Film is an entertainment medium that, by its very nature, tends to reward the viewer in rewatch. Sometimes movies even reveal to us how we’ve grown or changed since we last saw them. Our own Max Robinson reassesses old favorites, seasonal classics and the occasional oddball lost under the couch in his monthly column, Stale Popcorn.

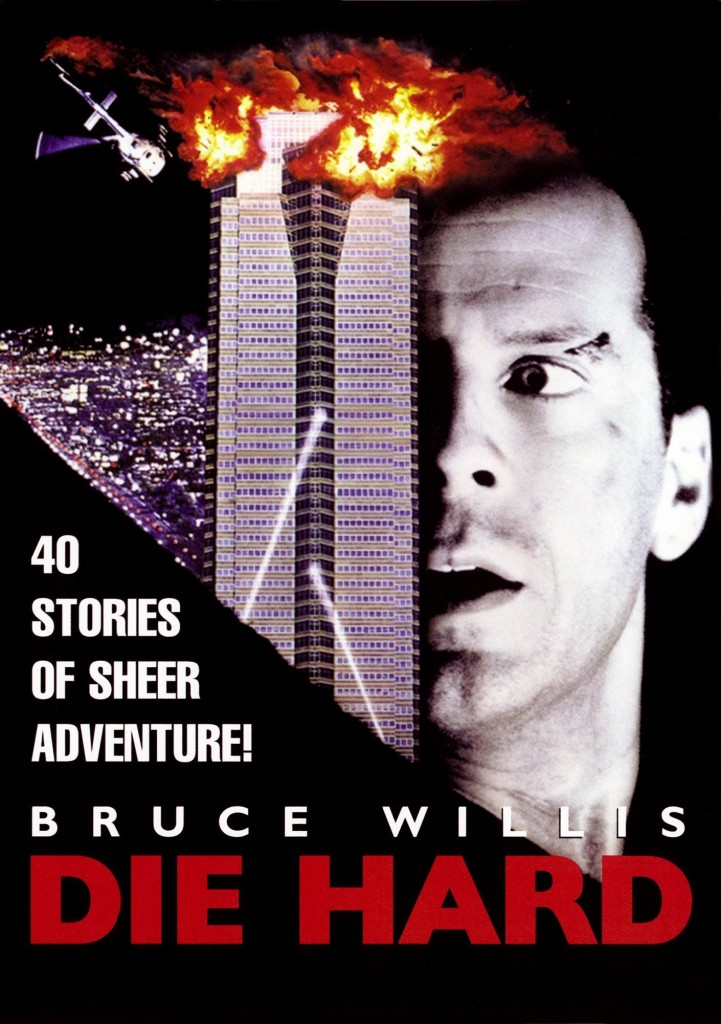

It’s Christmas Eve and I’m holed up in an Amtrak train as I’m writing this, there’s no better time to talk about not just one of my favorite Christmas movies but one of my favorite movies period: Die Hard. I see you cool kids in the back of the class rolling your eyes at me calling McTiernan’s 1988 classic a Christmas flick and, okay, I get it; there are a lot of dummies who ironically claim Die Hard is their favorite Christmas movie with the air of a high school kid turning in his homework half-assed. Your distaste for this cliche is noted and understood. But here’s the thing: I honestly, unabashedly believe Die Hard is a great Christmas movie. But, more importantly, it’s a textbook perfect action film.

Image courtesy of Cut Media.

Let’s talk about how unbelievably fucking good Steven de Souza and Jeb Stuart’s script is. There’s a refreshing efficiency to Die Hard in that within 30 minutes, the movie is completely set up and moving. We’ve met Bruce Willis’ John McClane, we know why he’s in L.A. (wife’s office Christmas party), and we know things between him and the former Mrs. McClane-now-Ms. Gennaro (Bonnie Bedelia) are Not Good. We also know who are bad guys are—Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) and his men—and we even know that Hans isn’t quite who he claims to be. Die Hard is not a movie that wastes time: When Reginald VelJohnson’s wise but semi-bumbling Sgt. Al Powell investigates Nakatomi Plaza’s front lobby on a 911 tip, we don’t have to sit through a scene of Hans Gruber barking orders at his men to silence him. Rather, a shot implying the veiled threat of a man with a rifle barely visible around the corner from Powell is enough to put us on edge.

Die Hard is also a movie where actions, even indirect ones, are shown to have major consequences. John’s unfortunate choice to take off his shoes ends up having long term repercussions. William Atherton’s sleazeball reporter isn’t directly involved with the action inside Nakatomi Plaza, but his decision to put the McClane children on camera is what enables Hans to realize that Holly is John’s wife, putting her in immediate danger.

The film’s impressive structure hinges on a series of strategic lies from our cast of characters. John initially has an advantage over the so-called terrorists because nobody but a handful of people know who he is. Hans frames the hostage situation as a colorful political act when in actuality it’s just a very complicated heist. Later, he runs into John and attempts to pass himself off as an American office worker named “Bill Clay” in order to gain John’s trust. John, using an open air walkie-talkie to correspond with Al on the ground, can’t go by his real name so he asks to be called “Roy” instead. Holly’s relation to John is a secret she closely guards. When John finally confronts Hans and his remaining henchman, he’s able to save the day thanks to a gun he’s discretely taped to his back.

Consider this as well: Die Hard is a rare movie with essentially no wasted characters. Everyone, from scummy cokehead Ellis to Argyle the limo driver to Holly’s pregnant coworker, in some way moves the plot along. When we first meet John McClane, an unnamed fellow airline passenger is the one to suggest that John take off his shoes when he gets to his destination. We know John’s a cop because the man visibly reacts to John’s gun. Holly’s aforementioned pregnant coworker is a major consideration when Holly is setting the terms of the hostages’ captivity with Hans. Holly’s boss, Joseph Takagi, isn’t a guy who is arbitrarily blown away when Hans and his men storm the office Christmas party. As Hans painfully reminds us shortly before Takagi’s execution, he had a full name, he had a career, and he even had children who aren’t going to see him again.

Even Hans’ henchmen gets brief, fleeting flashes of humanity: Al Leong’s unnamed gunman hastily eats a candy bar crouched behind a snack bar, Alexander Gudonov’s Karl mourns his younger brother’s death at McClane’s hands, and even Hans himself makes an offhand reference to a childhood love of building models. When’s the last time an action movie gave you even halfway three-dimensional villains like this?

Even more than great supporting characters, Die Hard has the best action hero lead you could ask for in John McClane. What makes McClane such a terrific character is, unlike say Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando, his appeal lies in his vulnerability. John McClane is pretty quickly established as an asshole, his deteriorating marriage very plainly the result of McClane’s resentment of his wife’s new high-powered career and his own refusal to consider her needs as a spouse. John responds to Holly’s heartfelt “I missed you” by petulantly throwing her decision to go by her maiden name back in her face.

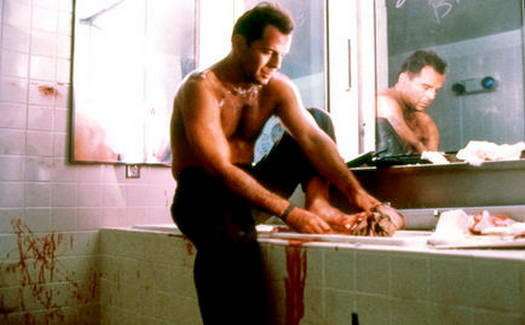

But at the same time, John is an inherently decent person. It’s noteworthy that John’s first kill in the movie—henchman Tony breaks his neck during a staircase fall—is a complete accident. The first time we watch him choose to take a life, it’s a calculated decision in self-defense, and he doesn’t take any pleasure in it. “Next time you have the chance to kill someone, don’t hesitate,” says one of Gruber’s goons, to which John sarcastically replies “Thanks for the advice.” John begs Hans to let a doomed SWAT team fall back during an assault on the building and he even tries in vain to save Ellis when the man foolishly tries to leverage his way out of the hostage situation. John and Al bond not just because they’re both beat cops, but because they both know all too well the pain their guns bring them. As John picks glass shards out of his feet over a bloody bathroom sink, it’s clear we’re faced with a very different breed of action hero than what we’re used to.

Die Hard is a very innovative action film beyond just offering new twists on an established Hollywood formula, too. Michael Kamen’s work here is well thought out and colorful in a way action movie scores just aren’t. Kamen casts “Ode to Joy” as a leitmotif for Hans and his men, a fittingly German piece of classical music. We hear it playing at the party just before they arrive, we hear a deep, muted version of it when Hans is examining the Nakatomi Corporation vault, and when he’s giving his demands. When Hans and computer hacker Theo finally bypass the final lock on the vault, a bold and brassy version of “Ode” plays. It’s even a gag/plot point that Argyle is unaware what’s occurring in the building above him because he’s blaring Stevie Wonder’s “Skeletons” at top volume.

But the question, the reason for the season, remains. How exactly is Die Hard a Christmas movie? There’s the obvious stuff: John and Argyle listen to “Christmas in Hollis” as they head to Nakatomi Plaza, Al Powell sings (off key and with the wrong lyrics) “Let It Snow” as he heads to his squad car with an armful of sweets, and Theo even gives instructions to his fellow thugs to the tune of “T’was The Night Before Chirstmas.” But let’s talk about the less obvious stuff. Kamen specifically evokes Christmas at a few points, from the phonetic echo of “Walking Through A Winter Wonderland” (think “Gone away is the bluebird/here to stay is a new bird”) that’s present in several cues, to the score’s prodigious use of sinister, hollow sleighbells. John McClane doesn’t just write a note on a dead gunman to intimidate Hans and company, he specifically puts a Santa hat on the corpse and writes “HO HO HO” on his sweatshirt. What does John use to tape the all important handgun to his sweating, bleeding back? Wrapping paper tape with “SEASON’S GREETINGS” printed on it.

Christmas imagery and trappings are unextractable from Die Hard, set dressing elements that actively influence the plot and the feel of what we’re watching. The film’s final moments even give us snowfall in L.A. in the form of the stark white paper bearer bonds falling from the sky. Beyond all these deliberate aesthetic choices, Die Hard‘s very last moments? John introducing Al to Holly as all three prepare to leave the worst office Christmas party of all time. Miracle on 34th Street, eat your heart out.

Check out more Stale Popcorn by Max Robinson.