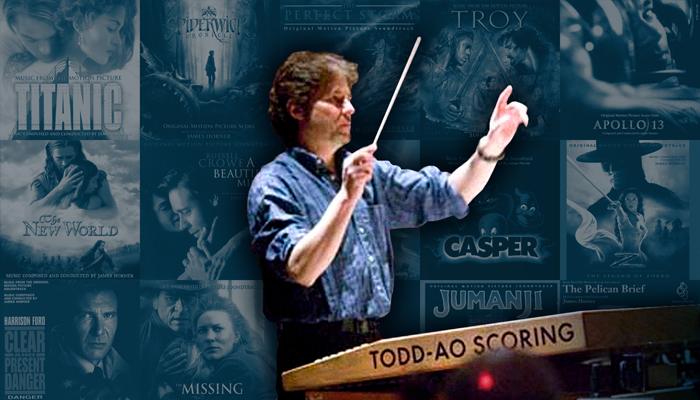

Oscar-winning composer James Horner’s sudden, tragic passing last night at the age of 61 affected me in ways I wasn’t expecting. Horner, who died in a single-plane crash in California, was a solid film composer for 35 years, but in the age of John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith and a host of other definitive names in soundtrack lore, his malleable style was easy to overlook.

When I thought hard about it, though, there are four major points to be made about the quality and longevity of Horner’s work. With the soundtrack industry typically ass-backwards in its approach to digital music, making a traditional playlist difficult, here’s a recap of what made Horner one of the unsung greats of the genre.

Themes of Wonder

For a number of reasons, likely his younger age or his approach to scoring (which we’ll get into in a few paragraphs), James Horner wasn’t given the same kind of top-line recognition that Williams, Goldsmith, or even Zimmer have enjoyed in the past three or four decades. Of the ten Oscars for which he was nominated, he only won two, both for the behemoth Titanic in 1997.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NlzkGd7qaMY&w=560&h=315]

But his gift for writing music that could fill you with awe, inspire you to believe in surmounting odds, or just plain pump you up was relatively boundless. His taut score to Aliens in 1986 was composed in four days, less than six weeks before the film was released; despite the rush job, at least one cue, “Bishop’s Countdown,” has become a mainstay of film trailers. 1988’s Willow is one of the most underrated scores of the decade, offering perfect swashbuckling themes for its pseudo-Lord of the Rings vibe; Horner and director Ron Howard collaborated on another beauty, Apollo 13, in 1995.

For my money, though, it’s the two scores to the An American Tail films that really represent the breadth of Horner’s skills. Part ethnomusical adventure scores, with rousing themes inspired by the locations (impoverished Russia, late-19th century New York, the Old West), and part Disney-esque musical (“Somewhere Out There” being its chief song export, but more on that in a bit), the scores to An American Tail and Fievel Goes West (the first film I ever saw in a theater) remain unspeakably important in the annals of film score history. Of particular note is the sequel film’s end-title theme, Linda Ronstadt’s “Dreams to Dream,” subtly built around a throwaway motif at the end of the first film.)

Boldly Going Where Few Have Gone Before

To the surprise of nobody who’s ever clicked on this website, Star Trek is kind of a big deal around these parts. James Horner is a crucial part of the franchise’s musical makeup.

Alexander Courage set the tone with the The Original Series’ wistful, adventurous theme in 1966; in 1979, Jerry Goldsmith took Trek music into warp drive with the stirring theme to Star Trek: The Motion Picture (later repurposed as the title theme to Star Trek: The Next Generation). However, it was Horner’s score to 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan that really put both series and composer on the map. Horner’s filmography had six titles, two of which were low-budget Roger Corman titles, when Paramount Pictures and director Nicholas Meyer plucked him from the herd to score Khan. At the time, Trek was a considerable cult franchise, not a tentpole juggernaut. (Horner was in fact partially picked due to a reduced budget after the middling performance of The Motion Picture.)

But Horner’s embrace of the film’s tonal direction—less a Star Wars-esque romantic epic, more a Horatio Hornblower in space—offered a fresh musical perspective on what even casual filmgoers would call one of Star Trek’s finest moments. Today, The Wrath of Khan, as well as Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, remain high watermarks not only in Trek lore, but in sci-fi score history.

Musical Education

Perhaps this is respect for the deceased, but one of James Horner’s greatest criticisms can, in a certain light, be regarded as one of his secret strengths.

Throughout his filmography, there are significant examples of the composer subtly appropriating existing classical works for the screen. His works in the Star Trek film series quote Prokofiev; elsewhere similarities have been detected between Robert Schumann’s Rhenish Symphony and the theme to Willow. The most notable to my ears are the main title to Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, very similar to the Looney Tunes mainstay “Powerhouse” by Raymond Scott, and the training sequence in An American Tail: Fievel Goes West, which sounds painfully close to Aaron Copland’s Rodeo.

That said, hearing these pieces and connecting them to other works is not necessarily work to be done in a classroom. In this sense, for some, Horner may have been an unwitting teacher of themes and styles that came centuries before, opening minds to music they weren’t going to hear on the radio.

A Crossover Hitmaker

Speaking of radio, James Horner’s most underappreciated skill was his ability to, more than any of his contemporaries, create music that was heard often outside the confines of the silver screen.

In the Golden Age of film composition, it was not uncommon to see composers find success on the Billboard Hot 100. Henry Mancini was a perfect example: If his own themes weren’t going gold, like the sultry motif of The Pink Panther, they were becoming standards in the hands of vocalists, like Andy Williams’ immortal take on “Moon River.”

Once the pendulum swung first toward a more pop-oriented musical approach in Hollywood (around the release of The Graduate) and then back toward a classic orchestra sound (when John Williams started winning Oscars for Jaws and Star Wars), no composer—not Williams, not Goldsmith—really nailed the crossover theme on the charts except Horner.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXOE6EQtKcU&w=420&h=315]

When Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil set lyrics to “Somewhere Out There” from An American Tail, sung by Linda Ronstadt and James Ingram, it peaked at No. 2 and took home a Grammy for Song of the Year. Two years later, Diana Ross hit No. 11 in the U.K. with “If We Hold On Together,” the beautiful theme to The Land Before Time. And, of course, Horner and lyricist Will Jennings struck multiplatinum with “My Heart Will Go On,” Celine Dion’s inescapable theme to Titanic, a No. 1 hit in eighteen countries and winner of an Oscar, a Golden Globe, and Grammy Awards for Record and Song of the Year. It’s ultimately a rare kind of winning streak that will likely never be topped.

Perhaps it was Leonard McCoy’s eulogy for Spock at the end of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan that says it best about Horner’s enduring film score legacy: “He’s not really dead. As long as we remember him.”