It’s December, a time to reflect on the greatest movies, music, comics, etc. of the last twelve months. And while we try to keep up with the best of everything as they’re released, occasionally something sneaks by us. With the Rest of 2015, we hope to highlight the best materials we missed out on reviewing earlier this year.

So, full disclosure, I am especially predisposed to overthink this movie. I took a course—and loved every minute of it—on religion and science fiction with an ordained minister who presented a paper to Harvard Divinity School on the personhood of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Data. My major paper in that class was on personhood, because I’m an insufferable teacher’s pet when I’m not being an insufferable smartass. As such, I’m a little surprised it took me until this week, the last of 2015, to see Ex Machina.

More Frankenstein than Terminator, Ex Machina is a thoughtful rumination on the distinctions among information, understanding and experience, and how each contributes to what the film calls “consciousness”: sentience, personhood. That said, this is far from a slapdash update of Mary Shelley’s classic. 28 Days Later writer Alex Garland’s directorial debut exhibits a lot of restraint and quiet tension, quite the feat for a man who came to prominence on the backs of zombies who couldn’t be bothered to slow down.

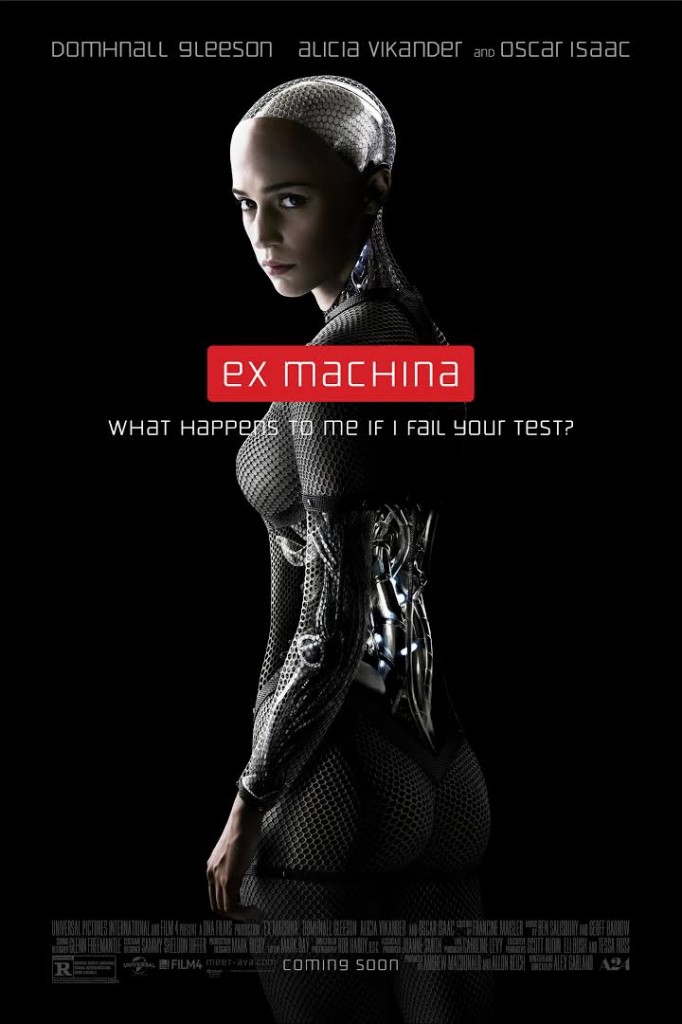

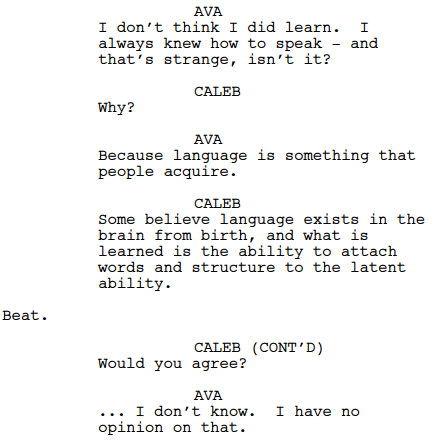

Garland, who also pulled writing duties here, tells a clean, simple story: Young coder Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) is invited by famed programmer Nathan (Oscar Isaac) to Turing test beautiful robot Ava (Alicia Vikander). Ex Machina is the first of two movies starring Gleeson and Isaac that came out this year, the other being a little-known indie release called Star Wars: The Force Awakens. These three principals each turn in excellent performances: Gleeson’s Caleb is eager, fidgety and bright; Isaac’s Nathan is dark and superior while trying so hard to project a sense of ease and warmth; and Vikander’s Ava is otherworldly, reaching for endearing but narrowly stumbling on her way up and out of the Uncanny Valley—in other words, exactly what the part calls for. Early on, Garland presents us with the exchange that, I would argue, is the crux of the film’s thematic oomph:

While this discussion is ostensibly about language—which, it is later revealed, Ava picked up when Nathan The Dark Knight-ed into everyone on the planet’s cellphone to aggregate speech patterns and expressions—what it’s really about is the nature of consciousness, or, in potentially more specific, if less scientific, terms, the soul. Is personhood innate? Is it learned? Can knowledge of it be aggregated, or is empathy, and, by extension, personhood, a product of lived experience?

While these are questions humanity has been pondering in one form or another since long before we were even aware we’re a bundle of nerves trying to pilot a meatsuit while sloshing around in a thoroughly unappetizing soup, they certainly feel more pressing in the modern era. We’re living in an age that generates, aggregates, and analyzes data at a rate that’s so absolutely bonkers that calling it “unprecedented” feels a little like calling Kanye a rapper—you’re not wrong, and there’s nothing bad about that characterization, but you’re not even coming close to touching the scope of what we’re talking about. It’s also an age when self-driving cars created by Google (the clear real-world analog of Ex Machina’s Blue Book) cruise California streets, while perhaps the greatest minds of the last three generations are collectively shaking at the thought of artificial intelligence.

While many works of science fiction (the aforementioned Terminator, for one) stress the unfeeling disconnect from humanity that leads sentient machines to turn on their human masters, and that certainly forms the kernel of Ex Machina’s plot, this is the first story I can recall that works so hard to establish how disconnected from humanity such a machine’s creator would have to be, and it does so in such subtle, believable ways. While there are certainly notes of Shelley’s “modern Prometheus” in Isaac’s Nathan, he’s still more Zuckerberg than Frankenstein, and that’s why Ex Machina works so well. We can see the reclusive billionaire tech genius working on a top-secret advanced technology in his well-guarded, remote compound, because that stuff happens. We can also see him [highlight for spoiler] leveraging someone’s search history to manipulate them, because companies have been selling our search histories to target us with advertisements and study our behavior for years .

While the words “in his image” are never uttered, it becomes clear in the final moments, as [highlight for spoiler]lAva is revealed to have inherited Nathan’s false, manipulative, selfish nature, that she was, in fact, made in her creator’s image. Ex Machina, in addition to exploring the boundaries of personhood, is a considered critique, both of the things we want from our technologies and the behaviors we accept – and expect – from our technologists.

That said, in a movie rife with references to J. Robert Oppenheimer, the reluctant (but far from absentee) father of the atomic bomb, I was a little surprised at how un-cataclysmic Ava is. I do love the final shot, wherein [highlight for spoiler] Ava finally gets what she wants, to be at a crowded intersection where she can people watch, only to quietly panic and hurry away once she gets there. However, if Ex Machina had played out like Terminator or I, Robot or any typical machine-uprising fare, it would have undercut its thoroughly interesting exploration of the technologist’s role in the fast-approaching future. In many whose-side-is-this-AI-on stories, the robots’ creators are cogs in the machine of destiny (read: the plot), frequently killed off-screen and rarely part of the main conflict. Ex Machina stands apart by placing its AI-creator front and center, daring to ask, not how humanity can be saved from robots, but what the origin and role of empathy and humanity are as we are increasingly quantified, sorted, stored and sold—and, perhaps sooner than we think, simulated.