Welcome to Angry Turtle!, a series featuring Deadshirt.net’s own Patrick Stinson and guest writer Andrew Tucker looking at the Gamera series, the films made by a rival studio to compete directly with Toho’s famous Godzilla series. The name comes from this charming video.

Patrick: Before we started in on this one, I told you Gamera vs. Gyaos was my favorite of the original 1965-1980 Gamera series. Did it hold up for you or disappoint?

Andrew: This movie was fantastic. I went into the original series excited because I had seen the ’90s Gamera series and loved it. I have to confess, it’s been a disappointing ride up until Gyaos, which is interesting given that the first ’90s Gamera movie revives a lot of this movie’s plot. But this movie is one that I would happily share as a perfect example of why Gamera deserves his own spot in the kaiju pantheon.

Patrick: We were talking about this the other day, how Gamera is the only kaiju outside of the usual Toho suspects (Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah) who has reached iconic status. The Simpsons tries to sneak in a kaiju gag every so often, but even so his use in the Simpsons episode “Thirty Minutes over Tokyo” is striking.

Andrew: You’ve got a pretty heavy showing of Toho’s major kaiju heroes in that shot, and then there’s Gamera. Although, I remember as a kid feeling like he belonged there. I grew up on Godzilla but didn’t see Gamera until I was in high school; nevertheless, I knew of him enough to feel comfortable seeing him in that lineup.

Patrick: Yeah, Gamera was not as reliably found as Godzilla on home video back then. My only exposure to these films was seeing trailers and Gamera vs. Guiron, which we will cover in a couple columns.

Andrew: I was lucky enough to find a box set of the Heisei (’90s) series at Suncoast. I remember thinking it was this special artifact that I would never find again, so I snatched it up.

Patrick: Whippersnapper! I bought those movies one at a time on order. The first film came with the box for the other two, which didn’t come out for months! But that’s another column!

Andrew: Gyaos! The iffy-ness of Gamera’s morality is now gone, and our giant turtle friend is in full-hero mode in this movie. We actually get to root for him, pity him, and see him build relationships, both with children and his adversaries.

Patrick: I love that Gyaos’s name is an onomatopoeia for its roar. In-story.

Andrew: This movie struck a really good balance. You have Gamera flying a child around on his back, but at the same time you’ve got Gyaos eating civilians and almost slicing Gamera’s hand off! This is what the Showa kaiju movies do best. It’s where you see these movies celebrating their own genre. It’s not camp, but it’s not gritty either.

Patrick: The Gamera Formula™ is starting to solidify here. Director Noriyuki Yuasa replaces baffling idiot child Toshio from Gamera the Giant Monster with slightly-too-competent-but-still-believable child Eiichi. While he is singled out for rescue by Gamera and consulted by the adult characters, he manages to be a wish-fulfillment character for the kids watching without completely hijacking the movie. You’ve also got the use of gore and dismemberment as a way to differentiate from Toho’s increasingly family-friendly Godzilla series.

Andrew: I’m not a huge fan of the Godzilla movies coming out during the first few Gamera years, so it’s interesting for me to see these movies develop using a lot of what made the early Godzilla movies so great, which is social commentary. At its heart, Gamera vs. Gyaos wrestles with Japan moving into an industrial, more progressive nation post-WWII.

Patrick: Yeah, so the monster plot is fit in around a conflict between villagers and developers for some unspoiled mountain land. I believe they literally want to build a bypass–shades of Arthur Dent. However because this is the ‘60s, this is presented as a pretty good thing, with Kojiro Hongo playing his second lead character in a row as a leader on the developer side. Eiichi is a villager, and his grandfather is the village headman who’s playing hard-to-get for a better deal. Interestingly enough, it’s not Man’s Arrogance that releases Gyaos from his volcano lair onto this area, but a random natural eruption.

Andrew: It was quite jarring to follow the characters in this movie. As formulaic as these movies have and will be, I found myself assuming the villagers were the down-trodden heroes, but the character development in the film concerns them. You see them grow in degrees from adversaries to helpless bystanders to passionate allies. One of the first interactions you see is the villagers ransacking the construction site only for Kojiro Hongo’s character, Foreman Shiro Tsutsumi, to peaceably lead his men in cleaning up the mess and getting back to work. Although, there does seem to be some tension in Tsutsumi’s boss forcing the men to work amid the volcanic activity.

Patrick: The movie can withstand a nuanced human plot because the real villain is the monster. It’s like “I voted for the other guy” in Independence Day. Speaking of which, let’s talk about that monster. Gyaos is a genius creation, with a simplicity that most of the other Gamera foes lack. He’s a bat/pterosaur thing who eats people and has a sonic beam that can slice through anything, even Gamera’s limbs. He’s viscerally dangerous in a way few other kaiju are, and it’s no accident whatsoever that Gyaos, uniquely, followed Gamera into the series reboot.

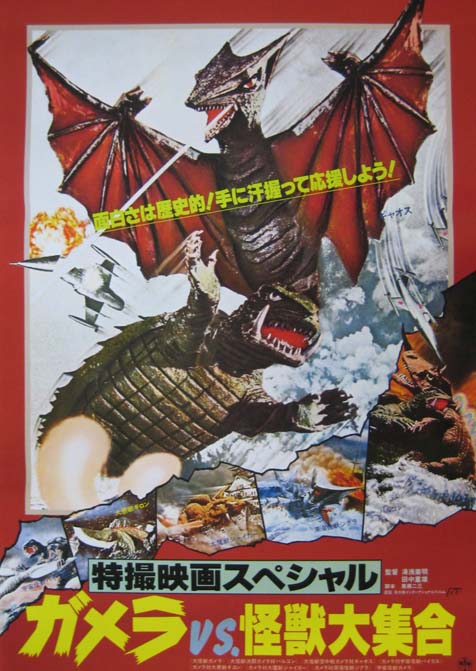

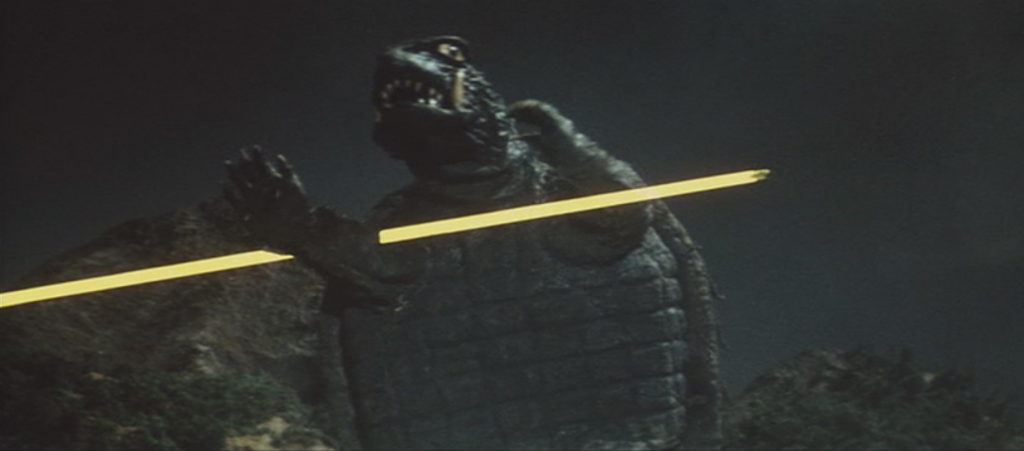

Andrew: Gyaos is one of the most dangerous and lethal kaiju that I can think of. He would give Toho’s grand-nemesis, King Ghidorah, a run for his money. I particularly enjoy that we see the human suffering caused by his beam attack. He slices a plane in half, and we see its passengers struggle before the plane blows up; if this were a Toho film, all we would see would be the exploding model. This movie wisely positions Gyaos with the most brutal scenes, while Gamera plays defense until the end. The hero/villain relationship is very clear in this movie, unlike in Gamera vs. Barugon. I was shocked when Gyaos sliced into Gamera’s hand! It’s also a nice touch that he’s nocturnal. This movie makes great use of archetypes such as the night, the volcano, and the sunrise. The only thing that disappointed me was the suit design. I don’t know if Daiei, the studio behind the film, didn’t have the budget Toho had, but the suits for Gamera’s nemeses are terrible when compared to those of Ghidorah, Anguirus, or Rodan (pictured below).

Patrick: Gyaos is a vampire: his wings are his cape, blood is his motif, and sunlight is his weakness. The stiffness of his suit is even worked into the story, with his dual-throat restricting his head movement, but being the source of his lethal beam. It’s…an attempt, at least, to deal with the fact that Daiei Studios just couldn’t make the monsters look as good as Toho did.

I do want to point out that while you say Gamera plays defense, he’s actually much more active and capable than the previous two outings. He arguably wins all three battles with the creature. There’s an unfortunate tendency to sideline Gamera after his first fight (we saw this in Barugon) that’s avoided here, and it firmly establishes what will become Gamera’s character going forward–a kaiju superhero, both capable and compassionate. Any tonal discrepancy with the previous two films is more than made up for by the strength and vision of the character that starts in the first twenty minutes of this film and continues into the present day.

Andrew: Absolutely. I see Gamera in this movie as being a constructive force, unlike his previous appearances. Everything he does is connected to some positive act, whether it be stopping Gyaos from destroying his surroundings or saving Eiichi or healing himself. In Barugon, Gamera just shows up to fight – here, he is a guardian monster. And, we get to see him do new things! I particularly enjoy how, when faced with the injury to his arm, Gamera goes inside his shell and rolls down a hill like a tire into Gyaos. You can see him thinking through strategies and decisions in a way that has been absent in the prior films. It’s very touching when he flies Eiichi to safety on his back and gently leans into a crane so Tsutsumi can grab him.

Patrick: At this point, the Godzilla scripts were probably just putting “Haruo Nakajima (Godzilla suit actor and choreographer) does something cool” as their stage direction. The Gamera movies clearly have every move written into the script, with some of them being explicitly referenced later. For instance, Gamera rescues Eiichi by debuting a non-spinning mode of flight. Eiichi is later asked about this, and it gives other characters the inspiration to spin Gyaos on a turntable and wreck his equilibrium so that the sunrise kills him. Gyaos’s relative reluctance to face Gamera’s flames in the same battle is also pointed out by the characters and used in their own strategy. It gives a different feel, less spontaneous and more deliberate, to the action. It is more like a comic-book battle, move versus countermove, than a wrestling match.

Andrew: My only issue comes in the plan to defeat Gyaos. They discover that Gyaos is nocturnal and afraid of flame, so they plan on killing him with the sunrise. They lure him to a platform with – disturbingly – the smell of human blood, and there they spin him around. I felt like a monster as competent as Gyaos would have either flown away or just stepped off the platform. That aside, I felt each section of this movie flowed into the next quite naturally and excitingly.

Patrick: Yeah, pacing is not this movie’s problem. Appropriately, a major shift in emphasis comes in the second act when Gyaos first invades a major city. Kaiju movies often have to transition a small, low-stakes story into a big one while not totally abandoning the first set of characters, and this one does the job as well as any. Setting Gyaos’s lair in a defined location keeps the village characters relevant in a way that Gamera the Giant Monster does not manage.

Andrew: I find that the strongest kaiju movies have monster drama acting as a backdrop to human drama, and this is one of the strongest examples of that. I actually found myself missing the villager plot amidst the Gyaos conflict just in time for it to reappear. The villagers decide to work with the construction company only to have their elder, Eiichi’s grandfather, continue to hold out. The monster plot is only allowed to progress if the human one does, and that makes me engaged in both.

Patrick: Godzilla screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa pioneered an unconventional structure in the ’50s-’70s Showa era where the human problems that are set up by the first act happen to be solved or made irrelevant by the actions of the monsters in the third act. The humans are ultimately powerless to interfere with the kaiju. This screenplay is a bit more conventional in that human characters do most of the legwork in defeating Gyaos. But in this way, a partnership motif between human military and police forces and Gamera is set up, a motif that will continue to pay off in future films. Again, Gamera steps into a superhero role.

Andrew: Sekizawa’s approach works very well when the kaiju are forces of nature or societal ills personified. For example, Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla (2014) works well because the MUTO represent man’s technological mistakes while Godzilla represents nature’s power. The human’s must suffer the consequences of their actions via MUTO and must also surrender to nature’s fury via Godzilla. With Gamera, and indeed the 70’s era of Godzilla, these kaiju are superheros and supervillains, with the human as critical sidekicks. Side note, it has just occurred to me that Edwards snuck a little kid with a baseball cap into his Godzilla movie (pictured below)! That man is a true Showa disciple.

Patrick: Oh man. Well, yet another example of Gamera’s influence on the genre.

In our next installment, Gamera vs. Viras, we will see the series yield to temptation both from the Godzilla series and from the contemporary comics of the Silver Age…