It’s October. With Halloween hot on our heels, we thought it appropriate to take a look at legendary horror author Stephen King’s best, worst, and strangest translations from page to screen. Baby, can you dig your man?

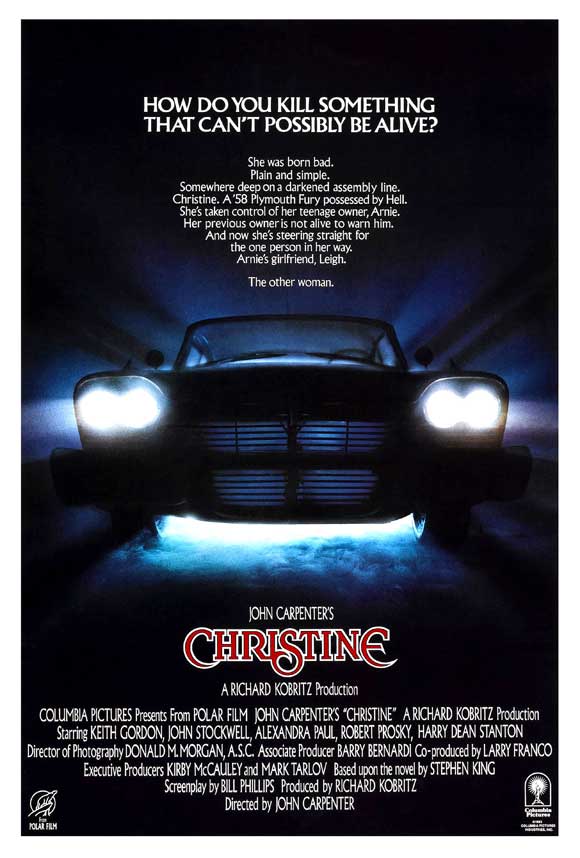

On paper, John Carpenter taking on the film adaptation of Stephen King’s Christine looks like combining chocolate and peanut butter. It’s a slasher movie in which the killer is a demonic ’58 Plymouth Fury written by the biggest horror novelist of the 20th century and directed by the guy who pretty much invented the slasher movie, but somehow it lands in the Kimchi Taco realm of acquired taste.

Starting in the mid 1970’s with Assault on Precinct 13 and Carrie, respectively, these two masters of horror kicked off separate decade-long hot streaks of the strongest work of their careers. By 1983, King was essentially printing money every time he poured himself a pint of Robitussin and Wild Turkey to type a few hundred pages about the best highway shortcuts in rural Maine. Carpenter had failed to capture the same level of financial and critical acclaim that his genre-defining masterpiece Halloween had achieved in 1978, but the cultural footprint of Escape from New York (1981) and The Thing (1982) had cemented his place as a singular voice in science fiction and horror with some of his best work still to come.

The basic story of Christine is as classic and shiny as the titular hot rod: bullied geek Arnie (Keith Gordon) purchases a beat-up muscle car from an old man, and as he restores the car it starts turning him into The Fonz, at the cost of alienating his jock best friend Dennis (John Stockwell) and his family. Also, turns out the old man’s ghost lives in the car and splatters anyone who pisses off Arnie or doesn’t use the ashtray. In an ideal world this should be Little Shop of Horrors with chrome details and bucket seats, so why is Carpenter’s Christine iconic despite being sort of a mess?

For starters, there’s the source material. At arguably the peak of his powers, no editor was going to say “No” to Nellie Ruth King’s son, and that is where the trouble starts. Man, Christine is a long damn novel. It’s not just the classic King Americana-Tolkien thing where he describes the history of the route of every mailman in town; it’s the repetition and the spiraling plots about cigarette smuggling that ultimately go nowhere, and the numbing ruminations on what it means to be a teenager and some of the most excisable descriptions of breasts I’ve ever read. Tor’s Grady Hendrix rightly compared it to a story told by a drunk.

There’s no theme or scene in Christine that isn’t done better quicker in some other entry in King’s oeuvre. You want nerd revenge? Read Carrie. You want car-nage? Read “Trucks” (just don’t watch Maximum Overdrive). Christine is a novel about contemporary teenagers that feels completely out of touch with their taste and habits, and whose centerpiece literally is an old man trying to live forever through a car. As a result, the ’50s rock lyrics that head every chapter and Arnie’s transformation into a ghoulish facsimile of Christine’s previous owner seem less like a canny rumination on growing up and the end of teenagerhood and more like a disingenuous nostalgia trip.

The film rights to Christine were sold before the book was even finished, and ultimately that may be the movie’s saving grace, as Carpenter does his best to wrap a soggy hoagie in aluminum foil and crisp it back up in the oven. He started with the important change of making Christine a character rather than a vehicle for the soul of her owner, a seemingly subtle difference that ultimately makes her more mysterious and horrifying. In the first scene below, Carpenter visually establishes so much about the character of Christine that the lack of explanation for her autonomous homicidal tendencies becomes part of her charm.

It’s a credit to both his skill as a storyteller and King’s basic killer car idea that the potential of Christine shines through the adherence to some of the novel’s weaker story beats, namely the jarring middle third where narrator Dennis is in the hospital and our perspective undergoes a strange change from first person to third. John Stockwell’s Dennis makes you wish that they had made Kevin Bacon a slightly better offer for the role, but his all-American charm is sorely missed as Arnie’s descent into madness is left with no sympathetic characters to play off of. With Dennis indisposed for a long stretch, it’s up to the supporting cast to provide counterpoint. While the villainous bullies (including one played by famed Venkman-hater Steven Tash) and suspicious detective (Harry Dean Stanton, bringing it as always) are great, under-drawn love interest Leigh Cabot (Alexandra Paul) is given very little character beyond loving Arnie for reasons unclear and hating Christine because Christine is always trying to murder her.

This shortcoming is addressed by ramping up the romantic element that exists between Arnie and Christine, charging their solitary moments together with a strange intimacy. The lingering shots of Christine border on pornographic and serve to nurture the viewer’s obsession with her, placing her in the audience’s eye as not only a sentient being but the actual object of Arnie’s affections. This has the strange effect of changing the tone of Christine’s personal story arc. It was pointed out to me recently that once Christine is explicitly anthropomorphized by the characters and cinematography, a scene of the bullies destroying her ends up feeling uncomfortably close to a scene of sexual assault, a fact borne out by the score for that section being titled “The Rape.” Somewhere the script falls short of making Christine a relevant metaphor for the relationship between masculinity and car ownership, but the heightened sense of sexual tension in this scene of Christine healing herself borders on the erotic, like body horror for cars.

Carpenter’s touch also turns the precious epigraphs into a source of dramatic tension and black comedy, underlining or undercutting as necessary. I don’t know if we can singlehandedly credit Carpenter as the inventor of “’50s rock played to make a moment creepier,” but he’s definitely a pioneer. A fat guy gets crushed to death while “Bony Moronie” plays. That’s good stuff. That’s cinema.

Carpenter’s pyrrhic victory here, making what he calls his least-favorite of his movies, comes from having constraints that millionaire superstar author Stephen King could have used a few more of. Confined to a movie’s running time and a low budget, Carpenter cut fat with a machete and ultimately found a leaner, meaner Christine than King himself could make, even if it is occasionally saddled with the inherent design flaws of all murderous Plymouths.

Check back all this month for more essays on Stephen King stories on screen.