There are a hundred ways to measure what makes a great movie, but nothing speaks more highly about a film than how closely you can read it. In his new feature, Deadshirt Editor-In-Chief Dylan Roth explores one of his favorite films by demonstrating just how much there is to talk about, writing at length about Every Five Minutes of runtime.

THE INCREDIBLES

Written and Directed by Brad Bird

(c) 2004 Disney/Pixar

News of the World (10:12-11:33)

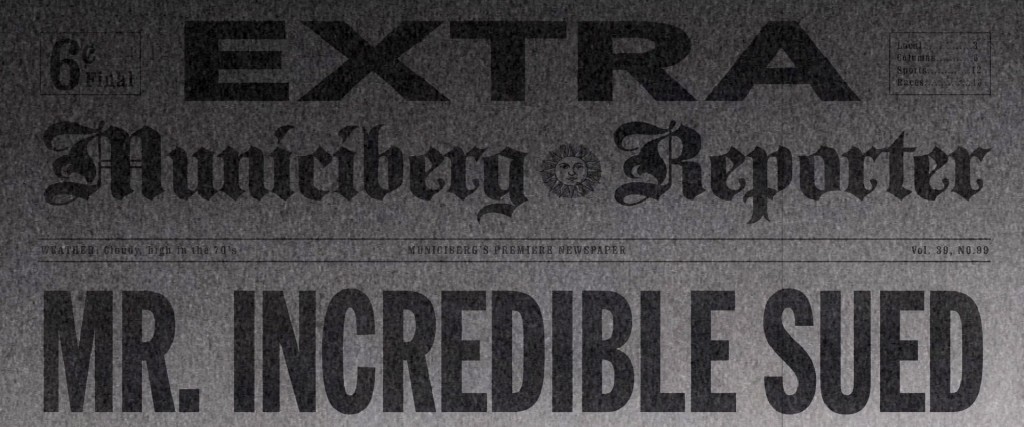

Bob’s rude awakening hits the audience smack in the face, as we smash cut from Bob and Helen’s wedding to a vintage-style newsreel, revealing that, days later, Mr. Incredible becomes the target of a series of lawsuits. First, Oliver Sansweet, the man whose suicide attempt Mr. Incredible so violently interrupted by tackling him through a window, sues him for an injury he suffered during the rescue.

Sansweet’s lawsuit sounds ridiculous, but it’s not totally without precedent. Citizens can sue police officers for damages sustained during an arrest, search, or seizure—police departments are even insured against it, so that officers don’t have to pay out of pocket if they lose. There are limits to this, of course—if the cops knock down your door as part of a legal raid of your home and find evidence of a crime, they’re not obligated to replace your door, but if they turn up with nothing, that’s a different story. The law doesn’t punish people who attempt suicide unless they endanger others, which Sansweet doesn’t seem to do, so he might actually have a case.

Ultimately, it doesn’t even matter if Oliver Sansweet wins his suit against Mr. Incredible—it’s enough to spark an unprecedented deluge of lawsuits against superheroes, who are apparently insured by the US government. It’s not clear how long it takes (this sequence cheats by implying immediacy when it begins but then revealing that time has passed), but before long the burden of these lawsuits becomes too much. The federal government decides that Supers aren’t worth the trouble and puts them out to pasture, agreeing to safeguard their identities in exchange for their immediate retirement from costumed heroics.

The fall of the superhero isn’t the result of a horrible tragedy or a villainous scheme, but of cold, cruel economics.

The concept of the public turning against superheroes wasn’t new when The Incredibles hit theaters in 2004. This is one of a number of plot elements and themes The Incredibles shares with Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ deconstructionist comics opus, which was released in 1986 and ’87 and influenced just about every piece of superhero fiction that followed.

In The Incredibles, superheroes are swept away not because they’re unworthy or irresponsible, but because ordinary people get tired of living in their shadow. They bleed the Supers dry, and then throw them away. It’s funny because it feels true, and yet it doesn’t sacrifice an ounce of what makes the superhero genre work.

The last shot of the newsreel sequence provides our characters’ status quo for most of the film. They’re just like everyone else now, laying low, trying not to stir the pot. They are condemned to a prison of mediocrity, never allowed to make a real difference ever again.

Mr. Insurable (11:34-13:31)

Flash forward fifteen years, a decade and a half since the Supers were forced into hiding, and, first and foremost, the world didn’t end. No supervillain or alien invasion conquered the planet, no extinction-level event went unthwarted. Life has gone on, but it’s missing something—it’s missing color, wonder, and excitement. Mr. Incredible’s world has become our world, a miserable fate indeed.

Bob Parr now works for an insurance company, which is a particularly sick joke. On paper, his job is to help people, but in actuality he’s supposed to avoid helping by any means necessary, finding ways to deny his clients’ claims and maximize company profits. We see Bob at work, where he’s once again confronted with a little old lady in trouble. Where Mr. Incredible would put maximum effort into even the smallest crisis (remember Squeaker?), Bob is now charged with not helping septuagenarian Mrs. Hogensen solve a serious financial problem.

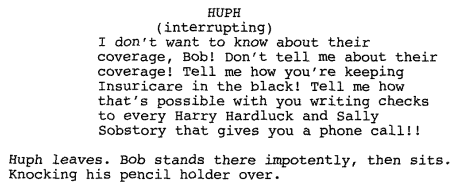

Of course, costume or no, Bob can’t refuse an innocent citizen’s call for help, so he secretly provides Mrs. Hogensen with the exact information she’ll need to circumvent Insuracare’s bureaucracy and get taken care of. This is, evidently, far from the first time he’s pulled this particular stunt, because the moment Ms. Hogensen leaves Bob’s cramped cubicle, in storms his boss, Mr. Huph (voice of Wallace Shawn) to reprimand him for his generosity with company funds.

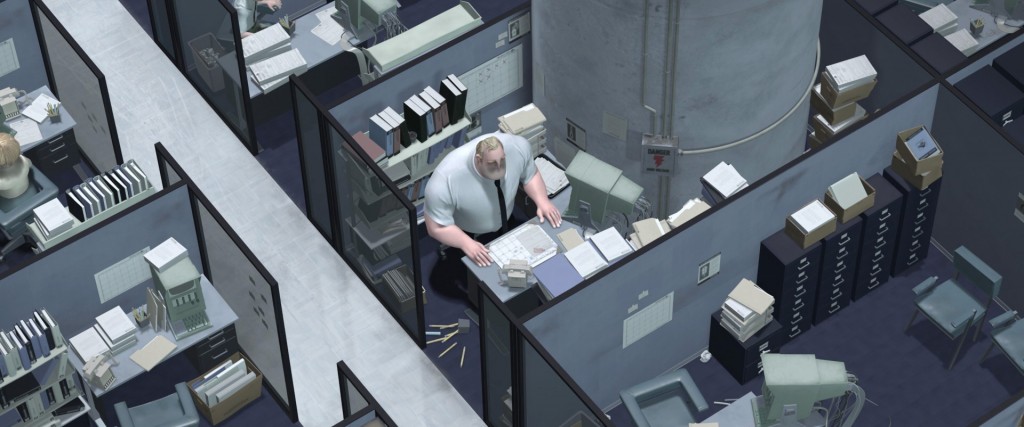

Bob’s new life is comically dreary. His work is contrary to his nature, and we can infer that this is somewhat intentional. The Superhero Relocation Act is designed to hide superheroes, and Bob can’t exactly lay low as a cop or a firefighter—the urge to use his powers would be too great. Here, his strength is useless. While his life as Mr. Incredible was vibrant and fast-paced, his new one is still, gray, and extremely cramped. There’s even a massive pillar taking up half of the space in his already small cubicle. Once he was looked up to with admiring eyes, now he’s getting dressed down by a tiny, villainous bean counter in a bad toupee.

Elastigirl, on the other hand, seems to be doing alright, still finding joy in her life as a suburban mother of three. Where Bob’s office crams him tightly into a sterile white box, Helen is reintroduced in a spacious, warmly-lit house. The color palette isn’t quite as bold and brilliant as back in her superhero days, but it’s calm and homey. Helen is a woman at peace, laughing and joking and goofing off in a cotton blouse instead of a spandex onesie. Bob is a shadow of his former self, but Helen is still the same person she was, more or less.Helen interrupts Bob’s consultation with Mrs. Hogensen with a phone call proudly announcing that after three years, she’s finally unpacked the last of the family’s stuff into the house. As the story unfolds, it’s implied that Bob, Helen, and their kids have been relocated several times before in an effort to keep their identities secret, something that Bob hasn’t made very easy. There’s a reason Helen took her time unpacking: she never knew when they might have to pack back up again. By unpacking that last box, Helen has allowed herself to get truly comfortable. She finally believes they’re done running.

Speaking of running…

Dashiell the Menace (13:32-15:39)

Helen is summoned to the middle school principal’s office, where her son Dash (short for Dashiell) has gotten himself in trouble for the umpteenth time. Dash has his own superpower—superspeed—and like his parents he has to keep his gift a secret. Trouble is, Dash is a bit of a brat, and he has been secretly using his speed to gaslight his teacher, Bernie Kropp. Banned from using his powers to fight crime or compete in sports, Dash has gone the Bart Simpson route and now only uses his powers to annoy. But this time, he nearly gets caught, and it lands his butt in trouble. Luckily, Dash is too fast for even Bernie’s hidden camera to catch, and he gets away with his latest prank while pushing Bernie deeper into cartoonish madness.

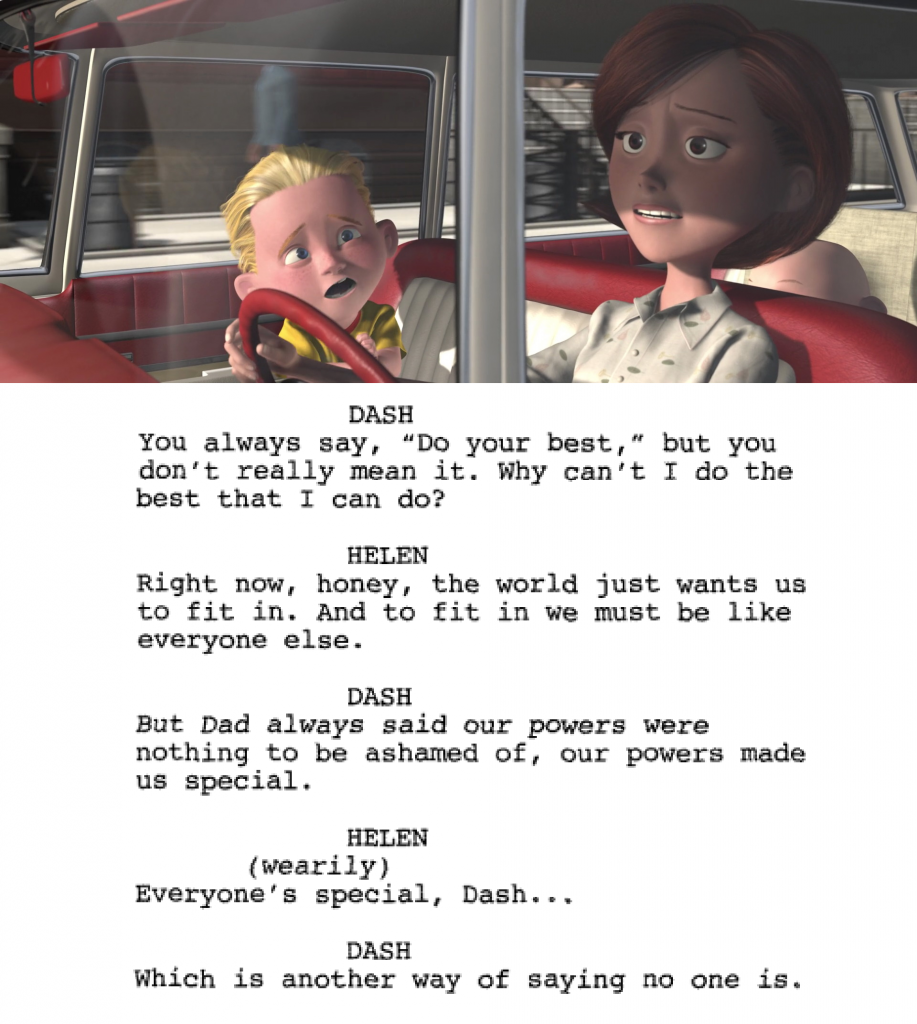

This scene is a fine comedic introduction to Dash, his powers, and his dumb boyish nature, but it’s the following scene between Dash and Helen in private that really sheds light on the both of them. This dialogue is important, so I’m just going to let it roll…

Helen is in a very difficult position. First and foremost, Dash is right—she is telling him not to be the best he can be. Other kids have talents, and ideally their parents nurture those talents to their full potential. Certainly Dash could find other things to be good at apart from running really fast, but the likelihood is that he’ll never be as good at anything as he is at running fast, and neither will anyone else. What Helen is forced to do here is a bit like telling a musical genius that she can’t ever play for anyone because she’d make everyone else look bad by comparison. Of course, it’s more complicated than that—Dash revealing his powers could have disastrous consequences for the entire family—but you can understand why Dash feels betrayed that his mother won’t stand up for him and their kind.

Second, she’s forced to be the bad guy to Bob’s good guy in this argument, even though Bob’s not even in the car with them. Bob gets to be the one to tell Dash that he’s special, while Helen has to play disciplinarian and attract all the resentment. Helen seems to truly believe that hanging up the costumes is what’s best for everyone, while Bob merely tolerates it, so it’s impossible to put up a united front for the kids on this issue. It’s a difference of opinion that nearly derails their marriage, and it’s difficult to resolve because, once again, neither of them is entirely wrong.

Helen’s right—everyone is special. It’s a rote phrase we say to children, but there’s truth in it. No two people are alike and everyone has some spark that makes them who they are. The problem is that everyone gets to be that someone, except Dash, because being himself is too threatening to society.

Dash (and Bob, because I’d bet anything Dash is repeating something he heard his father mutter under his breath at the dinner table) is right too—because at the very least his own mother should think he’s more special than the other kids, instead of trying to convince him otherwise.

The problem is, Helen can’t give Dash the “great power/great responsibility” speech, because that great responsibility has already been stripped from them. Instead, she has to tell him that with great power, they must do nothing. I don’t think this is an easy thing for her to do, but this is the world they live in, and she wants to keep her children safe and anonymous.

Speaking of anonymous, next week we’ll meet the final member of the Parr family, Little Miss Disappear…

Check back next week for another installment of Every Five Minutes: The Incredibles. Screencaps are from DisneyScreencaps.com; the screenplay to The Incredibles can be found here.

![To paraphrase the screenplay, "Motherhood has agreed with [Helen]."](http://deadshirt.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/incredibles-disneyscreencaps.com-1376-1024x427.jpg)