For some people, watching a movie set in or around Hollywood is just too much inside baseball. But for the diehards, exploring the world of filmmaking has birthed some of the medium’s greatest triumphs. Over the next few months, our very own Dominic Griffin is going to revisit the gems of Movies on Movies…

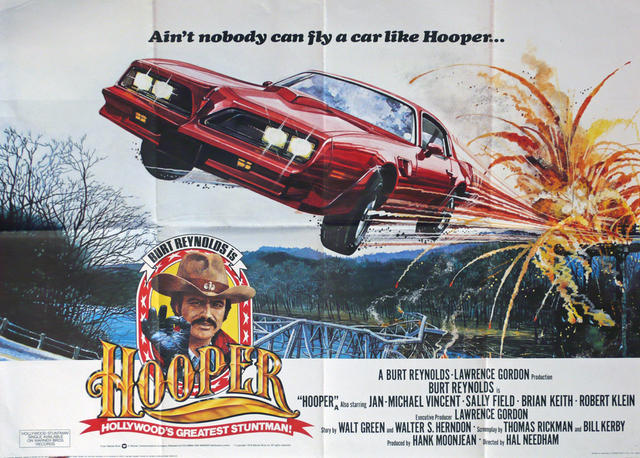

While many movies set in the world behind Hollywood’s cameras tend to focus on the star of a picture, its writer or director, Hal Needham’s unsung Hooper chooses to frame its narrative around a stunt man. The stunt man, really. Where Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man was a schizophrenic character piece using the manic minutiae of a film set to explore obsession and identity, Hooper is a loving ode to the beer swilling mavericks who made our favorite action scenes possible before the prevalence of CGI. The film takes a crucial, faceless cog in the movie making machine and lets a screen icon pay them thrilling homage.

Burt Reynolds is in rare form here as Sonny Hooper, the kind of man’s man protagonist he’s spent his lengthy career inhabiting. Hooper’s doubling for Adam West (in a sly little performance as himself) on an obviously shitty spy thriller whose artistic merit fails to balance out with the danger its gags place him in. He clashes with director Roger Deal (Robert Klein in a sour-faced pastiche of Peter Bogdanovich), who embodies everything about Hollywood that makes regular joes uninterested in the intricacies of the inner workings. Deal is petulant, selfish and short-sighted where Hooper is warm, virile, and principally concerned with the well-being of his friends. But he’s not without his faults.

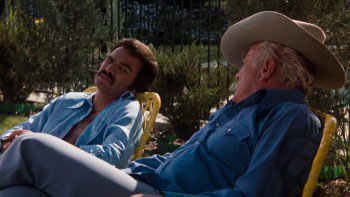

Everything that makes Hooper such a great stunt man makes him a questionable lover. His girlfriend Gwen (Sally Field) is perpetually left in limbo about their future together, both because Hooper refuses to get married (again) and because of his propensity for life threatening gags on set. Gwen’s father Jocko (Brian Keith) was a stunt man, too, and he appears throughout the film like a ghost from Christmas future, presaging the kind of existence Hooper may doom himself to if he stays on this current track. For every death-defying feat Hooper accomplishes on set, there’s an equally disquieting moment following it where we see the toll it’s taken. When he tries to talk himself out of seeing a doctor, he laments that his X-rays look like a map of California. Once Hooper finally does go to see him, the doctor is reminded that most of his medical expertise comes from years of putting Hooper back together, a perpetual humpty dumpty machine masquerading as a man.

It takes seeing Jocko in a hospital bed, lamenting a lifetime of bad decisions, to make Hooper see the light. Jocko reminds him that no movie is worth a man’s life. That sentiment sets Hooper apart from similar films set in Hollywood. So often, those stories center around a tortured artist’s soul and place a premium on intellect. There’s that jaundiced consensus that the director is the sole creator of the film and everyone else is merely along for the ride. Hooper flips that paradigm, focusing instead on the blood, sweat and tears of the men actually on the frontlines of make believe.

Deal embodies everything that’s wrong with the auteur theory, with his narrow-minded views on storytelling and artistic collaboration. Just as Hooper is ready to hang up his boots, there’s one last stunt he has to do for Deal that involves jumping a rocket car over a demolished bridge twice as far as the world record. Hooper initially refuses, but he realizes that Deal will just force rookie stunt man Ski (Jan-Michael Vincent) to perform the task alone. Deal doesn’t care that’s it’s a two-man job and that Ski could die. He just wants to get his shot.

The camaraderie between Hooper and Ski gives the back half of this film a lot of heart. Their relationship seems adversarial at the start, with the inherent generational divide of a veteran and a newcomer splitting hairs between their personal codes and practices. But the two men find a kinship that’s charming. That closeness is what drives Hooper to agree to do the stunt. Also the hefty price tag he’s charging should let him spend the rest of his life not driving cars into walls or hopping long distances on motorcycles.

The film’s comically extravagant final set piece is a towering monument to throwback action flick aesthetics. Hooper and Ski drive a muscle car through a sprawling Rube Goldberg device of explosions and crumbling infrastructure while Deal films from above in a helicopter. The marathon concludes with the impossible jump, and it’s a testament to the film that this moment is played with a shrewd balance of cathartic bliss and trepidation. As a consumer of film product, you want so desperately to see the jump, because that’s what everything has been building to, but after having spent the run time with Hooper and knowing how damaging even its success could be to his body, part of you wants him to say fuck it and peel off in the opposite direction.

This is a movie, though, and not the kind that’s going to deny you the secondhand thrill of Burt Reynolds leaping a gorge in a rocket car. On one hand, following through with the stunt seems antithetical to the film’s message of not placing artifice before real life, but it nails the sense of teamwork that it takes to make a movie special. When Hooper and Ski come out on the other side and share a knowing glance, it counteracts every shifty side eye Deal dished out from the perch of his director’s chair. Hooper reminds you it takes a village to raise a flick.

Check back in the coming weeks for the next installment of Movies on Movies…