Comic books have long been considered a male-dominated industry, though they in fact have a rich and diverse history of female writers and artists. Our own Kayleigh Hearn will examine the works of female comic creators in superhero comics, indie favorites, manga, and any undiscovered gems or oddities that come her way, in her monthly column Ink Ladies.

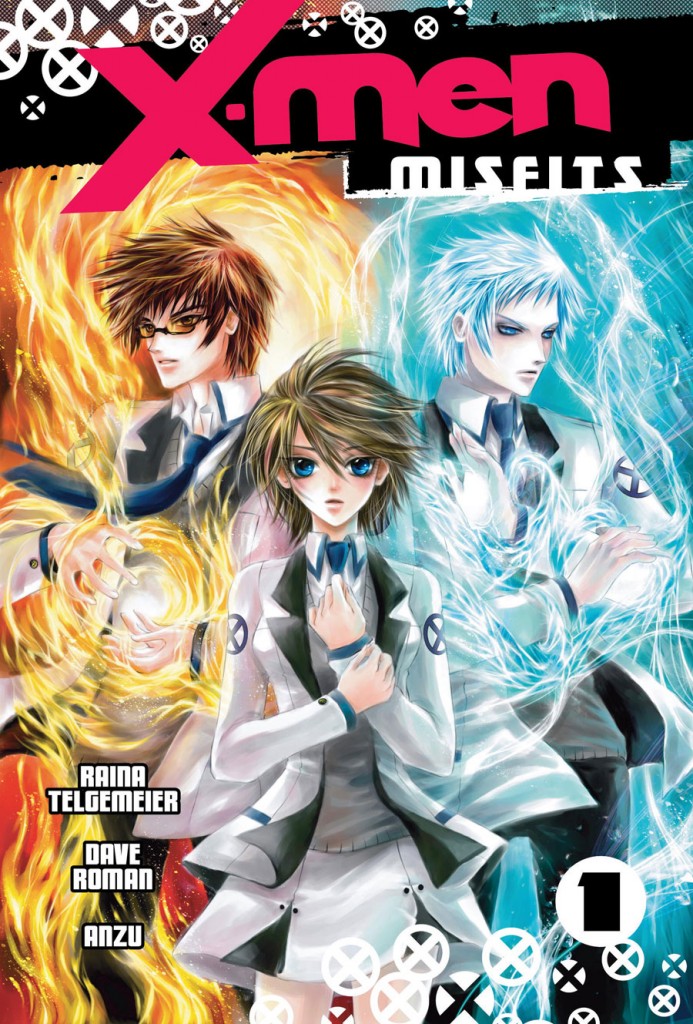

An inexperienced, wide-eyed teenage girl goes to a mysterious new school, where she and her misfit classmates uncover mysteries, marvels, true love, and their own hidden powers. I could be describing a countless number of young adult novels or shojo manga titles, but I’m also describing the life of Kitty Pryde, whose arrival at the Xavier Institute for Gifted Youngsters at the end of Uncanny X-Men #138 marked a dramatic new direction for the superhero comic. Published by Marvel and Del Rey in 2009, X-Men: Misfits was a more recent attempt at re-imagining the X-Men with Kitty Pryde as its idealistic heroine—but with the world of the X-Men re-envisioned as a shojo manga fantasy full of sparkles, teen angst, and impossibly beautiful bishonen. X-Men: Misfits was cancelled after one volume, and it has been understandably written off as one of Marvel’s unsuccessful attempts to hook manga readers, but it’s notable for being the only X-Men book co-written by young adult comics superstar Raina Telgemeier. There isn’t an X-Men comic that looks quite like Misfits, for all the good and bad that implies—X-Men: Misfits was riddled with cliches, and yet strangely filled with promise.

Written by Telgemeier and her husband Dave Roman with art by Anzu, X-Men: Misfits begins with fifteen-year-old Kitty Pryde (sporting a short, tomboyish haircut that’s a dramatic contrast to her usual comics appearance) being recruited to the Xavier Institute for Gifted Youngsters by Magneto. Of course, since this is a young adult book titled Misfits, Kitty feels awkward and out of place among her sisters and classmates even before she tells the reader that she can walk through walls. Kitty is immediately impressed by the Xavier Institute, but is soon shocked to learn that she is the only female student. (“You’re the first female student to enroll at Xavier’s Academy in years,” Iceman tells her, and a reason why—Legacy Virus? Emma Frost’s rival school for girls?—is never given.) Kitty finds herself living an adolescent girl’s fantasy, surrounded by an entire student body of gorgeous mutant guys (including Angel, Multiple Man, Gambit, and Quicksilver) all vying for her attention.

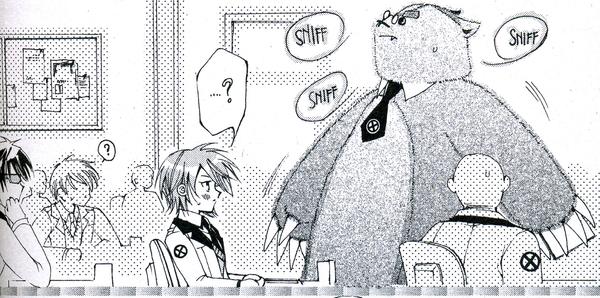

The first half of the book focuses on Kitty adjusting to her bizarre new school, and for a while there’s some pretty fun stuff. Telgemeier and Roman present a Kitty Pryde who is plucky, but also a bit shy and awkward, and wears a bike helmet and pads in her room in case she suddenly phases through the floor. She’s not the snarky ninja techno genius comics fans have become used to, but she’s not far off from Claremont and Byrne’s original conception of the character. X-Men: Misfits is a good example of why Kitty Pryde has endured as one of the X-Men’s most popular characters, often acting as an audience surrogate. When we see the X-Men through her eyes, it’s genuinely fun and exciting. Misfits breaks freely from comics canon—something I’m sure plenty of message board denizens scoffed at—but it leads to some cute new character interpretations, like Beast as a Totoro-esque ball of fluff in a tie and pince-nez, or Colossus with an adorable iron cap and mustache. Fred Dukes/Blob is introduced as Kitty’s good-natured friend, a welcome departure from his usual “fat guys are evil and dumb” characterization. The best character re-introduction has to go to teen Cyclops, a pissy vegan who rejects Kitty’s offer of cheesepuffs and shows off his straight edge tattoo. There have been a million jokes about Cyclops being an uptight killjoy, and Telgemeier and Roman made it feel fresh in a single scene. You definitely knew a kid like Cyclops in high school.

(If you’re thinking, “Okay, where the hell’s shojo Wolverine?” I have bad news: he’s conspicuously absent, as if the hirsute, cigar-chomping killer mutant would rather blink out of existence than get a shojo manga makeover.)

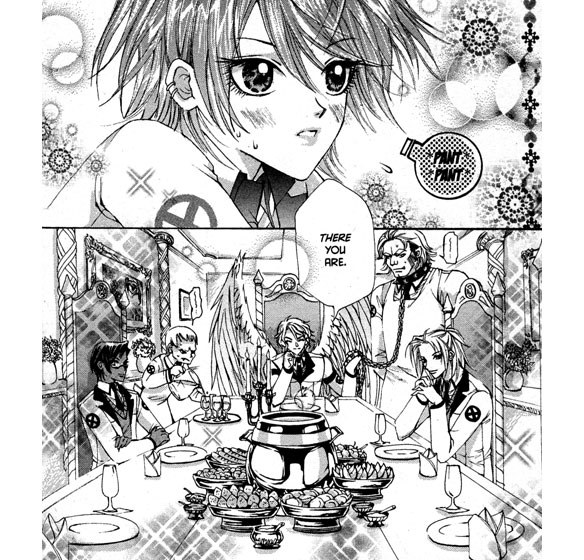

Possibly the most bizarre part of X-Men: Misfits is its version of The Hellfire Club, now a clique of the school’s richest, prettiest boys. The Hellfire Club chapters owe a huge debt to shojo manga titles like Fruits Basket and Ouran High School Host Club, wherein a young heroine is taken in by a group of bishonen who can be labeled as easily as boy band members: The Hot One, The Rich One, The Geeky One, etc. Indonesian artist Anzu has clearly studied her shojo manga (the feathers! the screentones! the hearts!), but while characters like Beast and punk professor Storm have a unique sense of fun to them, her character designs for the Hellfire Club are stiff and generic, with characters as wildly different as Angel, Forge, and Quicksilver sharing the same willowy body types, spiky haircuts, and pointy chins. (I even kept confusing Pyro and Cyclops, because both had dark hair and glasses.) But, by some strange paradox, as generic as their looks are, the more bizarre the plot gets whenever they appear. Forge sounds a literal trumpet when Angel makes his entrance. Sabertooth serves the Hellfire boys dinner while wearing a spiked collar and chain that Angel holds—and it is never explained. Every scene with the Hellfire Club is a strange slice of madness, and I wanted more.

X-Men: Misfits is ultimately dragged down by an unconvincing love triangle between Kitty, Pyro, and Iceman. Kitty’s trapped between fire and ice—look at the three of them posing on the cover!—and it’s all very dramatic, very shojo, and very boring. Pyro is the predictably hotheaded “bad boy” of the Hellfire Club. Kitty begins dating him, but his temper soon makes it obvious he isn’t boyfriend material. Unfortunately, he’s not even a consistently written bad boy. In one scene he tells Kitty to “lighten up” after she objects to Havok’s unwanted advances, but a few pages later flies into “Marky Mark in Fear” mode and threatens Blob just for sitting next to Kitty on the bus.

But if Pyro is clearly the wrong guy for Kitty, Iceman isn’t any better. Bobby Drake gets possibly the biggest personality transplant of all the characters in X-Men: Misfits. Gone is playful class clown, replaced by an icy, sullen loner who freezes out Kitty whenever she talks to him. Yep, the characterization is that on-the-nose. Even after a dramatic confrontation at the end of the book, it’s unclear why Kitty should date either of them. Perhaps in the planned second volume Kitty would have successfully thawed out his heart, but as it stands his characterization is very one note. Of course, re-reading the book in 2015, Bobby being the one boy at school seemingly disinterested in Kitty Pryde reads much differently now, in a way that Telgemeier and Roman could never have intended. Perhaps it’s telling that Telgemeier’s most popular books focus on younger, middle school-aged characters and avoid traditional love triangles. X-Men: Misfits works best when it’s about a girl awkwardly trying to fit in at her new school; when it leaves that setting and sticks to the most rigid shojo manga tropes—like the love triangle—it becomes so insubstantial it might as well phase through the floor like Kitty.

Originally planned as a two-volume series, X-Men: Misfits reached the New York Times Graphic Book Bestseller List in 2009, but the first volume was deemed not profitable enough to continue. (Another Del Rey/Marvel “manga,” Wolverine: Prodigal Son, was also axed after a single volume.) The history of Original English Language (OEL) manga, and questions regarding artistry and authenticity, are too complicated to go into here—suffice it to say that while the book’s back cover calls X-Men: Misfits a “Del Rey Manga Original,” not a page of it was created in Japan. Ultimately, the book was a failed attempt at bridging the gap between (young, female) manga readers and comic book fans, which was a worthy goal. With the X-Men’s reliance on fantastic powers and soap opera dramatics, the leap to shojo manga isn’t an impossible one. Despite its unevenness, I get the impression that the creative team had a real emotional involvement with the book, rather than regarding it as a cynical franchise cash-in. I do wonder a bit about the canceled second volume, how the story would have concluded, and whether that ending would have fixed the weaknesses in plot and characterization. (If nothing else, the second volume promised more female characters, and an X-Men universe without characters like Jean Grey, Mystique, Rogue, and Emma Frost feels strangely empty.) I saw Raina Telgemeier at SPX in 2013; when asked about Misfits, she acknowledged the project with gracious regret. Luckily Telgemeier bounced back from Misfits’ cancellation—the following year Scholastic published her graphic memoir Smile, which along with its sequel Sisters, would become a critically acclaimed bestseller. X-Men: Misfits brought some interesting twists to Marvel’s mutants (vegan Cyclops!) and featured a likeable heroine, but its reliance on shojo manga cliches held it back from greatness. A one-volume oddity among the X-Books, X-Men: Misfits is itself a misfit.

Come back next month for another installment of Ink Ladies!