Quick, think about the movie Independence Day.

Now I don’t care whether you hate this movie or love it, some iconic image popped into your head just now. The saucers eerily hanging above cities. The Empire State Building being obliterated from the top down. F-18s scrambling into the air. Firing the nuke into the mothership’s hangar bay.

Independence Day burns itself into your head. Particularly if you were of a somewhat tender age twenty years ago like myself. It recombined the plot of War of the Worlds, the imagery and ensemble of the disaster movie, and the excitement of Star Wars, with just a dash of Arthur C. Clarke’s surreal wonder and H.P. Lovecraft’s creepiness. It was the end of one era—the time when visual effects relied on model work and trick photography much more than on animation—and the beginning of another—prototyping the Bruckheimer/Bay style of spectacle- and emotion-driven blockbuster. We’re all a bit embarrassed of Independence Day because we can’t ignore it.

Twenty years later, director Roland Emmerich and producer Dean Devlin bring us Independence Day: Resurgence. Ironically, it has the opposite problem as its predecessor. It’s a fairly thoughtful extension of concepts and themes brought up by the original. However, it completely fails to replicate the pulse-pounding energy that made the first film such a ride. It banks on your nostalgia while failing to understand why that nostalgia exists. There is no iconic image and no compelled emotional response.

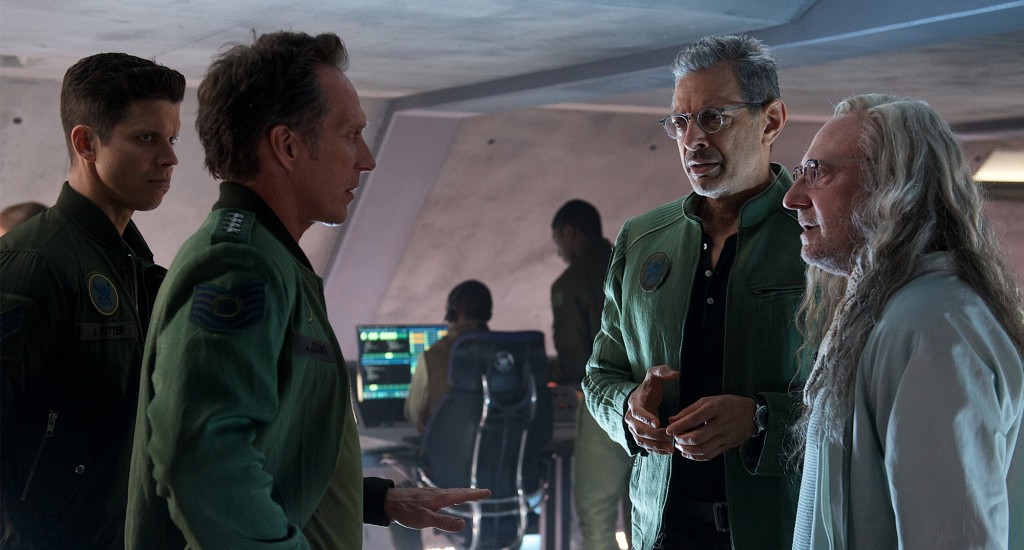

The first act is a pretty fascinating exercise in world building. We get to see who’s still alive (Bill Pullman’s President Whitmore, Jeff Goldblum’s David Levinson, and surprisingly Brent Spiner’s Dr. Okun), who’s not (Will Smith’s Steven Hiller, haunting the proceedings through various photographs), and who’s all growed up (Jessie Usher’s Dylan Dubrow-Hiller, Maika Monroe’s Patricia Whitmore). Earth is a post-alien paradise—just as much of the science fiction of the ‘50s and ‘60s predicted, particularly that of director Ishiro Honda, the existence of an undeniable extraterrestrial enemy has led to the overnight obsolescence of human war. Alien technology has led to practical interplanetary travel and those little hovering ships that are in every movie because they’re easier to animate than real helicopters. Liam Hemsworth, essentially reprising his role as Gale from The Hunger Games, gripes about how boring it is to fly an awesome spaceship that builds kickass laser guns on the Moon. An absolute trainload of other characters get introduced at this point, most of which get formulaic meet-cutes with other characters so that everyone can get hooked up at the end after the smoke clears. And the last ground campaign against remnant alien forces in central Africa has concluded, but Levinson discovers disturbing signs that the aliens on the ground may have made contact with allies out in space.

Around the end of Act 1, the film starts to run into a bit of genre confusion. Emmerich et al. must be aware of the film Aliens and how it succeeded in creating a franchise by maintaining the fictional universe of Alien but changing from horror to action and adopting a largely different structure. (In point of fact, they surely are aware of it due to some design work that shamelessly rips off Cameron’s 1986 film.) So what IDR is trying to do is shift the genre from its predecessor, which was basically a disaster movie, into a full on space opera.

As a disaster movie, all of the tragic events of the original Independence Day are the result of random happenstance—the aliens happened to attack us. Generally in these films, while minor antagonist characters dismiss the threat, giving the heroes someone to prevail against, most people do not deserve what happens to them. The fantastic events are a metaphor for impersonal disasters like hurricanes and tornadoes.

As a science fiction space opera, the events of IDR must be incited by a fatal mistake. Here, humanity, while now enlightened with respect to itself, fails to act with compassion and wisdom when confronting beings from space. The primary character who commits this error is President Lanford (Sela Ward), who is not a bad person but one motivated by fear. However, in the same scene, she tries to prevent Levinson from investigating something that seconds before she was convinced was a threat from space, because she wants him to show up for a Fourth of July ceremony. As per the space opera conventions, the antagonist must reject understanding out of fear and aggression. But as per the disaster movie conventions, the antagonist must reject understanding out of complacency and hubris. In failing to fully commit to its genre shift, IDR thereby mangles both plot and character. Unfortunately, such carelessness continues to inform the proceedings.

As a result of blowing it, humankind is once again subjected to the alien threat. An opportunity is missed here to show the result of all the 20 years’ progress we saw in Act 1. It’s established very strongly that these are the same aliens, biologically and politically, as the ones in the previous movie. So you’d think that they would turn up with a similar invasion force, and humankind would put up a far superior fight before ultimately being overwhelmed. Instead, they show up with entirely different craft, tactics, and even goals. There’s kind of an inspired bit where Earth’s new defenses have an alien-laser duel with the new mothership, but the sequence is over in seconds and the movie forces itself back into the disaster-movie mold of massive destruction that cannot be forestalled.

From here we get all the worst excesses of Emmerich’s style—weightless, meaningless, thoughtless, bloodless destruction. In a few minutes, hundreds of millions of people—and a grand total of one named cast member—lose their lives. Now, there is nothing inherently superior about the pyrotechnics and model work of the first film compared with using animation in this one. But the visual effects artistry is not present here—the editing and the direction present the smashing of one city INTO another city with complete banality. In Independence Day, death was preceded by dread and punctuated with horror. Here, David Levinson cracks a joke about landmarks as millions are obliterated before his eyes, a moment that the movie only gets away with because the audience doesn’t really buy into this at all. If such a one-liner had been put over the urban charnel houses of Independence Day, we would have been aghast.

From here on out, the human forces get dealt setbacks at the appropriate times called for by screenwriting logic, without any actual in-universe logic. In one scene, the aliens are ignoring us because their craft is too big to put a scratch on it. In another, they are launching an assassination attempt on a human politician. In another, they hatch a pointlessly elaborate supervillain scheme to deplete Earth’s military forces. In another, they leave a bunch of fighters unattended in unsecured territory. There are some weak justifications for their fluctuating competence about telepathy and a hive mind and such, but even this is self-defeating when a key part of the backstory is that remnants of the first invasion independently fought a ground war on Earth for ten years.

The alien modus operandi does have a certain logic to it—they need their ubership to suck out Earth’s iron/nickel core. While it’s unclear why any spacefaring civilization would particularly need this resource, it does suggest why they need a moon-sized craft and why they would bother to target inhabitable planets and make them uninhabitable—as Levinson points out, life as we know it would not survive the loss of the Earth’s protective magnetic field. However, this method of attack is completely incompatible with the piecemeal extermination of the first movie. Worse, the humans later obtain information that the aliens “harvest” all planets this way, so nothing the aliens did in Movie 1 actually advanced their alleged goals. Emmerich once again proves unable to make his aliens both inscrutable and defeatable without making them look like a bunch of boobs.

I find movies that almost hit the mark to be endlessly intriguing. There are so many cool ideas that are explored here. The idea of an alternate-history Earth. Hints of interstellar war and politics. An African warlord who projects brutality but is actually telepathically sensitive to the aliens. And Hemsworth’s character reminding us that literally everyone on Earth has lost someone, and most aren’t fortunate enough to be descended from surviving war heroes like Hiller and Whitmore. Finally, the fact that the movie is both made and set twenty years later adds weight to the story, in the same way as it does in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. This movie wouldn’t make any sense without the time gap, because civilization wouldn’t be rebuilt; if it had been made five years after the original, you’d either have aliens with nothing to do but make the debris bounce or you’d be sticking returning actors into old-age prosthetics.

By far the most appreciated element of the film is the relationship between Spiner’s Dr. Okun and Dr. Isaacs (John Storey). Okun was only in a couple scenes in the first film and was seemingly killed, while Isaacs actually had most of his scenes cut and was practically an extra. IDR exploits its connection to the first film to the fullest by bringing back the actors, revealing that these characters are lovers, and that Isaacs has been nursing Okun back to health for years. Okun emerges from his coma as the aliens return, due to his telepathic connection to them, and proceeds to swagger off with the movie, stealing every scene he’s in, while Isaacs plays the straight man. Unlike the perfunctory pretty-people romances, this connection feels deep and meaningful, and what’s more is not joked about or remarked upon by any other characters. The love of two old queer men for each other forms the emotional heart of this film. It’s 2016. Should this be a radical statement, in the context of a broad-demographic blockbuster? No. But is it? Sadly, yes, and I give it full credit for that.

It’s thoughtful elements like this that make the pervasive thoughtlessness of the film so galling. First of all, the fact Patricia Whitmore was recast is a crime. In the years since Independence Day, Mae Whitman, who played Whitmore’s daughter, has proven herself in comedy, action, and in starring roles. By all current accounts, Whitman was not asked to return, and the knowledge that she was almost certainly passed over for shallow and regressive reasons will forever cast a pall over Monroe’s fine performance as the character. Recasting Dylan is more understandable since Ross Bagley hasn’t maintained his Hollywood career, but unfortunately Usher doesn’t convince as the same character in the way that Monroe does.

The production also wastes the talents of Pullman, Goldblum, and Judd Hirsch. The former is given a “crazy” shtick, reducing one of our most charismatic actors to mugging and grasping his head in simulated pain. The latter two are trying about ten times harder than before to be funny and succeeding almost never. In Independence Day they were indispensable to the delicate tonal balance that film struck, while here they feel totally redundant. This isn’t a trivial concern, as by all rights Goldblum should be the main character. Instead the weak part that he’s given allows the films’ five interchangeable hotshot pilot characters to vie for the role (and still lose out to Okun).

Finally, despite only existing due to this ephemeral moment where a bunch of ‘90s kids like me are remembering how Independence Day made us feel twenty years ago, the movie doesn’t really bother to hit the nostalgia button. David Arnold’s pounding score is gone, replaced with…I’m actually not sure this movie had a score. The aliens almost feel like they were originally scripted as a whole other species. Some animators must have worked thousands of man-hours in order to make the alien fighters similar to the iconic crab-ship of the first, but somewhat worse in every way. Compare this to the cunning ways that The Force Awakens and Jurassic World used, manipulated, and invoked the imagery of their predecessors. We put up with the genericized predator of Jurassic World because the original Rex is going to tear it apart in the end. Deliberately making your iconic creatures more generic is self-defeating and asinine.

I want to see the crazy sequel to this movie where humans kick alien ass across the galaxy, but this movie didn’t earn it and probably won’t get it. By failing to understand that Independence Day was the result of a tight story, magnificent editing, and haunting imagery, the filmmakers accidentally made the argument that it’s not suited for expansion into a franchise. The only real hope is to transfer creative control from the people who made Independence Day to a younger director who loves Independence Day, a la Jurassic World. Emmerich’s futurist world building needs to be paired with thrills and pathos. Otherwise, there’s nowhere for the Independence Day universe left to go but quietly, into the night.

Independence Day: Resurgence is currently resurging in theaters.