Film is an entertainment medium that, by its very nature, tends to reward the viewer in rewatch. Sometimes movies even reveal to us how we’ve grown or changed since we last saw them. Our own Max Robinson reassesses old favorites, seasonal classics and the occasional oddball lost under the couch in his monthly column, Stale Popcorn.

For last year’s Halloween-focused Stale Popcorn, I talked about The Fog and the original ‘78 Halloween. I went back and forth on a few choices for this year, but ended up settling on, appropriately enough, Halloween III: Season of the Witch. I find myself fascinated by Halloween III for a couple of reasons. Its place in the Carpenter canon/larger Halloween movie franchise is a very uneasy one: while Carpenter turns director duties over to Tommy Lee Wallace in favor of a co-producer role, he’s still noticeably involved with the film’s score and script. Season of the Witch is a stark contrast to the prior two Halloween installments in that story-wise it has nothing to do with Michael Myers, Laurie Strode, or Haddonfield, Illinois. In fact, in the universe of Halloween III, Halloween is just as much a movie as it is in the real world. But what’s really interesting about Season of the Witch is how it focuses on many of the same themes and ideas of the original film in a completely new, very weird setting.

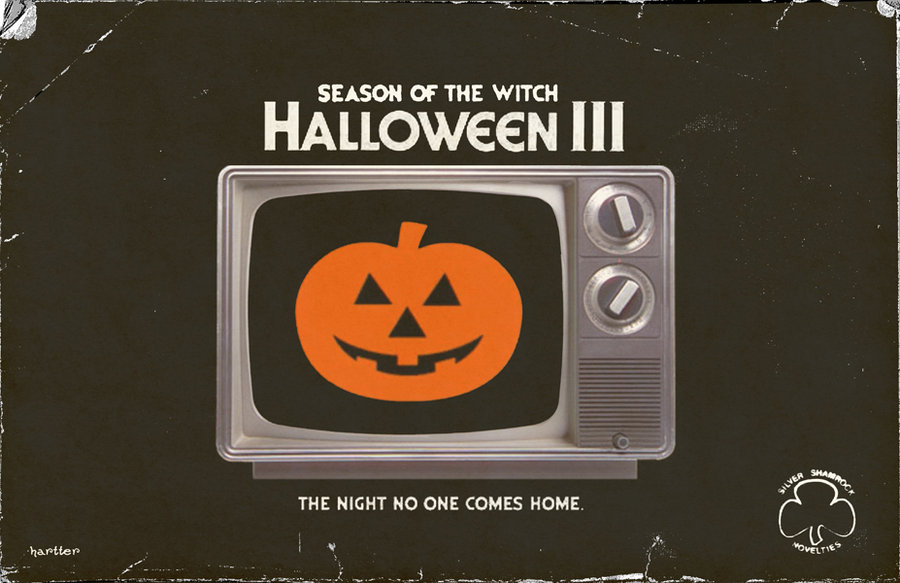

The first major cue Season of the Witch takes from its predecessor is the image of a jack-o’-lantern in the opening credits. Only instead of the flickering physical artifact we’re familiar with, it’s a digital mock up on a television screen, a very specific omen of what’s to come. Almost immediately, there’s a sense of clock-ticking tension at play in Wallace’s film, aided in large part by Carpenter and Alan Howarth’s high-pitched synth score. On-screen text informs us that it’s October 23, 1982 at the opening of Season of the Witch, and as the film progresses, we get closer and closer to the 31st. The movie creeps, inevitably, toward Halloween itself. The movie also subjects us, incessantly, to a commercial for Silver Shamrock Halloween masks, which are evidently the Beanie Babies of the world of the film. The commercial, with its insidiously catchy jingle declaring the number of days left until Halloween, probably plays within Halloween III six times. You get the feeling that you’re being subjected to psychological warfare. Take a look:

Whereas the original Halloween (and its mediocre sequel) were fairly conventional slasher movies, Season of the Witch is anything but. The bizarre, borderline incomprehensible plot follows Dr. Daniel Challis (ur-dad Tom Atkins) as he investigates the foul play death of a hospitalized costume shop owner. Together with the shop owner’s daughter Ellie (Stacey Nelkin), Challis follows a trail all the way to the inexplicable Irish immigrant settlement of Santa Mira, California. Santa Mira happens to be the company town controlled by Silver Shamrock and its CEO, the kindly Conal Cochran (Dan O’Herlihy, probably most recognizable as The Old Man from RoboCop). Halloween III centers around a psuedo-scientific/supernatural conspiracy theory at the highest levels of corporate commerce involving killer Halloween masks, bespoke suited androids, and the partial theft of Stonehenge. Season of the Witch throws the vaguely realistic tone of the prior films out the door and backs over it with its car.

There’s a very distinct flavor to Wallace’s version of Halloween, with a fondness for black humor and a really misanthropic mean streak. This becomes pretty apparent when the contest-winning Kupfer family appears to provide a kind of vague comic relief. The Kupfers, with the father’s ugly sportscoat and disco-pumping RV, are a kind of weird caricature of the American family you’d find in the margins of MAD magazine. This is a movie that gleefully kills a reclining woman with a magic laser fired from a malfunctioning microchip, and goes to great lengths to force our hero to watch as the young Kupfer boy’s head caves in on itself and explodes with bugs and snakes before his parents eyes. When Challis confronts Cochran on his villainous master plan (which is, unambiguously, to kill all of the children watching a Silver Shamrock TV special via microchips containing a piece of Stonehenge), Cochran suggests that it’s all a joke. “The best joke ever, one on the children.” If Carpenter’s original Halloween operated on the stated idea that “everyone’s entitled to one good scare,” Season of the Witch extrapolates the sadism even further.

All of this builds up to a terrific sequence in which Challis, forcibly restrained with a Silver Shamrock mask placed on his head, is forced to watch Halloween as he awaits the inevitable. You have to appreciate a movie that’s arch enough to have a character be tortured by the movie it’s a sequel to. In true body snatcher movie fashion, he’s able to escape and even partially shut off the broadcast, but it’s ambiguous as to whether he succeeds in preventing the Halloween apocalypse.

There’s an undeniable hypnotic, seductive quality to Halloween III underneath the moving parts and abject weirdness. Although it lacks the polish and intelligence of Carpenter’s classic, Season of the Witch appeals to an unconscious darkness within us. The part of ourselves that loves a good scare.

Check out more Stale Popcorn by Max Robinson.