for them to get work in the future suppresses filmmakers into a creative holding pattern.

There are only two good reasons to remake a film. One, the original film is Not Very Good and you can improve upon it in some way, like Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven, or two, the original film holds some special importance to you and you want to contemporize the narrative to bring more attention to the source material.

Spike Lee’s latest film, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, which he funded through Kickstarter, is an explicit, if confounding remake of Bill Gunn’s superior 1973 film, Ganja & Hess. The two films share a near-identical plot, but their themes and concerns are as disparate as the stylistic approaches of their respective helmers.

The financiers behind Ganja & Hess were clearly hoping for a Blacula-esque blaxploitation film, but playwright/filmmaker Bill Gunn turned in a very different finished product. His take on the “vampire movie” is restlessly innovative and relentlessly experimental, as fiercely personal a film as one could imagine in any genre. The basics of its plot belie an increasingly complex structure and narrative style that makes the story worth telling.

From jump street, Gunn makes it clear that this is a movie about a man who subsists on blood, through a fascinating mixture of storytelling devices. Reverend Williams (Sam Wayman) begins describing the curious plight of Dr. Hess Green (Night of The Living Dead’s Duane Jones), a man he chauffers part time, through Nick Carroway-style voiceover narration, right after the film’s opening titles outline his origin story of sorts. Hess is an archaeologist whose mentally unstable assistant, George Meda (the director, Gunn) stabs him with an African ceremonial blade, unintentionally gifting him with immortality and plaguing him with an addiction for blood. The titles and the voiceover both tell us about scenes we’re about to watch actually unfold, so you might feel they’re extraneous, but the conflicting tones they present in triplicate, from the omniscient preamble, to Reverend’s perspective, to Meda’s, sets up the rich, dense feel that’s cultivated by the film’s remaining run time.

Gunn’s Meda is an incendiary presence on screen. Vibrant, but unhinged, his performance is one of the liveliest I’ve ever witnessed, adding heft and pathos to the sudden act of violence that effectively jump starts the plot. Unlike most vampire films, Hess figures out his predicament rather quickly, awaking from “death” to find his killer having already committed suicide. Hess drinks Meda’s spilled blood and begins to figure out how to survive, first, in a brilliant brusque vignette in which he steals blood from a clinic, then subsequently in disturbing scenes in which he kills and feeds from prostitutes. The allegorical nature of his vampirism, thinly veiled social commentary about bourgeois blackness, matters more than any accepted ephemera of horror, ie, no silver bullets, wooden stakes, or weakness to sunlight. The cross remains, for its symbolic power and representation of Christianity.

When Meda’s erstwhile spouse, Ganja, turns up, seeking her husband, things begin to shift. Marlene Clark’s performance here is fantastic, like a cross between Katharine Hepburn’s celluloid confidence by way of #blackexcellence. Her character is somewhat frustratingly framed as being as vampiric in attitude as Hess is, but this is largely the result of the film’s narrative perspective, which, while switching between Hess and the Reverend and Meda, doesn’t give Ganja much agency until later in the film. Ganja and Hess’ initial courtship comes to an end when she discovers her husband’s dead body, and all bets are off. From there, they marry, and Hess conscripts her into his life of blood drinking and godlessness, a life he himself appears to grow increasingly tired of. Ganja rejects this new status quo at first, in a harrowing scene in which she makes her first kill (a handsome young man the couple has brought home), but when Hess reaches his limit and discovers the only way for their kind to die, to accept the Lord and finally fall in the shadow of the cross, he does so alone.

Ganja decides to keep their way of life, and the film ends with her starting a new chapter, the thought-dead victim of her first feeding as her new partner.

I love Ganja & Hess because its plot can be pretty easily explained in a few sentences, but the themes and the meaning between the images used to convey that story could be dissected forever. It’s a rich piece of work ripe for examining and tearing apart with no shortage of interpretations. Although pure in the distinction of it’s authorial voice, it calls to mind the experimentation of early Godard, or the fever dream allusions of Jodorowsky. It’s not hard to see why Spike Lee would want to remake it.

His remake just sucks.

Let me ‘splain. In Ganja, the artifact that Meda stabs Hess with, thus cursing him to eternal blood lust, is a small blade fashioned out of bone. It’s so small and obscure that it was impossible to screenshot a frame that clearly showcased it. Here is the same blade in Da Sweet Blood of Jesus:

This one frame is pretty emblematic of the entire film. Where Ganja was a slim dagger to the heart, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus is a giant, blunt object, bludgeoning you in the fucking head repeatedly. Everywhere that Bill Gunn chose to let silence or Ganja‘s perfectly curated music speak for the film, Lee fills with Bruce Hornsby’s oppressively plaintive piano or an increasingly annoying and scattershot soundtrack. While Lee follows the plot nearly beat for beat, much of the dialogue is entirely his. Characters are always one step away from turning to the camera and reading Spike’s thoughts on social issues aloud. I started to jot down every idiotically overt line of dialogue he had added to the otherwise spare source material, but stopped when I realized I was just transcribing the entire screenplay.

Usually, when a film treats its audience like fools and feels compelled to overly explain every nuance, it’s because some studio or test audience doesn’t trust it and wants to whittle it down to the lowest common denominator. This is the dreaded middle man that filmmakers complain about when working with larger budgets. It’s the very reason they retreat to independent productions and crowdfunded projects, you know, like this one that Lee made. Who’s to blame for the dumbed down take on the material if his entire reason for asking for the audience’s money was to work free of interference?

At this point I should make it clear that I legitimately love Spike Lee and consider him to be one of my favorite living directors. Even when he errs, he’s one of the most exciting and interesting voices in film. You’re reading words written by someone who has seen She Hate Me more than once, someone who sincerely dug elements of Lee’s Oldboy remake, so don’t mistake this invective for “haterade.” I’m just seriously fucking disappointed. Gunn’s original film has a few obtuse moments that require you the viewer to really examine and interpret what you’re seeing, but that active participation makes the film so much more involved. It draws you in and gives you reason to follow the story through to its conclusion, where Lee’s remake feels the need to explain every ambiguity, to pin down every nebulous element like a butterfly impaled on a push pin.

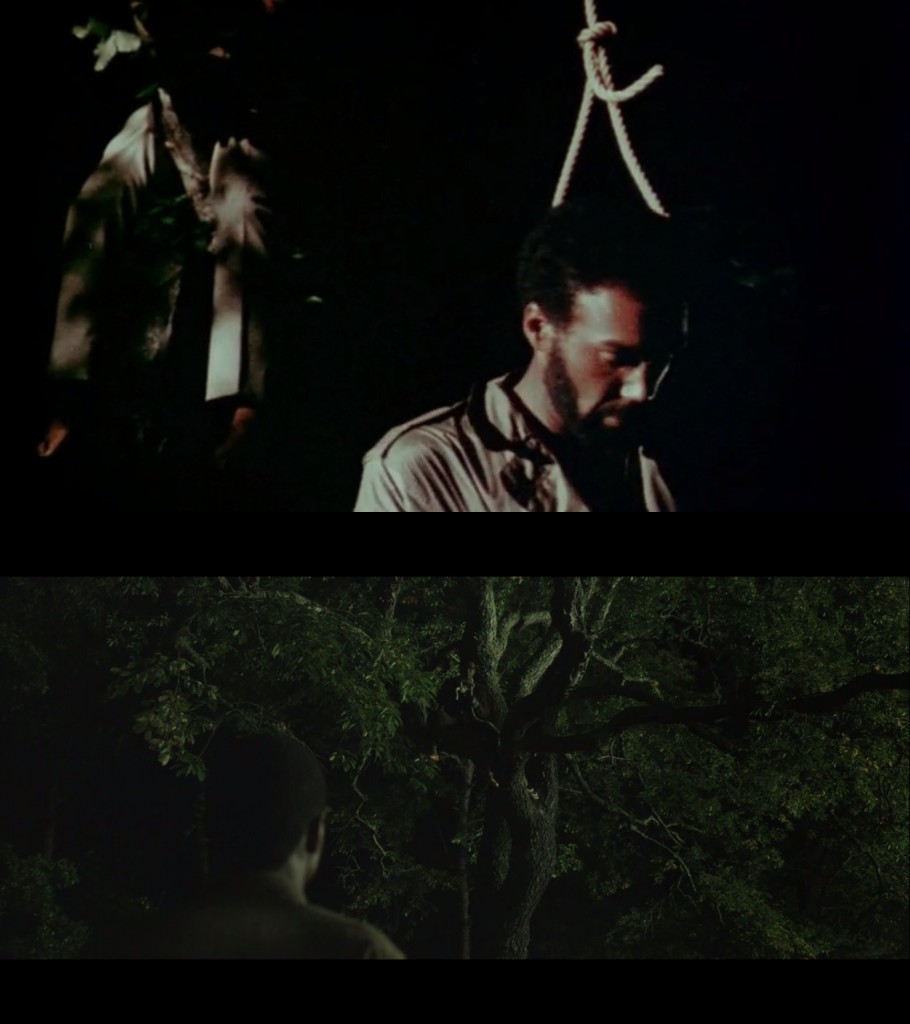

Much of this dichotomy comes from the casting. Stephen Tyrone Williams and Elvis Nolasco (as Hess and Lafayette, the Meda character), despite being fine performers, deliver distracting, actorly performances that make the proceedings ring false and strange. In the original, Jones and Gunn presented very natural, very unadorned line readings and humanistic facial expressions. The absurd nature of the film’s genre trappings are taken at face value because the people you’re watching feel honest and true. The artifice inherent in Williams and Nolasco’s respective takes are on display heavily in the scene where Hess discovers Lafayette drunk and wailing in a tree outside his house.

Even with its budgetary limitations and the coarseness of the film print transfer, Ganja & Hess manages stirring compositions.

In the original, Gunn stages the scene to play out in one continuous take, framing the noose Meda has fashioned in such a way as to loom over Hess. Meda’s disembodied voice off screen, coupled with the childlike dangling of his legs, creates an air of discomfort that hits home how mentally unwell he is without resorting to histrionics. Lee chooses to cover the scene in shot-reverse shot, from this wide of Lafayette in the tree to close-ups of Hess when he speaks. By cutting back and forth between the men’s faces in the center of the frame, a spatial kinship is created which, coupled with the beautiful night photography, makes for a solid scene, but it lacks the peculiar power of the original, largely because it highlights the unnecessary theatricality of Nolasco’s approximation of mental illness. He comes off as a walking plot point waiting to happen rather than an active participant in the narrative.

(I wish I had more to say about Zarahh Abrahams turn as Ganja. It fails to come close to Marlene Clark’s work in the original, but her English accent paired with the awful dialogue written for the role create a singularly grating experience whenever she is on screen. She displays a kind of dynamism in her more silent moments, but this film doesn’t let you enjoy them.)

Now, Bill Gunn and Spike Lee are different directors. I wouldn’t expect Spike to go shot for shot on some Gus Van Sant Psycho shit, but the fact that he otherwise adheres so closely to the original’s structure makes his visual digressions more frustrating. I’d be more able to separate the two films and take Da Sweet Blood on its own merits if I felt Lee had tried to make an entirely new film out of the source material, rather than this weird modern cosplay he’s perpetrated.

For instance, both films are bookended by sequences set in church. Bill Gunn shoots Reverend Williams’ congregation with a lively, loose camera that gives those scenes a distinct sense of excitement totally dissimilar to the rest of the film’s relative stoicism. That juxtaposition is key because it helps illustrate the icy shadow Hess lives in, so when he finally gives in and enters the church to begin his own salvation/destruction, there’s a palpable sense of the church’s role in his redemption. Lee shoots his church kinda the way he shoots lots of stuff, with lots of color and some smooth camera movement, but here that’s no different than the rest of the film. There’s no juxtaposition at all. There is, however, one rousing moment when the signature floating dolly shot Lee borrowed from Mean Streets (and has since iconically made his own) in the film’s concluding act, as Hess appears to levitate between the pews, a poetic aura of inevitability underscoring the prelude to his suicide.

Those are the finest moments in Da Sweet Blood, ones where Lee seems to be making his own film and not butchering a reproduction of someone else’s. Spike Lee’s films are always full of a delightful kind of verve that pops off the screen, whether it’s the images he paints or how he chooses to frame them. Despite my general distaste for the film as a whole, Da Sweet Blood does have some strong moments that remind you why you wanted to watch a Spike Lee vampire movie in the first place. The vigorous shock of Hess first waking up from his “death” (expertly replicated later in the film when other characters are “sired”) springs to mind, as does an admittedly small but notable moment when Felicia Pearson (Snoop from The Wire curiously cast as a prostitute) licks blood red lipstick from her teeth.

Framing the waitress in the background mirror to avoid cutting for coverage gives us this gorgeous composition.

There’s no denying that Lee is still a powerful visual stylist with the chops to create memorable pictures, but here, he spends so much time trying to recreate the magic of his predecessor that he fails to commit to any of his own tricks. If you want to see a black film with bloodsucking in it, I would personally recommend Wes Craven’s underrated Vampire In Brooklyn over Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, but if you want to see the original, Ganja & Hess is an incredible, endlessly rewatchable film. It’s currently streaming on Fandor, which is kind of like Netflix for diehard cinephiles. Gunn’s film is easily worth a month of membership on its own.

If you are still curious about Spike’s version, it’s currently available on VOD and has a small theatrical run, if you want to try to get away from your laptop.

If you have any films you would like to see covered in this column, hit us up on Twitter @DeadshirtDotNet and we’ll get them in front of Dom.