Everyone has an album that has stayed with them for years, even decades, a constant musical companion that grows with you as your life and perspective changes. With that in mind, Deadshirt presents Perfect Records, an ongoing series of personal essays about the albums that stuck with us and how they’ve shaped our lives.

The last time I was on ecstasy, I was pregnant without knowing it. This occurred several years ago, during a Mountain Goats concert on my old college campus. That sort of music (the kind that always makes me cry, even during extended periods of sobriety and emotional detachment) is clearly not ideal for most sorts of drug use, but I’d bought a gram of really pure stuff from a friend earlier that day and always had trouble saving substances for later use in more appropriate venues. I parachuted the whole thing with a swig from my flask and made my way to the front of the crowd. I would miscarry a few months later, realizing only then that I had anything growing inside of me, but that’s another story.

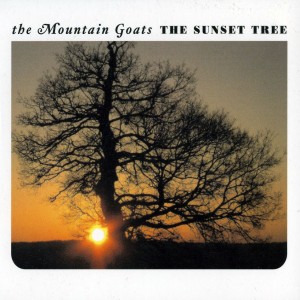

The Mountain Goats have meant something to me since high school, when my first real boyfriend first put on The Sunset Tree during a drive to Taco Bell. Even with its melodic pop sensibilities, the music voiced the extreme stress of enduring life in a fucked up household. I could relate to the frank discussion of domestic abuse; I’d been locked in rooms with my mother during her rage blackouts, and my father’s depression made me witness to some of the swiftest eviscerations of character, between both of my parents, that I’ve ever heard. When I was sixteen, the stress led me to attempt suicide using my migraine medication; I woke up in bed, encrusted with my own vomit, and no one ever noticed. I showered, dressed, then put “This Year” from The Sunset Tree on my iPod and walked to school. As a teenager, John Darnielle’s lyrics consistently reified my prima facie broken heart while leaving me with the language I’d later use to turn the wound into more of a scar. At twenty-three, I considered myself far enough past my childhood and adolescence, and far enough into being a regular drug user, that I could probably handle the synthetic expansion of my figurative heart while seeing a band that elicits such a visceral reaction from me. I ended up lying on a table in an academic building, calling a former partner to pick me up and take me somewhere safe and far away from my feelings.

That brings me to “Dance Music”, my favorite track off of The Sunset Tree. This song, like most of the album, focuses on Darnielle’s childhood spent navigating his status as collateral damage of the abusive relationship between his mother and stepfather. He relies on music to escape the negative intensity of his situation (“Leaning close to my little record player on the floor / So this is what the volume knob’s for”) from an early age, and ends the song as a teenager, listening to the same sort of music while having a nervous breakdown over a partner leaving him at the end of their complicated relationship. The band sets the entire song to, appropriately, a pleasant and almost lulling dance beat that lyrics like “There’s only one place this road ever ends up / And I don’t wanna die alone” flow over paradoxically. The fear of abandonment expressed by someone so young, along with the repetitiveness of the melody, reminds me of my most neurotic and cyclical thoughts and builds a sense of pressure usually not felt outside of noise music.

The rest of the album contains shades of every sentiment expressed in this particular song. “Up the Wolves” constitutes a shockingly realistic assessment of the wasteland surrounding the peace some people need to find for themselves (“There’ll always be a few things / Maybe several things / That you’re gonna find really difficult to forgive”), while “Love Love Love” layers Darnielle’s boyish voice (despite the fact that he was in his late thirties at the time of the album’s release) over even softer music while he sings about foolish, earnest expressions of different kinds of love. The concept of love looms large over the album as a whole, even when it constitutes negative space in songs like “Dialudid,” in which a full set of strings backs lyrics describing opiate-fueled, teenage lust (“If we live to see the other side of this / I will remember your kiss / So do it with your mouth open / And take your foot off of the brake / For Christ’s sake”). The lyrics to “Hast Thou Considered the Tetrapod” almost lovingly describe a simultaneously enraged and tortured parent (“You are sleeping off your demons / When I come home”) beating a teenager (“I am young and I am good”), juxtaposing the image of Darnielle protecting himself with the indication that the only thing he cares about is music. However, the best parts of the album consist of its smaller moments, like the repeated phrase “at last” on the sign-off song “Pale Green Things,” and the way Darnielle sings the word “Scotch” during the course of the teenage anthem “This Year”. These instances almost anthropomorphize the music itself by affecting a sense of internal breakage.

I love the composition of The Mountain Goats’ songs because they temper ostensible folk pop melodies with a repetitiveness that stops just short of droning. Where the lyrics illustrate the rich internal life of their narrator and, occasionally, those around him, the absence of instrumental spectacle and the presence of such a consistent beat provide a technically consistent muscle flexed by the complex emotions expressed within Darnielle’s stream-of-consciousness verses. In the spirit of their favored song structure, The Mountain Goats also rarely use refrains, at least on The Sunset Tree. After all, they’re really just telling stories that build to a catharsis that the narrator has difficulty finding. This album is a bildungsroman about growing up during a sort of emotive Great Compression, and its style reflects that. There’s a break somewhere in certain lives that is terrifying, whose disparate parts no amount of knowledge can hew into a comforting narrative again. At that point, all time spreads itself between the mind and the distance from it, and the individual walks from house to house, begging for the joy of an end by their own hand, rather than mere survival amidst the vague cacophony of the history comprising them. Or, you can, you know, do what Darnielle does: Muddle through it and, most importantly, talk about it to someone.

Now, I’m settling into adulthood better than I ever thought I would. I lift weights and am training to fight in MMA matches. Writing more consistently makes me no longer unleash the beast on others, as I did during college. The process of apologizing to the people I’ve hurt still feels like a lifelong project, but I live in less fear of becoming a victim-turned-abuser than I once did. Bad things still happen to me, but nothing is ever going to feel as bad as the place I’m coming from. I spent most of the last few years internalizing positive things about myself and the larger world that I only understood intellectually before. Feeling is compulsory, but expression is radical. It’s the progression from saying you love someone to cupping their face in your hands that turns a person into a human. When you struggle with mental health issues and a complicated past, you have to be that someone to yourself.

The liner notes of The Sunset Tree read:

“Made possible by my stepfather, Mike Noonan (1940-2004): may the peace which eluded you in life be yours now.

Dedicated to any young men and women anywhere who live with people who abuse them, with the following good news:

you are going to make it out of there alive

you will live to tell your story

never lose hope”

The Mountain Goats are the first people, and the only men, who ever made me unafraid to discuss my experiences, and unashamed to have had them in the first place. Theirs will always be my dance music.