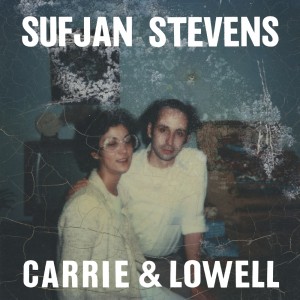

Sufjan Stevens’ new album Carrie & Lowell, his first in five years, is undoubtedly his most nakedly honest release to date. In the past, Stevens has alluded to a lot of the familial issues he grew up with, but they were always couched in metaphors and symbolism in the form of places, famous people, history. His most well-known work, 2005’s Illinois, was an ambitiously sprawling ode to the titular state, but also clearly a personal statement, even if what the statement happened to be was a little unclear. On Illinois, Stevens obliquely wrestles with his dysfunctional personal life, his sexuality, and his nuanced relationship with God. The record’s most honest moments are usually saved for emotional gut-punches, as on “John Wayne Gacy, Jr” when he admits that “On my best behavior / I am really just like him / Look beneath the floorboards / For the secrets I have hid,” or “Casimir Pulaski Day,” when he softly mourns, with his voice cracking, that God “takes / And he takes / And he takes.” But these moments of clarity are sparse, as in that album Sufjan seems to be more comfortable alluding to misery than addressing it head on; after all, it takes an extra measure of courage to air your deep-seated issues in such a public forum, even considering the cathartic release art can bring. In Stevens’ new-found candor though, both on wax and in recent interviews, he has perhaps unwittingly put into the world a codex with which to decipher the covert ways he’s exorcised his demons through his art in the past.

It turns out the key to Sufjan’s emotional turmoil (and therefore the impetus for his art) is his mother, and the substantial impact her presence and absence has had on his life. Carrie, a charismatic enigma who suffered from depression, schizophrenia, and addiction, abandoned Sufjan and his family in Michigan when he was just a year old. He only saw her intermittently during his life, most often during the five years she was remarried to his stepfather Lowell Brams in Oregon. (Brams, who heads Stevens’ Asthmatic Kitty record label, appears as an instrumentalist on the album.) After they split up, she was something of a vagrant, drifting in and out of his life until she passed away from stomach cancer in 2012. Though he was able to say goodbye to her shortly before her death, Stevens realized that her passing meant that there was no chance for him to ever get close to her the way he had always wanted. “Her death was so devastating to me because of the vacancy within me. I was trying to gather as much as I could of her, in my mind, my memory, my recollections, but I have nothing,” he said in a recent interview. “It felt unsolvable. There is definitely a deep regret and grief and anger. I went through all the stages of bereavement.”

All of those stages are on full display within the eleven tracks on Carrie & Lowell—Stevens sings openly about depression, regret, suicidal thoughts, anger, loneliness, intimacy issues, and grace. The ghost of his mother hangs heavily over the album, and much of the subject matter directly addresses either Carrie or the things she did. “And now I want to be near you / Since I was old enough to speak I’ve said it with alarm” he tells her on “Eugene,” but of course it’s too late for that. Elsewhere, Sufjan returns to the other complex relationship in his life, demanding answers from “God of Elijah,” saying “my prayer has always been love / What did I do to deserve this now?” At his bleakest, Stevens isn’t sure he needs to know the answer, asking “Do I care if I survive this?” in “The Only Thing.” He does manage to imbue the album with a sense of hope from time to time, however; losing his mother for good may have torn him apart, but he’s figuring out how to put himself back together. “When I was three / Three, maybe four / She left us at that video store” he sings on “Should Have Known Better,” before the song switches into a sunny, major key and he acknowledges that “My brother had a daughter / The beauty that she brings, illumination.” It’s a golden sunbeam breaking through the storm clouds, a light at the end of the tunnel.

One of the most striking things about Carrie & Lowell is how much of a stylistic left turn it is, especially on the heels of electronic freak-out The Age of Adz. While Stevens’ last few albums have been busy, cluttered with lush instrumentation and sometimes bordering on manic, this LP is the musical equivalent of a Rothko painting—elegant and deceptively simple in execution; yet, the more it is contemplated, the more it reveals itself to the listener. The template for each of the songs on the album is the same: gentle finger-picked guitar and half-whispered vocals, simple chord structures, and the ambient hum of the air conditioner in the Brooklyn studio apartment where he recorded the bulk of the tracks. But at a certain point in each tune, the music blooms to reveal a twist of some sort. Whether it’s the percussive synth in “Should Have Known Better,” the haunting electric guitar line in “All of Me Wants All of You,” or the hazy keyboard and string outro of “Drawn to the Blood,” Stevens’ delicate arrangements allow the songs to organically crack open and let surprising and occasionally heartrending soundscapes bleed through. Every time the gorgeous vocal harmonies lilt “fuck me, I’m falling apart” in album highlight “No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross,” I get a huge lump in my throat.

Frankly, I have no hesitations whatsoever when I say that Carrie & Lowell is a stone-cold masterpiece and easily Sufjan Stevens’ best and most mature work to date. His incredible skill with melody, arrangement, and song structure is as apparent as it ever was, but the masterful economy of sound and crushing emotional gravitas elevate Sufjan to the pantheon of singer/songwriter greats. Comparisons to Elliot Smith are inevitable, though Stevens wallows in misery less; rather, Stevens sifts through his misery in search of grace and reconciliation. Carrie & Lowell is heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, and exhausting, but as always, Sufjan manages to temper it with just the right amount of hope. It’s a dramatic tension that represents his mother as best he knew her: equal parts frustrating and inspiring, cruel and kind. “[She] reminds me of what some people have observed about my work and my manic contradiction of aesthetics: deep sorrow mixed with something provocative, playful, frantic,” he told Pitchfork. “We blame our parents for a lot of shit, for better and for worse, but it’s symbiotic. Parenthood is a profound sacrifice.” Carrie may not have always been there for Sufjan, but in her own way, she managed to give him a great gift all the same.

Carrie & Lowell is currently available in stores, digitally, or through the label’s website.