Comic books have long been considered a male-dominated industry, though they in fact have a rich and diverse history of female writers and artists. Our own Kayleigh Hearn will examine the works of female comic creators in superhero comics, indie favorites, manga, and any undiscovered gems or oddities that come her way, in her monthly column Ink Ladies.

One of the best recurring gags in Noelle Stevenson’s Nimona happens on the second page: Ballister Blackheart, villain extraordinaire, dismisses Nimona as a potential sidekick because she’s a kid. “I’m not a kid,” she huffs, then demonstrates her remarkable shapeshifting abilities. “I’m a shark!” Nimona’s shark form, complete with two legs, ridiculous breasts, and pointy grin, becomes something of an in-joke between the sidekick and her mentor, but the scene also encapsulates the comic in a handful of panels. People underestimate Nimona because of her appearance—she’s young, and a girl—but what do appearances mean to a shapeshifter? With her unlimited shapeshifting abilities, and an origin shrouded in mysteries and lies, Nimona is far more dangerous than she seems. Like Grover, she is both our main character and the monster at the end of this book.

Nimona originally began as a webcomic; now completed and collected in a hardcover book published by HarperCollins, it’s the kind of comic that will have the words “subversive” and “metatextual” thrown at it a lot. (The first three chapters are still available to read on Stevenson’s website.) The comic takes place in a fantasy world that is just familiar enough so that readers are surprised by the liberties Stevenson takes. This isn’t the first book to combine science and sorcery, but the medieval-futuristic world of Nimona, full of knights and jousting, but also zombie movies and mad scientists’ laboratories, is a fun literary mash-up. (It’s also blessedly, mercifully, steampunk-free.) Nothing in Nimona is what it appears to be at first glance.

The world Nimona inhabits is run by the Institution of Law Enforcement and Heroics. Despite the presence of a king, the Institution seemingly runs everything—even villain Ballister Blackheart answers their calls. Encased in a dark suit of armor and possessing a devilish, pointy beard, Lord Blackheart certainly looks the part of a villain. He has the reputation of a villain, too—Nimona spontaneously appears in his lair and offers her skills as his sidekick, proclaiming she is a “huge fan” of his work. But despite Blackheart’s cynical worldview and a career of dastardly deeds, he doesn’t really feel like a villain. He operates under his own set of rules, the most important of which is “no killing,” a rule Nimona petulantly scoffs at. (When Nimona takes the form of a little girl and stabs an unsuspecting guard in the back, it’s like a child disobeying daddy.)

Blackheart was going to be a hero, once. He trained at the Institution to become a hero, until a jousting match with his good friend (and, it is implied, lover) Ambrosius Goldenloin left him maimed and unsuitable for the Institution’s needs. It’s a classic supervillain origin story—”I was going to have everything, until that fool Richards Goldenloin ruined me!”—but Stevenson cleverly turns readers’ expectations on their heads. Blackheart has a damn good reason to be bitter, and the explanation for who, or what, is at fault for the jousting accident is more complex than it appears. The Institution needs heroes and villains, and if Blackheart cannot be a hero, he’s forced to become a villain. But with a name like Lord Blackheart, maybe he never had a chance.

But Nimona isn’t so simplistic as to say, “Lord Blackheart is really the hero of the story, and Goldenloin is really the villain;” rather, both men are shown to be more complex than their grandiose names and labels would have you believe. Possessing a flowing gold mane and willowy good looks, Goldenloin isn’t a bad guy, really, but he’s too good to be true. He’s grown complacent as a hero, and at first turns his head away from the Institution’s misdeeds, but he’s also a lonely soul who misses the man he loves. I first found Noelle Stevenson’s art years ago through her humorous X-Men: First Class fanart on Tumblr, and it’s hard not to see distant echoes of Magneto, Professor X, and Mystique in Nimona’s central trio of best friends turned enemies and a shapeshifting girl.

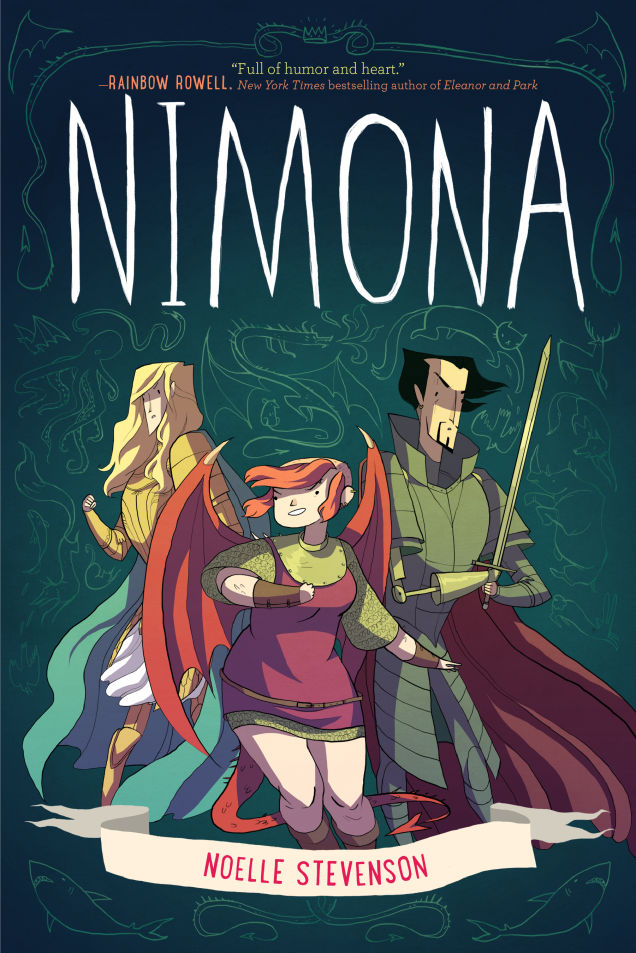

If Blackheart and Goldenloin represent a confused but rigid system of order, Nimona is a chaotic whirlwind that knocks them all down. She’s introduced trespassing in Blackheart’s lair, and from that first panel she looks like someone who doesn’t quite belong where she is. With a stocky build and a head of punkish pink, partially-shaved hair, Nimona is an immediately unique presence—I can’t think of anyone in comics who looks quite like her. Stevenson is an adept character designer, and draws Nimona with a rounder, deceptively softer appearance than the tall, pointy, practically jagged people around her. Of course, being a shapeshifter, she could choose to look like everyone else, but Nimona stands out even before she sprouts wings or a pair of cartoonishly-huge Hulk arms.

The HarperCollins release of Nimona begins with a unique dedication: “To all the monster girls.” Nimona is not a nice girl. She’s funny, spunky, clever, and wild, but she is also a liar and a murderer. (And really, who wants to be nice when Nimona makes being bad look so much fun?) She’s a “monster girl” in form and deed, though whether she is a girl disguised as a monster or, as Ambrosius insists, a monster disguised as a girl, is best left to the reader to decide. Notably, the comic is completely free of the usual female archetypes that inhabit fantasy fiction. Besides Nimona, the most prominent female characters are a scientist and the Institution’s Director. There are no princesses, elf maidens, nor wenches to be found, and the only witch in the story is revealed to be a fantasy. Nimona is a satisfying book if you’re looking for female characters who are different, who are something else—difficult girls, angry girls, girls who don’t want to be controlled (or, if this were a different comic, girls who are non-compliant). The comic features sharp, incisive characterization that is all the more impressive for a creator’s first series, with believable characters who are more than archetypes.

SPOILERS AHEAD:

Nimona and Blackheart form a surprisingly deep, familial relationship over the course of the book, and while they come to understand and influence each other in interesting ways, the story is thankfully not about a good man redeeming a bad girl. Nimona’s final transformation is both tragic and terrifying: the wacky sidekick has become the dragon. The monster girl must be defeated, not only to save innocent townspeople, but to also finally restore Blackheart and Goldenloin’s friendship and, ultimately, give Nimona’s tortured psyche a measure of peace. Perhaps my biggest qualm with the book overall is that Nimona’s biggest crimes are glossed over very quickly. Early on, Blackheart warns Nimona that “If you’re going to kill someone, you’d better be sure. You’d better be prepared to accept responsibility.” Nimona’s final rampage ends the corruptive rule of the Institution, but her innocent victims are mourned in a vigil that lasts all of a single panel. Does Nimona accept responsibility for these deaths? Perhaps if the comic dwelled on it too long, readers would lose sympathy for Nimona right when she needs it most. Stevenson ends the book with an epilogue full of ambiguous hope, rather than strict moralizing. Everyone can change—not always for the better, but sometimes they do. Nimona is a book full of slippery, shapeshifting identities: Blackheart is more than a villain, Goldenloin is not quite a hero, and Nimona is more than a sidekick. Of course, girls can be anything—even a monster.