Film is an entertainment medium that, by its very nature, tends to reward the viewer in rewatch. Sometimes movies even reveal to us how we’ve grown or changed since we last saw them. Our own Max Robinson reassesses old favorites, seasonal classics and the occasional oddball lost under the couch in his monthly column, Stale Popcorn.

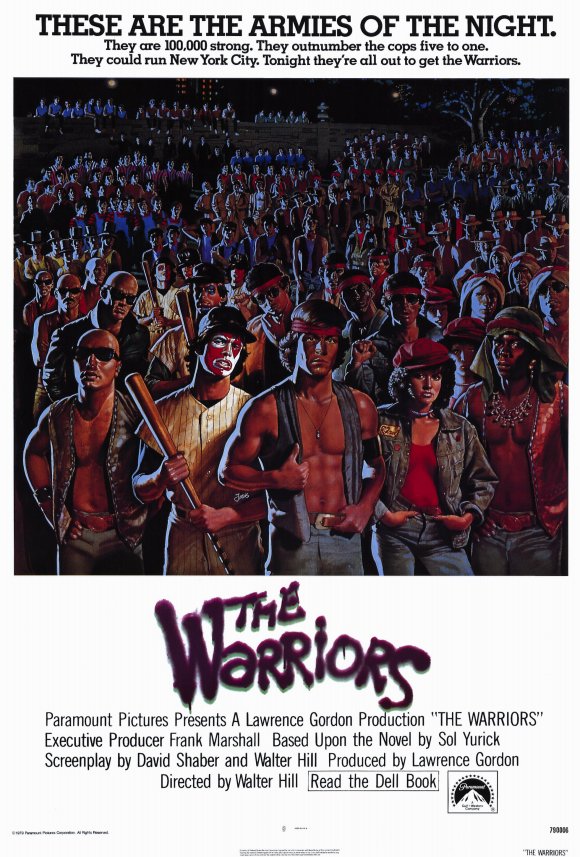

As we bid goodbye to Summer and hello to Fall (and Halloween. And horror movies.), I felt like it was an appropriate time to revisit a movie I mentally associate with the dying days of the season: The Warriors. Walter Hill’s 1979 film is a fascinating artifact in the HD light of 2015; a now 36-year-old movie intended to reflect a not-so-distant future New York wallowing in stagnancy, on the verge of collapse. The world of the film exists in a hypothetical time period that never came to be. The Warriors is a movie characterized by dogged desperation that’s seen in how our heroes sweatily run, hide, and fight for almost its entire run time.

The plot of The Warriors, loosely based on Xenophon’s Anabasis, couldn’t be more straightforward. The various youth gangs of New York have gathered in The Bronx to hear a speech from charismatic crime-prophet Cyrus (Roger Hill), who proposes to unite the 60,000 strong gang population in a revolt against the 20,000 or so police attempting to hold NYC together. Cyrus is assassinated by an audience member, who frames a member of Coney Island-based Warriors. The film takes place over the course of one night, as The Warriors “bop” their way back home against impossible odds.

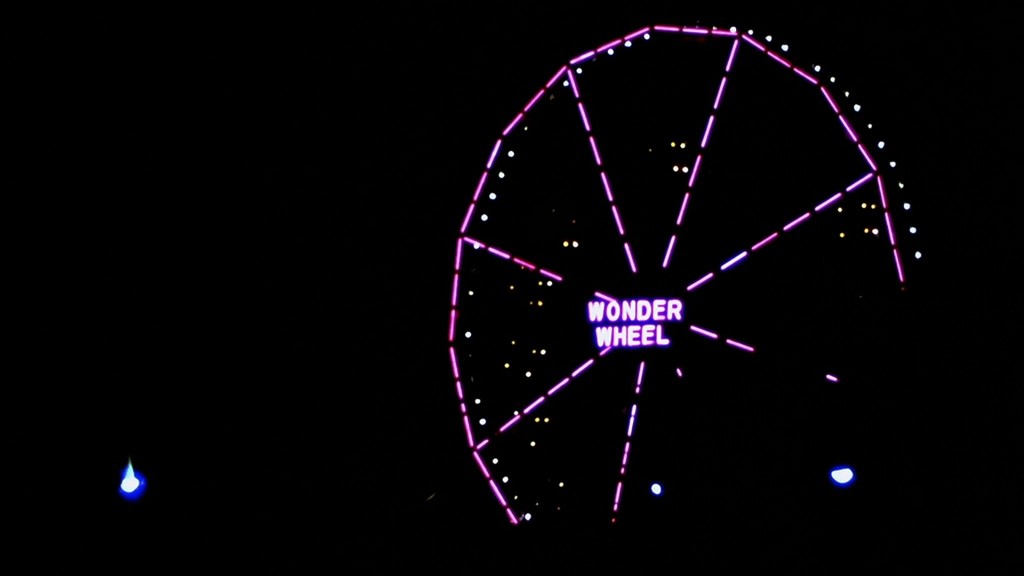

One thing I really admire about The Warriors is how it’s a New York movie that shows amazing restraint in its choice of locations. There are no sweeping helicopter shots of the World Trade Center or Brooklyn Bridge; we don’t see Rockefeller Center or the Statue of Liberty. The film’s penultimate fight scene doesn’t take place in Times Square; it’s in Union Square. Instead, the film limits itself to opening and closing on Coney Island’s iconic Wonder Wheel. The shots of the Wonder Wheel are decidedly unromantic, first tilting emptily in the darkness at the film’s start. When our heroes make it back home, we see it unmoving and unlit in the early dawn like a piece of construction equipment rather than an amusement park attraction. The Warriors‘ Manhattan is all side streets, damp underpasses, and nearly vacant subway stations, a perfect portrait of the city as it appeared in the late Seventies. The youthful delinquents of The Warriors exist in a kind of twilight urban underworld, the New York that exists just out of the corner of your eye on a late July night.

There’s a sense of profound sadness and loss that pervades The Warriors. At first, we might think that the film is going to revolve around Cyrus and his war on armed authority. When Cyrus is shot by the psychotic Luther, there’s a surreal slowness to his literal fall from grace. Cyrus could have been the next Caesar or Alexander The Great, the salvation of the disaffected kids that make up New York’s gangs. Cyrus’s promised crime utopia is the promise of a better life, gone in the flash of a gun barrel. A few of the Warriors can only mourn for what could have been for a few seconds before they have to run.

We see more of this hopelessness in the romantic interactions between Warriors leader/”war chief” Swan (Michael Beck) and female hanger-on Mercy (Deborah Van Valkenburgh). When Swann cruelly criticizes Mercy for her willingness to sleep in a new bed every night, she exhaustedly tells him that “This is the life I got left, know what I mean?” The disenfranchised youth of The Warriors don’t have happy lives to look forward to, only poverty or jail time if they’re lucky. “This is what we fought all night to get back to?” Swan remarks bitterly as the gang walks through a closed Luna Park.

For all its comic book, B-movie bluster, The Warriors‘ best scene is a quiet moment between Swan, Mercy, and two couples coming back from prom on a late night subway train. The laughing couples—in high white disco collars and nice dresses—quiet down once in the midst of the filthy, intimidating gang members. The camera lingers on the high schoolers’ scared expressions, Swan’s dirty fingernails, and finally an abandoned boutonniere. In a moment of rare warmth, Swan picks up the flower and hands it to Mercy, not wanting something so nice to go to waste. Pretty, nice things are a luxury not afforded to people like Swan and Mercy.

The Warriors‘ major non-atmospheric strengths are a handful of great performances. Roger Hill’s Cyrus appears in the film for only a few moments, but his sermon atop a crude wooden platform is unsurprisingly the most memorable part. His fire and brimstone “Caaaaan youuuu diiiiig ittttt?” is iconic for a reason. Hill makes us care just enough about Cyrus, potential savior or snake oil salesman, before his death.

The Warriors themselves are fairly rote save for James Remar’s Ajax, a vile shitkicker whose aggression is barely tolerated by his fellow gang members. Ajax is the kind of monster created to thrive in the lawless violence of this New York, and Remar plays him like a conquering barbarian. Handcuffed and beaten after attempting to rape an undercover police officer, our last shot of Ajax is Remar’s quivering, bloodied face looking up against flashing siren lights. David Patrick Kelly, as Luther, plays the film’s villain with a kind of psychopathic glee. The leader of the non-descript Rogues, Luther just wants to hurt people however he can. His justification for murdering Cyrus and framing The Warriors? “No reason, I just like doing that kind of stuff.” Luther is a great movie crazy in a decade of cinema with no shortage of those.

Despite the film’s kind of bummer tone, The Warriors allows its heroes what we can assume is an all too brief happy ending. As the members who made it home walk along the surf against Joe Walsh’s “In The City,” we’re left to wonder how many of them will live to see 30.

Check out more Stale Popcorn by Max Robinson.