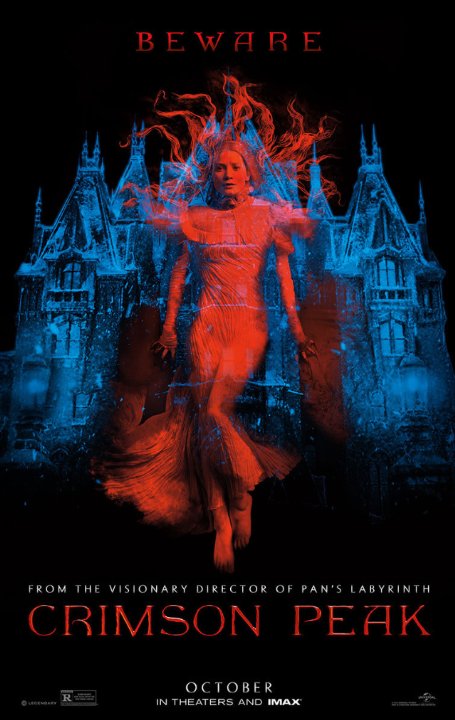

“It’s not a ghost story,” says writer Edith Cushing of her manuscript, early in Crimson Peak. “More a story with ghosts in it.” Through Edith, we can hear director Guillermo del Toro cautioning his audience. Crimson Peak is populated with writhing specters and the occasional burst of violence, but the sumptuous Gothic Romance may not be the horror film you were expecting.

Guillermo del Toro is the kind of filmmaker hailed as a “craftsman” by his fans, and the world of Crimson Peak is as intricately crafted as the clockwork scarab in his debut film, Cronos. Del Toro’s love of classic horror drips over every frame of the film, a hybrid of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, and Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho. (Even the shadowy fingers of Nosferatu and the black-gloved killers of countless Italian giallo films creep into the story.) Adamant that his film should be called a Gothic Romance, del Toro embraces the conventions of the genre rather than subverting them, serving all the classic ingredients on a silver tea tray: a crumbling estate, a strong-willed heroine, a husband with a secret, and many, many ghosts.

(Spoilers below)

Crimson Peak begins with Edith as a child, visited by the ghost of her mother. The ghost warns her, “Beware of Crimson Peak.” Edith grows up into a bookish, independent woman (played by Jane Eyre herself, Mia Wasikowska), beloved by her industrialist father but mocked by others for prioritizing her writing over more “feminine” pursuits, like romance. When a stuffy dowager and her daughter unfavorably compare Edith to “spinster” Jane Austen, Edith replies that she wishes to be Mary Shelley, who died a widow. (Fittingly, Edith Cushing takes her name not only from novelist Edith Wharton–who wrote her share of ghost stories–but also with an actor who played Mary Shelley’s famous doctor for nearly two decades.) Enter Sir Thomas Sharpe (Tom Hiddleston), a penniless baronet desperate to eke out a living as an inventor. Soon Edith is in love, and despite her father’s disapproval and the icy demeanor of Sharpe’s sister, Lucille (superbly played by Jessica Chastain), their marriage is inevitable. Swept away to Sharpe’s ancestral home, Allerdale Hall, Edith finds out it has another name: Crimson Peak. As she begins to understand her mother’s warning, Edith is drawn into a world of both ghostly and fleshbound horror.

The film’s more fantastic moments are anchored by excellent performances. Mia Wasikowska’s Edith is a bright and resourceful heroine, and even in her most imperiled moments she’s never presented as a shrieking, helpless damsel. Dressed in gold and white, the blonde Edith is framed like a ray of light in the shadowy house. Del Toro also has a comfortable grasp on portraying female points of view; the sensual, long-awaited consummation of Edith’s marriage feels tailored to the female gaze. Hiddleston, with his sharp, pale features, looks like the platonic ideal of a Gothic hero, and he imbues Sir Thomas with a brooding sensitivity that never approaches parody. As soon as he picks up Edith’s manuscript and praises it (“Where I come from, ghosts are not to be taken lightly”), it’s understandable why Edith would love him; why, despite her father’s misgivings, she would see him as a kindred, misunderstood soul. It’s the strength of Wasikowska and Hiddleston’s chemistry that makes the events at Allerdale Hall feel like a genuine tragedy, rather than a sentimental girl’s folly.

I hesitate to say more about Jessica Chastain’s Lucille, but Crimson Peak is a film driven by women and their desires: the desire for love and security, for life itself, and even to save a man’s soul. Almost unrecognizable with a coil of black hair at her neck, Chastain’s disdainful exterior hides a torrent of twisted emotions. Cold, controlling, and criminally possessive of her brother, Lucille resents Edith’s presence in Allerdale Hall, and even her most mundane tasks, like making porridge or playing the piano, are filled with menace. When her passions are unleashed, Lucille is as vicious as one of Dracula’s brides, and the conflict between Edith and Lucille is far more intriguing than the ghosts.

Hiddleston and Wasikowska are the perfect embodiment of the Gothic hero and heroine, but the film’s casting stumbles with Charlie Hunnam as Dr. McMichael, an old friend of Edith’s who adds an underwritten love triangle element to the film. Golden and hunky where Thomas Sharpe is dark and skeletal, Hunnam provides an interesting visual contrast to Hiddleston, but it can’t overcome his character’s bland, expositional personality. Hunnam was perfectly suited piloting giant robots and slaying kaijus in del Toro’s Pacific Rim, but in Crimson Peak he’s a human anachronism, and his scenes in the final act feel a bit like cheating.

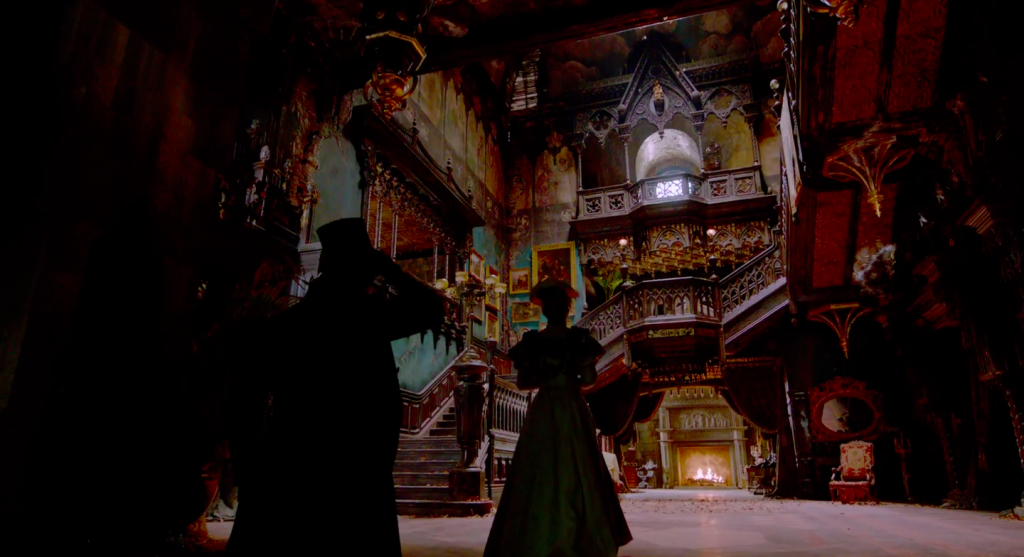

The most vivid character in Crimson Peaks is Allerdale Hall itself, the spiritual successor to the House of Usher and Shirley Jackson’s Hill House. Allerdale Hall is a decaying corpse of an estate. The ceiling is collapsing (falling leaves and snow drift through the hallways, creating scenes of otherwordly beauty), and red clay oozes through the floorboards from the mines below, like the house itself is covered in festering sores. Del Toro is not the first writer or filmmaker to present a haunted house as a kind of creaking, groaning, living thing, but Allerdale Hall still feels like a wholly unique creation. Crimson Peak is a treat for the senses: the chill of the snow, the rattling of a ring of keys, and the pulsating redness of the clay are all amplified by del Toro’s skilled direction, creating a world that is haunting and unreal. The film is worth seeing in IMAX if only to appreciate the full spectacle of the house–every moldy painting, every hallway illuminated by candelabra.

Though Crimson Peak is an achievement in atmosphere and set design, it’s a disappointment that the story is such a weak foundation. Edith is a clever heroine, but the truth she uncovers is predictable and not as shocking as the film needs it to be. Ultimately, the hauntings in Allerdale Hall can be attributed to the oldest motivations in the book: greed and lust. It’s here that Crimson Peak needs to be stronger than its influences; when people think of Hammer Horror or Mario Bava films, they remember style, color, and scares — not the plot. Guillermo del Toro’s film is a sumptuous Gothic Romance; there are scenes here I will be thinking about for a long time. Crimson Peak is a visual triumph, enough so that I can forgive it for also being a triumph of style over substance.

Crimson Peak is now playing.